A massive freshwater marsh on the edge of wilderness is approaching a new milestone on its way to becoming one of Metro Vancouver’s biggest parks.

The Widgeon Marsh reserve is currently shut off to the public, and only Metro staff, tenants, neighbours and researchers holding special permits can access the environmentally sensitive site — a swath of bogs, forest, grasses and waterways that make up part of the largest freshwater marsh in southwest B.C.

Metro Vancouver started buying chunks of land along the Pitt River around Widgeon Creek back in 1992. After 26 years biding their time, the Metro Vancouver parks committee is finally moving forward with its plans to open up the site to the public, one which is expected to see the same 150,000 visitors a year that Minnekhada park gets.

“It’s always been the intention of opening these lands. It’s just taken a while to get here,” said Metro park planner Deanne Manzer.

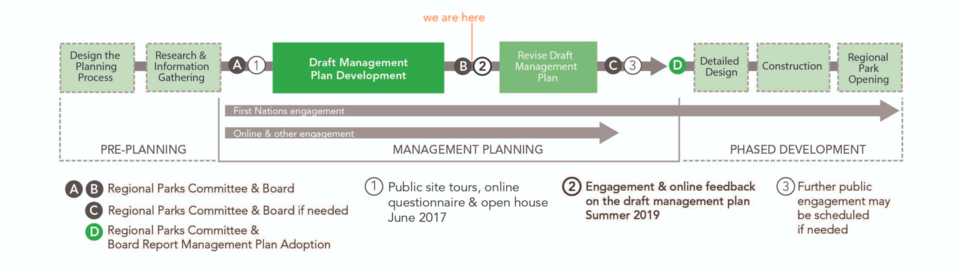

This summer, staff have held several in-person public consultations across the Tri-Cities, including at the Minnekhada trail head and Coquitlam’s Canada Day celebrations, among others. It’s all part of the second round of consultations, the results of which will be made public in the fall after everyone’s feedback is digested.

From there, Manzer said park planners will look at how they should change the draft blueprint before they take the final plan to the park committee for consideration. Once adopted, the plan would proceed to a year-long detailed design phase with a budget of $500,000. Another $6 million has been earmarked for the initial development of the park in 2021 and 2022 when basic amenities like parking, trails and pit toilets will be built.

For those who didn’t make it to the face-to-face public consultation but still want to have their voices heard, Metro Vancouver is conducting an online public survey until Wednesday, July 31.

“We encourage people to review our part planning that we have done for the area,” said Merkins. “[People] can let us know if we miss anything. If we've got something wrong, let us know.”

Beyond the general public, several other groups have been consulted along the way, including the Katzie and Kwikwetlem First Nations, the city of Coquitlam and environmental groups like the Burke Mountain Naturalists.

Victoria Otton, an environmental toxicologist and active member of the Burke Mountain Naturalists has mixed feelings about the turning the reserve into a public park.

“In an ideal world, of course, the Burke Mountain Naturalists would like things just to remain the way they are, and only us and a few other people can go in there and, you know, maintain our bird nest boxes and monitor bats — do all this volunteer stewardship,” Otton told The Tri-City News.

But after attending the in-person consultations, Otton says that Metro Van park planners have been paying close attention to what people have been saying during the consultation process.

“The top priorities are wildlife and habitat protection and keeping it as a wilderness experience for people,” said Otton.

The current draft plan bans domestic animals and motorized activities in the park; only passive recreation like paddling, cycling and hiking, or the pursuits of a naturalist like birdwatching and botanizing will be permitted.

The human footprint will also be contained. Only 6% of the park’s area will be open to visitors. According to an April 2019 draft plan, much of the area hived off for humans will be built on previously disturbed land: old log and gravel sorting sites, an abandoned meadow estate, and several houses left over from the limited homesteading that occurred there in the early 1900s. Even the main trail corridor will run along an old logging road that BC Parks now uses to access a paddle-in campground in Pinecone Burke Provincial Park.

Metro Vancouver parks continues to collect data inside the Widgeon Marsh. Markus Merkins, Metro’s wildlife specialist for the area, says his team set up 14 cameras in various areas of the reserve to monitor the range and behaviour of the animals, especially on land that planners believe could be opened up to humans in the future.

“[We’re] determining where we can establish areas where people can congregate without impacting the wildlife to a great extent, and also remaining safe from any kind of even wildlife conflict situation,” said Merkins.

For the most part, Merkins says they have seen animals typical for land at the edge of wilderness. That means fauna like wild cats, snowshoe hares, spotted skunks and Pacific jumping mice. As expected, black bears frequent the reserve for the seasonal wild berries and young grasses, though there are not nearly as many as have been spotted in nearby Minnekhada Park where large swaths of blueberry farms sustain a larger concentration of bruins. (In one unlikely find, the cameras at Widgeon Marsh even spotted a Grey wolf, something nobody thought existed that far south.)

Transforming the land around Widgeon Marsh into a park will allow Metro parks to control access to these sensitive areas, according to Merksins.

“If we just leave it open for people to use at their own whim, all sorts of activities may occur in those landscapes,” he said.

Of course, striking a balance between visitor areas and land reserved for wildlife is predicated on the idea that people will observe the rules, something that’s become increasingly difficult in easily accessed parks like Joffre Lakes, where bumper-to-bumper traffic has led some to blame an Instagram generation only concerned with getting the perfect shot.

Merkins concedes that social media these days certainly make park management challenging, but he also says shutting out people inexperienced with the outdoors is not the way to go. Instead, Widgeon regional park is a chance to inspire people with something more tangible.

Part of the draft plan looks to restore old settlement sites and some stream habitats that have been damned by weirs or damaged by logging roads in the past.

“[It’s] an opportunity to see this road to recovery, and how nature is rebounding from past resource extraction or whatever caused that damage,” he said, adding the size and bottlenecked access of the park means visitors will have to work hard to get to its upper reaches.

Otton, for her part, says she is cautiously optimistic. With the metro area’s expanding population, she understands why the park is finally going forward.

“I don’t think we can stop this one. People pay their taxes for parks. And if you’re not allowed in there, I can understand that people would be upset,” she said.

On the other hand, Otton and the rest of the Burke Mountain Naturalists will continue their volunteer stewardship in the park, though they will have to say goodby to the 150 to 200 swallow boxes they maintain there. It’s a sacrifice Otto says the naturalists are ready to make.

“The plan for the park is really to revert it to nature,” she said.

“That’s all right with us.”

— With files from Janis Cleugh