Long before Steve Chapman joined Coquitlam Search and Rescue and mapped out the wilder places across British Columbia, he was just like any reckless teenager — one with a mountain habit.

Growing up in England, he would tromp around the the mountains of Wales and Scotland, the hills of northern England’s Lake District.

“We’d go to the pub and talk about the near misses,” he told The Tri-City News.

But by the late 1990s, his hobby had quickly evolved from easy trail walks to potentially treacherous ascents, and he soon found himself on the tongue of a glacier in the Swiss Alps. Chapman and two climbing partners crept up the mostly snow-covered route, ticking past 8,000, 9,000, 10,000 feet above sea level. Then, on the only patch of rock on the entire route, something happened.

It could have been someone’s foot. It could have been the rope dragging across a loose patch of rock. All Chapman remembers is waking up on a ledge 10,000 feet up covered in blood.

“I was on the ground and my head was hurting,” he said.

Chapman tried to shout to his partners but couldn’t find the words — the rock that had struck his head had caved in his skull and damaged the part of the brain that controls speech.

“I couldn't put any language together whatsoever,” he said. “It was just coming out as complete gibberish.”

With his friends' help, he managed to make it to an alpine hut a little way up the mountain. From there, they were able to radio a search and rescue helicopter, which long-lined him down to a hospital.

It took Chapman six days practising a single phrase before he could call his parents: “I’d just had a little bump on the head,” he told them. “Don’t worry, I’ll be home soon.”

It took him another four months to recover 90% of his speech.

The swift rescue — and temporarily losing the ability to communicate — would prove a watershed moment for Chapman, one that would eventually lead him away from corporate life and into a lifelong pursuit to help others find the same narrow window of escape he had.

A search and rescue blind spot

In the two decades since Chapman’s accident in the Swiss Alps, technology has continued its steady march forward. But where a radio in a mountain hut saved him in Europe, the rugged and broken terrain of Canada’s Coast Range offered Chapman a glimpse into the limits of an analog world.

“Communication is always our Achilles heel on a search. You get dead spots on the radio, bad reception,” said Chapman. “I realized the infrastructure isn’t here.”

"Here" is the the wilderness around the Tri-Cities and Metro Vancouver, which he has explored both recreationally since he arrived in Canada in 2001 and as a volunteer with Coquitlam Search and Rescue (SAR) for the last six years.

During his time here, his passion for the outdoors and making it safe for others led him to abandon a career engineering backend solutions in digital telephone systems.

In Coquitlam, he met a talented software engineer named Steve Graham and, from the beginning, the pair dove into mapmaking and the challenge of devising tomorrow’s solution to personal navigation.

They would launched a line of custom travel DVD-ROMs meant to replace cumbersome paper maps. But when a failed pitch on CBC's Dragons' Den put the brakes on those plans, Chapman kept creating, mapping out vast swaths of the province and putting navigation into the hands of regular people.

At the same time, working with Coquitlam SAR, he saw first-hand how easy it was for communication to break down when someone is in trouble in the backcountry, and where rescues can rely on patchy cellphone signals and the foresight of an aspiring adventurer to leave their plans behind.

The scale was daunting. Of the approximately 2,000 rescues performed across Canada every year, nearly 1,700 occur in British Columbia.

Graham and Chapman spent thousands of hours sketching out, developing and testing systems and technology to find a way to call for help.

Now, after over a year of work, they have an answer.

Overdue

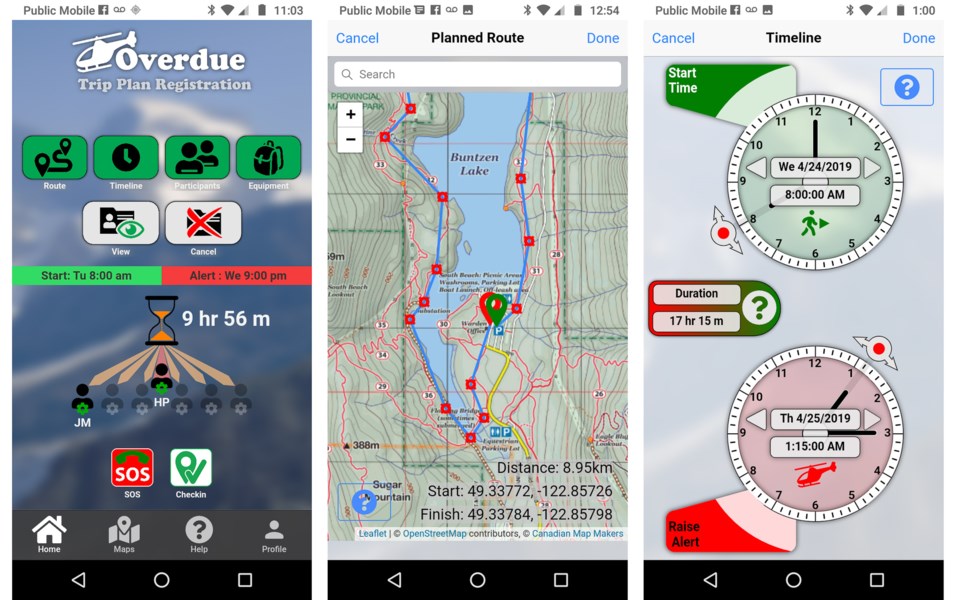

In July, Chapman and Graham will launch Overdue, a smart phone application combining the entire knowledge DNA of what it takes to stay safe in the mountains. By closing the loop between people out in nature and SAR teams, Chapman says Overdue will offer an automated trail of digital breadcrumbs for anyone who hasn’t checked in.

It starts with a trip plan. By combining a baseline set of open-source maps with Chapman’s detailed topographic versions, the app has you input how long you’ll be out and which route you’ll take.

From there, you’re prompted by a set of questions, such as whether you will cross steep snow or ice, enter terrain with large, dangerous animals, or pass into an avalanche zone.

Based on your answers, the app will suggest a list of gear to take with you, from crampons to bear mace.

Next, you add a selfie and up to six contacts — people who will be notified if you haven’t checked in before your expected return.

Fifteen minutes before you’re overdue, the program will sound an alarm, send you a text message and call you with an automated voice in either English, French or German (Mandarin will be added next, Chapman says).

If you don’t check in, the app works its way down your contact list until someone answers, sending a text with your trip plan and an automated voice call asking them to confirm that they’ll notify emergency services.

“Is it 100% foolproof? Of course not. An SMS can go into the ether and disappear,” said Chapman. “But it's adding a lot more safety to what many people have now.”

An analog advantage

While the Overdue app is his latest venture, Chapman has long chased the latest technology.

But in an era when we can instantly beam messages to a loved one or have a GPS app guide us through the cobbled alleys of Barcelona, he’ll be the first to acknowledge its limits.

“People become so reliant on their phones, you know?” he said. “They think they've got everything until that information turns out to be wrong or their phone dies.”

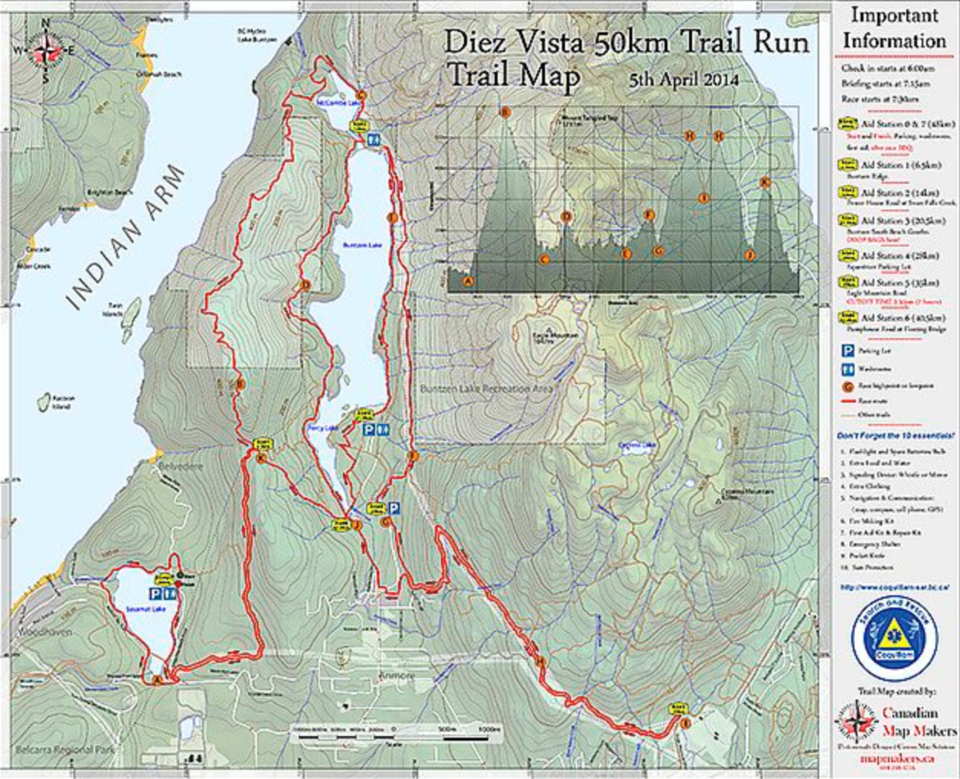

As a cartographer, he has made it his mission to bring back the paper map, and has produced a vast portfolio of work, from sprawling maps of the Roman Empire to maps of more than 500 km of biking and hiking trails across the Tri-Cities.

Locally, Chapman is building a small but loyal group that still looks to paper and compass: More than 2,500 people have picked up copies of his topographical map of the area surrounding Buntzen and Pitt Lakes.

With Overdue, he’s now hoping to tap into the more casual hiker, the Instagram generation, which has known nothing but digital technology. To that end, Overdue will offer paper maps, too.

“The technology should be viewed as the backup to the old-fashioned stuff, not the other way around."

SIDEBAR: THE DANGERS OF AUTOMATED NAVIGATION

The increased use of digital navigation tools may be affecting our brains in dangerous and unforeseen ways.

In her recent book Wayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the World, journalist and author Maura O’Connor draws on a growing body of scientific research that suggests choosing to turn left or right could be as important for your brain as regular exercise is for your body.

O’Connor points to a study where 24 participants are tasked with navigating the Soho neighbourhood of London, U.K. When they had to use their spatial reasoning skills and make active choices in navigating the streets, their hippocampus — a part of the brain where we keep our spatial knowledge, build our cognitive maps and store episodic memory — lit up.

In what O’Connor describes as “the locus of our autobiography,” the hippocampus allows us to imagine the future and, in so doing, work out what’s behind a corner.

But when the participants of the study were told which direction to turn, that part of the brain showed no activity. Navigating on our own, O’Connor suggests in Wayfinding, could offer us the very stimulus in short supply among victims of Alzheimer's and PTSD, all of whom exhibit an atrophied hippocampus.

Letting an algorithm guide us, it turns out, could be more dangerous than once thought.

Stefan Labbé