The first torpedo slammed into the hull of the aircraft carrier just before dinner.

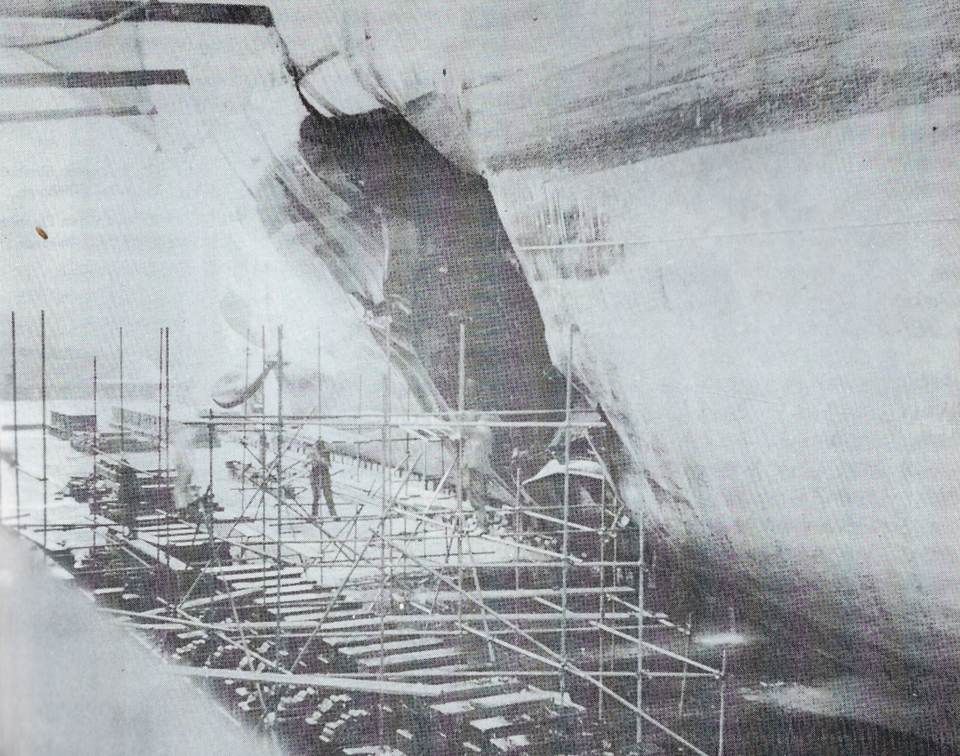

The blast opened a gaping 32-foot wide hole in the hull of the ship below the waterline, triggering the action alarm.

Below deck, the explosion tore through the galley and spirit room, where the crew had lined up to receive their rum rations. Nearby, men were thrown from their hammocks and bunks.

One stoker was moving oil to the front of the ship when the torpedo knocked out the lights; he was forced to grope through 50 feet of darkness to the nearest escape hatch, according to a Royal Canadian Navy dispatch.

Another petty officer from Toronto was in a pistol testing room near the mess when the blast exploded through the room, leaving it in darkness. Water rushed about his legs and swept him up to the next deck.

“He dived under water, swam through the doorway and managed to make his escape through the hatch he had originally endeavoured to get away by,” wrote Lieut. Commander Walter Gilhooly in a statement from Naval Headquarters nearly a year later.

The first order came down from Canadian Captain Horatio Nelson Lay: “Prepare to abandon ship.”

It had been seven minutes since the first torpedo hit, and rafts were being lowered to the waterline.

Edward Hart of Coquitlam was on the flight deck when, “in one horrifying moment,” he looked up and saw a second torpedo intended to finish off the Nabob detonate against the hull of a nearby destroyer, killing 40.

“There were bodies flying straight up into the air,” remembers Hart.

HUNTERS BECOME THE HUNTED

Born in Saskatchewan, Hart moved west at a young age, settling with his family in Mission, B.C.. But as the war raged on, the young man — too young to join the services — lied about his age and joined the Royal Canadian Navy.

Hart was assigned to what would go down in history as the country’s first Canadian-crewed aircraft carrier, the H.M.S. Nabob, purchased from the US Navy and retrofitted to Royal Navy standards at the Burrard Dry Dock in Vancouver.

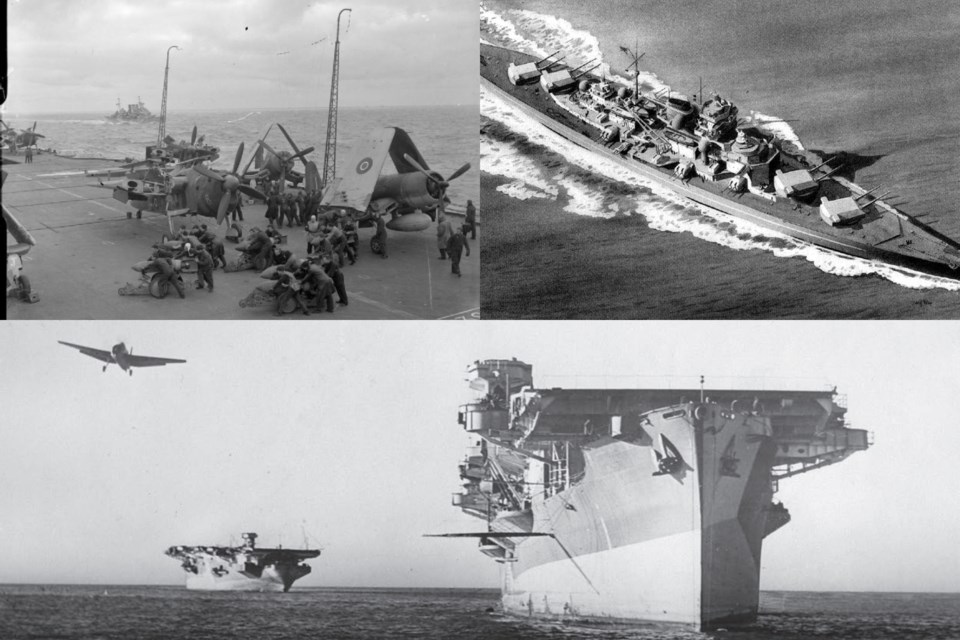

Launched March 9, 1943, Hart sailed out of English Bay with a complement of what would later amount to 840 crew and officers. On course for Europe, the ship stopped in San Francisco to pick up a squadron of Grumman Avenger torpedo bombers and passed through the Panama Canal before collecting another deck load of P-51 Mustang fighter planes in New York.

Soon, the Nabob was attached to an Allied carrier group, part of the British Home Fleet and on a mission to root out the German navy in occupied Norway.

On Aug. 22, 1944, the fleet approached Kaafjord, 500 kilometres north of the Arctic Circle. Its target, the Tirpitz, a hulking 800-foot Bismarck-Class battleship anchored at the head of the fiord.

By the afternoon, the attack against the German battleship was underway. Overhead, Grumann Wildcat fighters flew combat air patrol as the ship’s Avenger bombers joined the main force, dropping mines in an attempt to sink the battleship. Just after 5 p.m., the Nabob was refuelling three nearby ships.

Little did the crew know, German U-boat U-354 had crept up off her starboard side.

A NARROW ESCAPE

The carnage from the first torpedo could have been much worse.

“It’s ironic, 15 minutes later there would have been over 400 guys right where we were hit in the mess deck,” Nabob crew member Len Love told The Province in 1994, on the 50th anniversary of the attack.

Sonar operators tracked the approach of a third torpedo. This time, it missed.

Below decks, damage control parties raced to close hatches and doors to seal off the incoming sea. With the aft of the ship now 16 feet below water, crew members cut away and tossed the five-inch guns into the sea, together with whatever bombs and mines couldn’t be moved towards the bow.

Inside, wounded were carried away from the scene of the explosion on stretchers and into the darkness of the ship’s canteen. Ventilators and fans kicked in to clear the engine room of smoke.

The crew was gaining the upper hand and it was soon determined that despite the massive hole in the hull, there was no immediate danger of the ship going down.

Hart, along with the rest of the all-Canadian aircraft handling crew, secured the torpedo bombers and fighters on the flight deck.

Three Royal Navy destroyer escorts formed a screen around the listing ship, and soon the Canadian Fleet class destroyers, H.M.C.S. Algonquin and H.M.S. Vigilant were on their way to help.

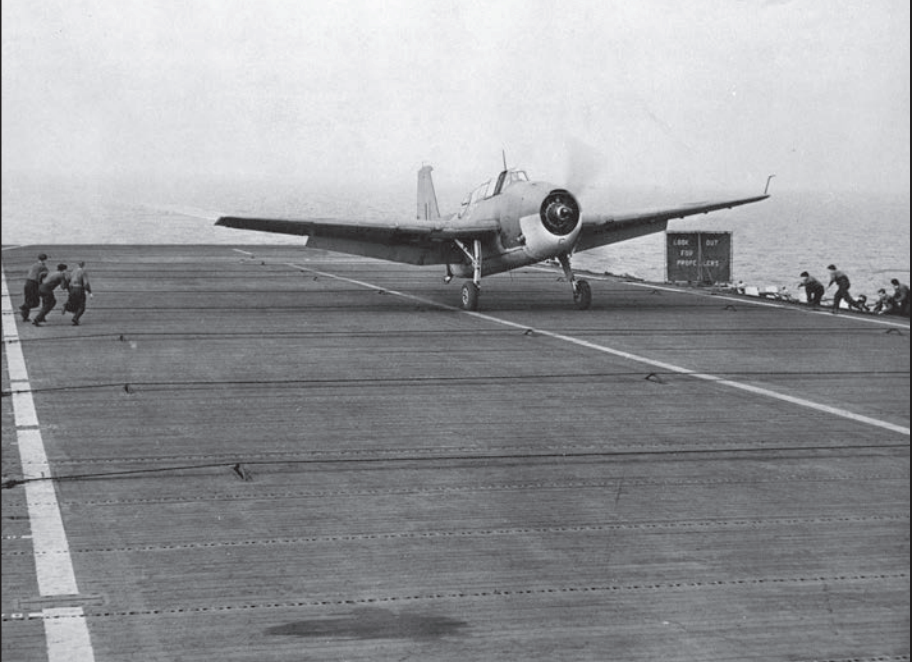

At 3 a.m., two Avenger bombers launched from the sloping deck of the Nabob tasked with driving off a trailing U-boat as the ship steamed the 1,100 miles from Norway to the sheltered Scottish waters of Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

WAR’S END

All told, 21 crew members died aboard the Nabob.

The German attackers fared worse. A day later, aircraft from another ship sank U-354, killing all 51 crew members.

And while the Canadian-crewed ship ended its naval service following the torpedo attack, Coquitlam’s Hart would go on to serve aboard the notorious frigate H.M.C.S Swansea, which during the Battle of the Atlantic, would sink four U-boats, more than any Canadian ship.

After serving 12 months at sea across 13 posts, Hart was demobilized in the fall of 1945. He returned home, settling in Coquitlam and serving as an officer in the Vancouver Police Department until his retirement.

Now 97-years-old, Hart looks back on that day as a turning point in his young life.

“I knew I would never be the same afterwards,” he said.

The Coquitlam man has struggled to share his experiences during the war. His daughter, Carol-Ann Hart, said that’s only recently started to change.

“Over the years, he’s been more willing to talk about it. He’s proud of what he did,” the younger Hart told the Tri-City News. “But when I was a kid, he kept it close to his chest.”

Never one for ceremonies, Hart and his family usually mark Nov. 11 by pinning poppies to their chests and going out for a nice lunch — often at the Boathouse in Port Moody.

But this year, Hart’s wife is in hospital and the family tradition is on hold.

Still, Carol-Ann has found her own way to remember. As a citizenship judge, she presides over ceremonies welcoming new Canadians as they swear allegiance to the country and its values. In one breath, her speech calls attention to the country’s deep Indigenous roots; in another, she recalls her father’s story and what he and his crew endured in the Arctic waters off Norway 76 years ago.

“I feel so incredibly lucky,” she said.