Don Simpson may be partially blind, he may use his walker a little more than he used to, but as one of Port Coquitlam’s oldest turned 106 this week at Mayfair Terrace, he still has it in him to woo a crowd of 30 peers with the story of a life well-lived.

An only child, his life began in Edmonton in 1913, a year after the Titanic sunk and the same year Al Capone was booted out of high school.

Simpson described his early years as full of adventure, moving from one Alberta town to another as his father went looking for work as a locomotive engineer.

When the First World War broke out, Simpson's father shipped out to Europe, leaving him and his mother behind to live a frontier existence in the town of Edson.

When the war ended in 1919, Simpson's father returned from the front reeling with the effects of a mustard gas attack. Unable to keep down anything but cooked bread and milk, his father moved the family to Vancouver, where he could recover at the Shaughnessy Veterans Hospital and where Simpson's mother could finally “get away from the wolves.”

By the late 1920s, Simpson had grown into a teenager, curiously meeting the same girl at the same spot every morning on his walk to school.

“I think there was a little winking of the eye,” Simpson said. “I had my eye on her and she had her eye on me.”

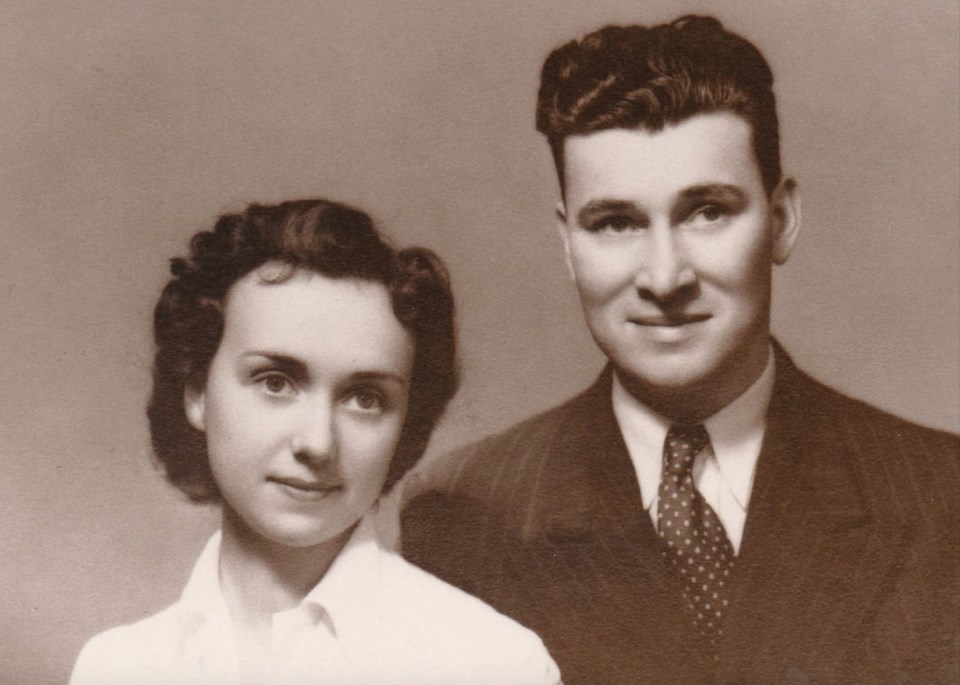

Don and the later-to-be Jean Simpson fell for each other. But as the 1930s got under way, the Depression forced the couple to abandon the prospect of an easy life.

After a stint at a salmon can factory, Simpson set off across the country with a repair gang for the Canadian National Telegraph Company.

“I rebuilt poll lines, from the rice mills on Lulu Island out to Manitoba,” he said.

For three years, Simpson lived in and out of boxcars — six men to a car, all stacked in bunks with a potbelly stove in the middle to keep them warm. At 50 cents an hour, the wages were good for a Depression-era gig.

Eight years after those first winks on the way to school, Don and Jean got married. By then it was 1940 and while the economy was up, the world was once again plunged into war.

Simpson signed up for the navy, but in what he sees as an odd conspiracy, “All the boys from Saskatchewan got into the navy and the Pacific coast guys got into the army.”

Because of his experience building communication lines, the army pulled him off combat duty and put him in charge of building and maintaining phone lines.

Throughout the course of the war, he would oversee the six-month construction of a telephone line from Williams Lake to Bella Coola “to warn everyone of a Japanese attack.” Around the Lower Mainland, he maintained communications for the three anti-aircraft batteries at Point Grey, Stanley Park and Point Atkinson.

Of course, the Japanese never came — save for a supposed submarine attack on Vancouver Island — and when the war ended in 1945, Simpson kept doing what he did best, electrifying and stringing up telephone lines for the likes of the British Columbia Electric Company (the precursor of BC Hydro) and the B.C. Telephone Company.

From groundman to lineman to cable splitter, Simpson pulled some of the first cables across the Georgia Strait to Bowen and Vancouver Island.

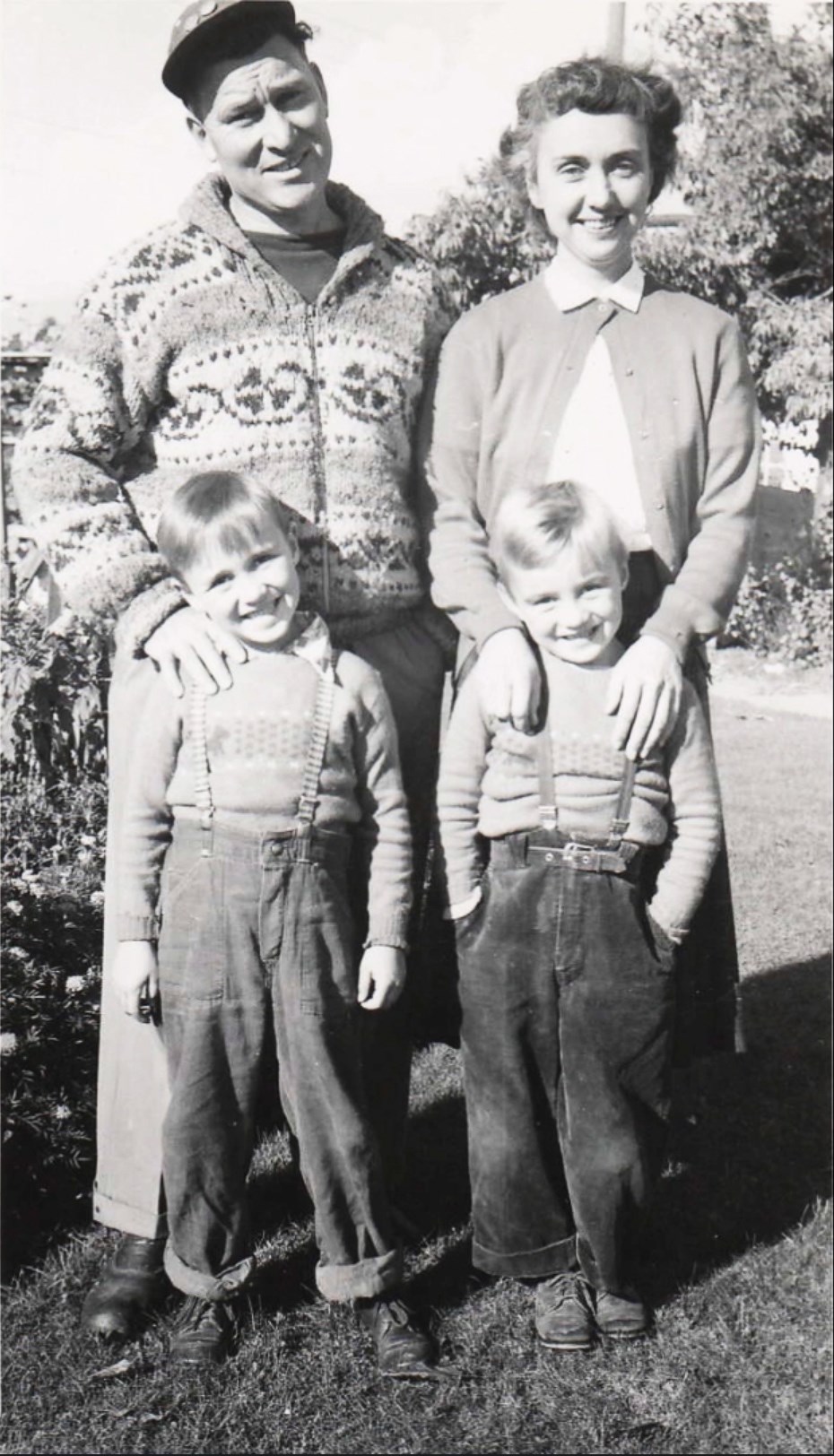

By 1949, Don and Jean had their first son, Lloyd, and two years later a second, Blaire.

Never having made it into the navy during the war, Simpson took things into his own hands, picking up a handful of boats and eventually building Ambler, a 40-footer he used to cruise the coast with his family.

In 1972, two years before he retired, he became Commodore of the Burrard Yacht Club, and at 63, decided to take his boating life to the next level.

“What started me was National Geographic,” he said.

Over the next 18 years, Don and Jean travelled the world on passenger freight ships, passing through the Panama Canal a dozen times and circumnavigating South America and Africa, seeing “all the animals you could see… thousands of them.”

“One time, we spent 149 days on one,” he said.

But that life came to a halt when he turned 81 and the ship’s rules and regulations required a doctor to be on board.

In 2004, his wife Jean passed away at 92, and for the next several years he lived alone in an apartment in West Vancouver.

“You spend a few years alone, you get tired of looking after yourself,” he told The Tri-City News.

So at 100-years-old, Simpson moved to Port Coquitlam, settling down at Mayfair Terrace. Where once he would cross continents and oceans, he now makes the odd trip to Radium Hot Springs, Whistler or down to White Rock.

These days, Simpson is a magnate of the home's social scene. At 106, he's the founding member and ‘King’ of the Century Club. “That’s why I wear this,” he said, pointing to a crown on his head.

Despite his age, Simpson has a sharp mind, biting sense of humour and a flair for the dramatic. On Valentine’s Day, he runs a seniors-for-seniors hugging booth (five dollars for a 'special hug'), and he’s a regular at ‘The 151 Club,’ where he and about five other seniors shoot back overproof rum once a month.

“You know when the 151 Club has met,” said one employee at the home. “He’ll be weaving down the hallway.”

When asked his secret to such a long life, Simpson paused long enough for a few in the audience to venture a guess.

“Alcohol!” shouted one of the dozens of seniors in the crowd. “Apple juice?” laughed another as the crowd leaned in to hear over the muffled microphone.

“I have no idea,” said Simpson with a chuckle.