Time is running out for British Columbians to have their say on the future of the province’s old-growth forests.

The feedback process, which ends Friday, Jan. 31 at 4 p.m., is the result of an independent two-person panel, convened by the provincial government to consult the public on the ecological, economic and cultural importance of British Columbia's oldest trees.

The public is invited to opine on why they value old-growth forests, how they’re managed now, what’s wrong with the current approach and how it could be more effectively managed in the future.

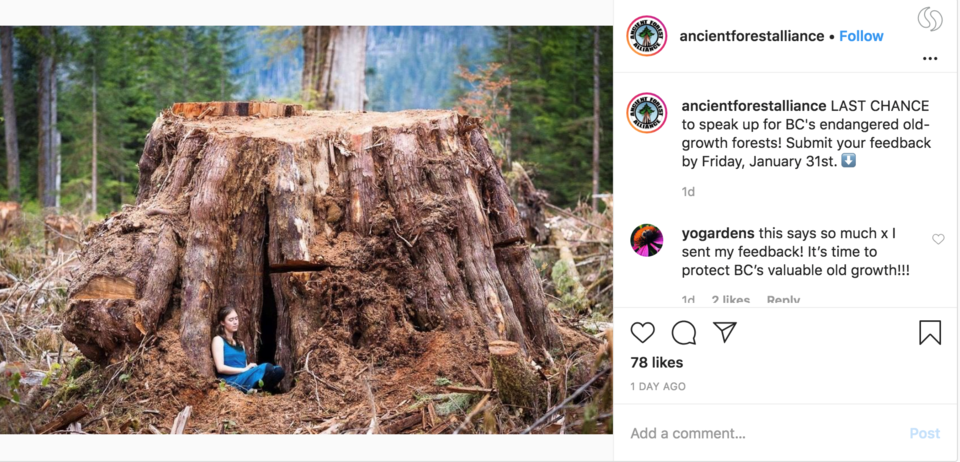

Old-growth forests, which once made up vast swaths of the province’s land and provided thriving ecosystems for a variety of species, have been decimated over the last 150 years. Across B.C., 5.5 million hectares of old-growth forest — an area approximately the size of Croatia — have been reduced to 26% of the original coverage, according to data gathered by the Ancient Rainforest Alliance.

Port Moody resident Andrea Innes works for the Ancient Rainforest Alliance, a group that is advocating to develop a “legislated, science-based plan” for protecting old-growth forests in the same ecosystem-based approach that has already been taken in the Great Bear Rainforest.

“This is a very rare opportunity that we probably won’t see again for a long time,” Innes told The Tri-City News.

The group is also calling on the government to provide resources for First Nations’ sustainable economic diversification and fund the creation of Indigenous protected areas; create a province-wide lands acquisition fund to buy and protect old-growth sitting on private lands; and end the logging of B.C.’s most endangered old-growth forests.

The feedback process is open to everyone, whether Indigenous, a business owner, tourism operator or recreationalist.

“I’m hoping that the panel can recognize and convey to the government just how serious this is,” said Innes. “So far, the government has been unable to recognize the facts.”

Over the long term — decades or centuries into the future — old-growth forests provide what Innes describes as “ecosystem services,” meaning the sequestering of carbon from the air, stabilizing slopes to prevent flooding and landslides, as well as acting as an anchor for a watershed’s ability to send clean water downriver.

Much of the old-growth logging that occurs in B.C. these days occurs on Vancouver Island.

In the lower reaches of the Tri-Cities' watersheds, massive old stumps hint at an ancient forest that once was. Many of the old-growth stands here were logged between the 1960s and mid-’90s.

In harder to reach areas, like the upper Coquitlam watershed, old-growth trees were on steep slopes far enough from the mills to evade logging.

Today, 90% of the upper Coquitlam watershed is considered old-growth, according to Jesse Montgomery, a manager for Metro Vancouver’s Watershed and Environmental Management department.

At 20,000 hectares — or 50 Stanley Parks, as Montgomery puts it — the upper Coquitlam watershed provides one third of the water for Metro Vancouver’s 2.5 million residents. That’s made possible by a 999-year lease, signed into creation as the Greater Vancouver Water District back in 1942.

“That was primarily done to ensure water supply,” said Montgomery, “We’re in an incredible fortunate position to have these large forested landscapes.”

Coquitlam, according to Montgomery, has some of the tallest Douglas fir trees in the world.

“It is a very different situation here than on Vancouver Island,” he said. “[Here] the threat of deforestation is not front of mind.”