How have you been affected by the coronavirus outbreak? We want to hear your questions, stories and concerns. Here's how you can get in touch?

Outside a retrofitted walk-in clinic, parked vehicles surround the block — nurses, firefighters and others thought to be exposed to COVID-19 or linked with an outbreak wait for masked aids to escort them into an exam room.

On a bench in the hallway, a single masked patient waits to be admitted. Through two doors, Dr. Ali Okhowat of Coquitlam, the clinic’s physician lead, slides open a drawer inside a tiny exam room. Inside, sealed nasal-pharyngeal swab kits are scattered in two piles: blue for adults, red for children.

“The loads here are just… We can't keep up,” Dr. Okhowat said from behind several layers of personal protective equipment. “Now we're finding a lot of [gastrointestinal] symptoms are coming back, like diarrhea, for example, coming back as COVID-positive.”

The seven-day-a-week testing centre, across the street from Royal Columbian Hospital, has become an important facility for those exhibiting symptoms of the novel coronavirus, and a focal point of a new virtual triage system that has been rolled out across Coquitlam, Port Coquitlam, Port Moody and New Westminster.

The clinic opened March 16 and, within the first week, the family physician said there was a massive surge of people looking to get tested. By March 29, nearly 500 patients had walked through the clinic doors, although the Fraser Northwest Division of Family Practice Society (FNWD), which leads the effort, is forbidden to disclose how many have tested positive for the coronavirus.

Following provincial mandates, the clinic targets its testing to frontline medical workers and first responders. Outside of those deemed “essential,” doctors there can also test high-risk individuals such as pregnant women, care home residents or those linked to an active transmission chain or outbreak cluster.

“[Frontline workers] are terrified to be a vector,” said Dr. Okhowat. “[We’re] just trying to ensure first responders and frontline health care workers aren’t transmitting the virus among themselves.”

But while the clinic is restricted in who it tests for COVID-19, it has also opened up its doors to the public in other, more experimental ways.

By early March, clinics and family physicians across the Tri-Cities were struggling to manage a flood of patients exhibiting COVID-19-like symptoms, even as the supply of personal protective equipment — masks, surgical gowns, gloves and plastic face shields — ran dry. To protect their staff, many family physicians and walk-in clinics made the agonizing decision to close their doors.

“There were a lot of doctors and nurses testing people without equipment, going on leave because of exposure,” said Kristan Ash, the executive director of FNWD. “They put themselves at risk. And that’s horrible.”

At the same time, people are desperate, Ash added.

“People are stealing from hospitals. We’ve had people walking into doctors officers yelling and screaming for masks. A lady stole hand sanitizer from a clinic the other day, pumping it into a plastic bag,” she said. “I stood there and I looked at her and said to myself, ‘Do I stop her? But if you’re that bold and that desperate…”

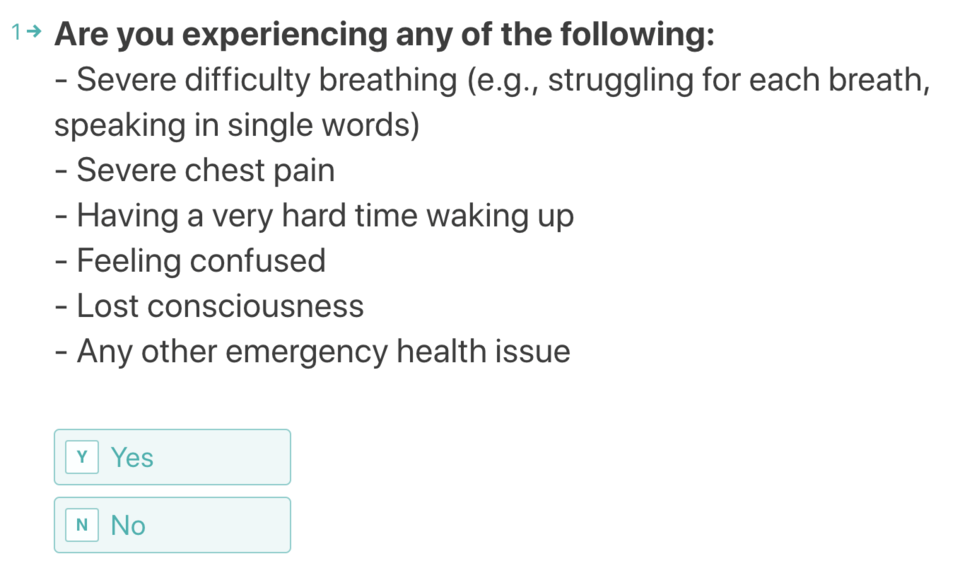

Into that melee stepped Dr. Okhowat, approaching Ash with his open-source COVID-19 self-assessment tool and a bold proposal to virtually triage patients.

“It’s unprecedented. For the last few years, it has been frowned upon,” said Ash. “The idea that you need to touch a patient to diagnose them has shifted in a week.”

But for Dr. Okhowat, injecting technology into medicine has been his life’s work. He spent years leading innovation projects with the World Health Organization across the Middle East. Since returning to Canada since the pandemic came home, Okhowat fields twice-daily calls from WHO colleagues in China, Europe and South America, helping them roll out a self-assessment tool so no one has to “reinvent the wheel.”

As cases started ramping up in the Lower Mainland, Dr. Okhowat's virtual tool opened up a lifeline between patient and the medical system, allowing anyone in the Tri-Cities access to a virtual consultation with a local doctor within minutes.

From there, a doctor can refer patients to a face-to-face check-up with one of the dozens of Tri-City doctors volunteering at the New West clinic.

FNWD’s new virtual triaging system has helped take pressure off the province’s 811 health line at a time when callers often have to wait for several hours to speak to a nurse. Many of those who get through don't qualify to be tested but their symptoms still require guidance, investigations or lab work, said Dr. Okhowat.

“We are basically doing triage,” he said. “Especially for unattached patients, there's just nothing available, except for, of course, the emerg., but we don't want them to go there."

Since its launch, more than 6,600 patients have been screened through the online tool. By March 27, the clinic was seeing an average of seven patients an hour in a surge that lasted throughout the weekend and included return patients exhibiting worsening symptoms. At that rate, cleaning staff — what Okhowat calls the “unsung heroes” of the crisis — can spend as much time sterilizing the exam rooms, handles and doorknobs as doctors do with patients.

Despite the spike in patients, Ash said she worries many have begun to stay clear of the FNWD clinic — and the health care system more widely — even as their symptoms get worse. She points to the recent case of a North Van dentist who stayed home to avoid burdening the hospital system; in the end, the man died alone.

“Some people don’t want to bother their physician. They’re there, they’re waiting and they want to help,” she said, adding there's no reason to be ashamed.

In addition to the virtual consultations and visits to the new clinic, FNWD has also stepped up house calls for those who can’t leave home.

Across the road at RCH, the emergency department has been looped in as well, flagging anyone with respiratory or influenza-like symptoms who need to have a follow-up visit at home or get bounced back to emergency. That helps keep pressure off one of the Lower Mainland’s most important trauma hospitals.

For all the provincial health officials’ guarded optimism that B.C.’s social distancing measures are slowing transmission of the virus, Ash warns that the targeted testing they take part in represents a narrow demographic and so could be giving people a false sense of security.

Ash isn’t the only one concerned with the current testing regime. Over the weekend, an emergency room doctor from Royal Columbian and Eagle Ridge hospitals echoed that message in a YouTube video, stating “we are very much under-testing the population.”

If cases really start to spiral, Ash told The Tri-City News the FNW Division has contingency plans to open up a second testing clinic near Eagle Ridge Hospital in Port Moody.

In the meantime, like any form of triage, there’s a real risk patients sent home from the ER could take a turn for the worst, something Okhowat and his colleagues are hoping to catch before it’s too late.

“With COVID-19, I think the scary thing is that there's a lot that we don't know… how it presents, the course of illness and how to predict who will do well and who will not,” he said.

“That's what everybody is bracing for. Everybody's very scared that suddenly, like Italy, like Spain right now, we're going to see the cases rising.”

Read more of our COVID-19 coverage here.