Sitka has brown, bulbous eyes, slippery skin and breath that makes you want to pass the next time you’re out for sushi.

At roughly 230 kg (500 lb.), she’s the biggest of the four Steller sea lions housed at the Marine Mammal Research Station floating off the end of Reed Point Marina in Port Moody, and together with the other three pinniped residents, is among the most highly trained sea lions in the world.

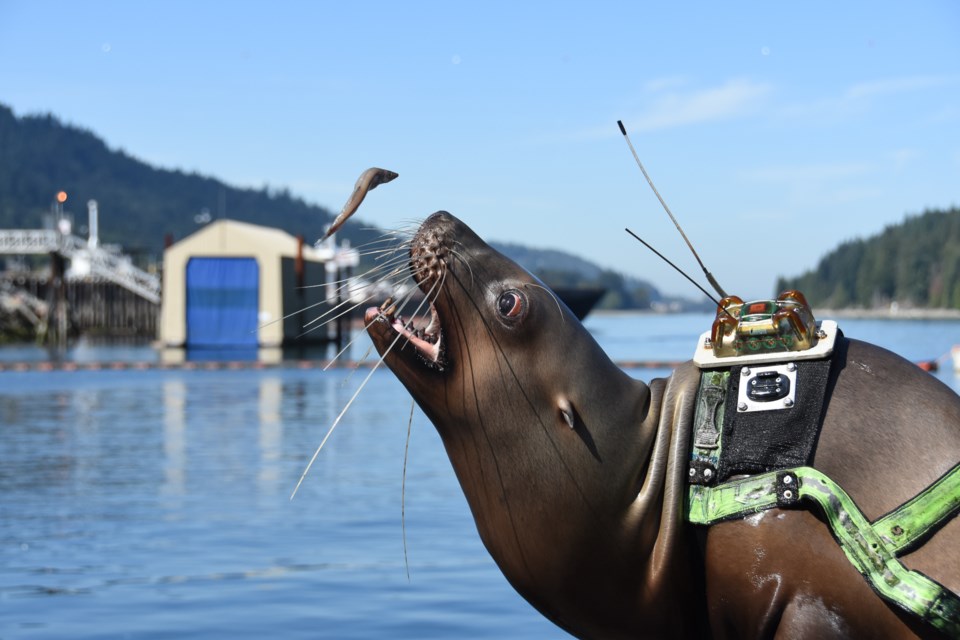

As part of her morning routine, trainer Nigel Waller coaxes Sitka out of the open-water pens with a bucket of squid and herring. She obliges, hurling herself across the dock and onto a scale before slipping on a neon-green reflective vest fitted with a GPS and radio tracker “just in case.”

The boat-side swim, the battery of handstands, diving, jumping — even sticking out her tongue — are all part of a well-honed routine to prime the animals for controlled open-water experiments found nowhere else on Earth.

The rigorous training lets the team push into the deep waters of Indian Arm, where it can test the nuances and limits of the animals’ feeding, diving and breathing patterns in their natural surroundings. In many ways, the research station forms the missing link between observation in the wild and experiment in captivity.

It has guided conservation efforts as far away as Alaska, and as the scientists look to the future, they hope to use the Port Moody facility to gauge the effects of climate change, pollution and dwindling fish stocks closer to home.

Now, at this critical moment, funding for the 16-year-old facility has slipped and its continued existence is in jeopardy.

ON THE ROCKS

Physiologically, Steller sea lions are the bears of the sea. They’re carnivores, somewhat choosey, but feeding on whatever catches their interest. They live in two big populations, one in B.C., and a second historically larger group stretching from eastern Japan through the Aleutian archipelago and down the Alaskan coast.

By the early 1990s, both populations plummeted. While it was clear overfishing and culls had affected their once vast numbers, scientists struggled to understand exactly how the world’s largest population of the world’s largest sea lion continued to dwindle.

In 2003, the situation was desperate, so marine biologists from UBC teamed up with the Vancouver Aquarium to launch what David Rosen calls a one-of-a-kind research facility, a testing ground to document both the choices sea lions make in the wild and how the limits of their unique biology affect survival.

Since the Vietnam War, the U.S. navy had run secret training programs with the Steller’s smaller Californian cousins — deploying them to protect navy assets from swimmer attacks and spot sea mines — but few had tried to train the larger, seemingly more ferocious Steller in the service of conservation.

“We’re the link between laboratory studies in an aquarium and studies in the wild,” said Rosen. “We’re the only people getting those types of answers.”

Over the last 16 years, the body of scientific research coming out of Port Moody has been instrumental in shaping the species recovery plan for endangered Steller sea lions in Alaska.

But where money was once plentiful, secured funding dries up at the end of this year. From there, survival is month-to-month.

Money occasionally trickles in from unlikely sources: The Disney-backed series Siren films at the floating laboratory, a drama throwing marine biologists, locals and predatory mermaids into vicious conflict as the toothy creatures “return to reclaim their right to the ocean.”

A brewer in northern California also kicks in some money, pledging a portion of the proceeds of its Steller IPA.

“I guess it's no different than trying to keep the family farm going. You go right to the bitter end, and do what you can,” said director Andrew Trites.

At thousands of dollars a year to feed single sea lion, operational costs are piling up just as Canadian Pacific Railway prepares to begin construction on a $31-million track expansion project adjacent to the Reed Point facility.

CP Rail’s project permit application for the Cascade Capacity Expansion Project, as it’s known, is vague on direct effects to the research facility, and staff are still trying to understand how the extension of the rail embankment will affect the floating docks 25 metres away. Construction is slated to begin Nov. 1 and, according to the project’s permit application, strong, low-frequency sounds will accompany the work day and night, seven days a week for two months.

“These animals are sensitive," Rosen said. "In the past, a company was testing sonar in the waters near Port Moody. The sea lions were visibly disturbed by the sounds travelling through the water."

In one scenario, CP told Trites the company would need to detach the facility and float it to another location so the rail company could bring in a barge to dump fill along the shoreline. The Tri-City News reached out to CP but did not receive a comment and was instead directed back to official documents.

“You’re moving a large facility. You never know what’s going to happen,” said Rosen. “This is crunch time.”

BAD TIMING

The need for more open-water research has never been stronger, according to the facility’s proponents. While in the past, the research station has helped sketch out a map for conservation in Alaska, today, the Steller sea lion population in B.C. continues to grow and some suspect its relative abundance may be affecting chinook salmon stocks, the key food source for endangered southern resident killer whales.

But it’s not just an increase in Steller sea lions that’s to blame.

Warming waterways and seas, along with habitat destruction, are also squeezing the already decimated salmon populations up and down the coast. The federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans is predicting this to be one of the worst years for B.C. salmon on record and, in a recent report, noted climate change is almost certainly a major factor.

Zoom in to the waterways of the Tri-Cities and local streamkeepers have already seen major die-offs this year at Hoy Creek in Coquitlam and Noons Creek in Port Moody. Pollutants, like climate change and years of over-fishing, can quickly throw the marine food chain out of whack.

“With development comes pollution and a change in ocean conditions,” said Rosen. “The effects on the waters around Port Moody are really amplified because of the shallow water.”

Beyond seal lions, the experience and location of the research station place it in the perfect position to understand this critical ecological moment, said Rosen. Locally, that means measuring the impacts of development — including industrial pollutants, boat traffic and how increased human populations can affect water quality — on Harbour seals, salmon, and increasingly, transient orcas.

“We’d like to start as soon as possible,” said Rosen. “We need this open-ocean laboratory in order to be able to answer those types of questions.”

Should it close, the institutional knowledge and experience built up over the last 16 years is something Rosen said will be near impossible to get back.

“You can't mothball it and then hope to start it up again when you get funding. Once this shuts down, you know, it's gone. The equipment is gone, the people are gone, the animals are going to be moved somewhere else,” Rosen said. “Once it goes, it's gone.”