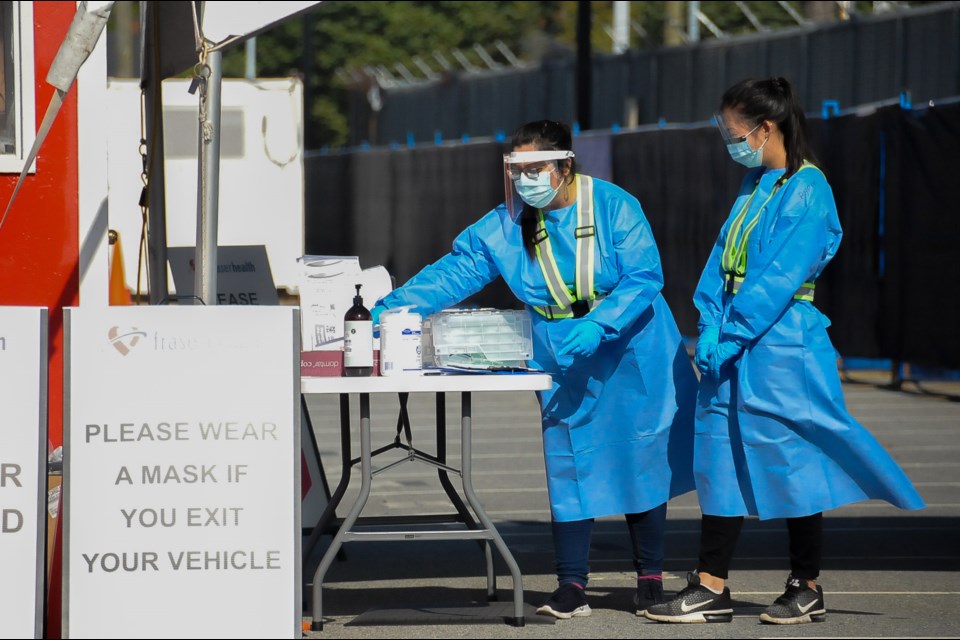

For the second time in as many days, British Columbia has tested over 12,000 people for COVID-19. The all-time single-day testing highs were accomplished the same week Fraser Health ramped up its testing capabilities in the Tri-Cities at the region’s first high-volume testing collection centre in Coquitlam.

On Monday, Fraser Health staff had tested 476 people at the new facility. But the parking lot testing centre has a daily capacity to test up to 800, and with so many months without a centralized high volume clinic, it’s not clear how access to a more centralized testing facility will impact reported cases in the Tri-Cities.

What is becoming clear, according to Provincial Health Officer Dr. Bonnie Henry, is that British Columbia is beginning to win the battle against COVID-19, with new daily cases falling 16% in the previous two weeks.

And it appears the Tri-Cities has done its fair share in contributing to that drop.

Last week, the BC Centre for Disease Control reported a significant drop in the prevalence of COVID-19 cases per 100,000 people in the Tri-Cities’ health delivery area — which also includes Burnaby, New Westminster and Maple Ridge. This week, that trend has held steady with another 88 cases reported in the last seven days.

“Overall cases in B.C. have turned downward, which is awesome,” said Caroline Colijan, a mathematician, epidemiologist and infectious disease modeller at SFU studying the progression of COVID-19.

On Monday, Dr. Henry attributed much of that decline to her Sept. 8 order to shut nightclubs and banquet halls and restrict the consumption of alcohol in bars.

“This virus is in our community. We aren’t going to eradicate it from our community,” she added Thursday. “What these numbers tell us and the active cases tell us, is we’re in that balance.”

But that balance has come at no small cost: on Thursday, British Columbia recorded 110 new cases, pushing the province’s diagnosed COVID-19 cases since the start of the pandemic over the 10,000 mark.

“Today we’ve reached a threshold that makes us pause,” said Dr. Henry. “We know that’s an underrepresentation… [and] as we have seen before, that can change very quickly.”

NOT TIME TO BE COMPLACENT

With cases across the country surging in recent weeks and short term gains rarely a guarantee for the long-term trajectory of the virus, it’s no time to celebrate, say experts.

“We shouldn't get too complacent every time cases turn downward for a week,” said Colijan. “It’s going to be a difficult fall and winter.”

While Henry has said the closure of nightclubs and banquet halls has set us up for a downward trajectory in COVID-19 cases, Colijan cautioned the prevalence of contagion remains high enough that indoor restrictions and closures of high-risk venues need to remain in place.

“Otherwise, that's kind of like saying, ‘Hey, I talked to 50 friends and none of them had a car accident last week. Cars are fine. Throw away your seatbelt,’” she said, adding that at a time when COVID-19 cases are trending up in Ontario and Quebec, British Columbians need to remember they’re not in a bubble.

Robert Huynh/Glacier Media Digital

Yesterday, Canada's Chief public health officer Dr. Theresa Tam said that the number of daily COVID-19 cases reported in Canada increased 40% last week, compared to the week before. She said in a statement that Canada’s average daily count of new COVID-19 cases hit 2,052 over the past seven days, nearly 10 times the low it reached last July.

And the more public life opens in B.C., the more likely a virulent visitor from Ontario or Quebec could set off a large transmission event instead of sporadic clusters, warned Colijan.

“We're all having these same conversations again. It's really frustrating because we’ve had six months,” she said.

“And I think in those six months, maybe we were a bit complacent in thinking, 'OK, so we're north of the border. This makes us really special. We're west of the Rockies. That makes us even more special.’”

WHAT DOES IT MEAN FOR SCHOOLS?

In Quebec, where caseloads are ballooning, the number of exposures reported in schools falls right in line with modelling done by Colijan and her colleagues.

In B.C., however, Colijan worries less consistency in reporting is making it more difficult to reconcile her modelling with reported cases. That’s been especially true in Vancouver Coastal Health, where for a time, health officials were reticent to post school exposure events.

“That trend downward is always a couple of weeks out from transmission today…

So that's probably seeing only the very earliest part of school reopening,” she said, pointing to the latest downturn.

“Quebec schools have been open for longer, so they've had more time to collect exposure data.”

Throughout the course of the pandemic, researchers looking to make sense of the spread of the virus have looked to other jurisdictions. But comparing B.C. to Quebec, for example, leaves out the impact of a more entrenched movement of anti-maskers, conspiracy theorists and numerous hidden challenges with contact tracing, according to Colijan.

“We can look at the States and say, ‘Oh, look at this place.’ But places aren't doing the same thing at the same time. There's no one place exactly like B.C., except it opened schools two weeks earlier,” she said.

Fraser Health School Exposures

What we do know, said Colijan, is that a single case in a school does not mean the virus is necessarily going to spread like wildfire and infect the whole class.

“If that was true, we've had enough exposures that we would've seen it,” she said.

In the last two weeks, three Tri-City schools have been flagged over COVID-19 exposures, including two middle schools in the last two days. Dr. Henry has repeatedly said that such exposures are to be expected, especially when the virus continues to circulate in the community.

“We’re actually testing kids a lot more,” she said Thursday, adding that roughly seven in 1,000 children tested with symptoms are diagnosed as positive.

Dr. Henry has long cited evidence that young children, particularly under the age of ten, are less likely to shed virus and pass it on.

“That still holds,” she added, noting her office conducts “rapid evidence reviews” on a regular basis to assess research coming out from around the world.

But just because there’s some variability does not mean single super-spreading events can’t happen. Indeed, they have in places like Israel and Chile, noted Colijan, also pointing to a West Vancouver elementary school where nine out of 16 student class were recently sent home to self-isolate.

“Those are unlucky events, but there are enough unlucky events in this pandemic that we have a global pandemic,” said Colijan. “We need to think about those unlucky events. They're not just unicorns that we can assume never happened because we're special and we're in B.C.

“We're not magic.”