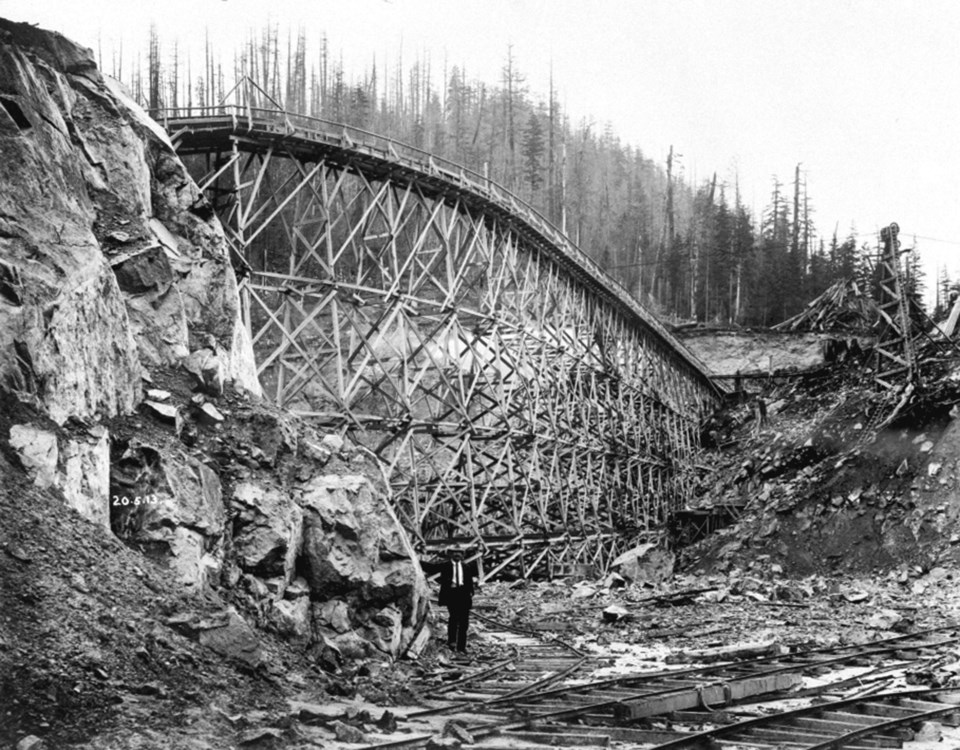

Over 100 years ago, the coho salmon of the Coquitlam River were wiped out in a massive project that would bring electricity to the streets of Vancouver.

Now, the extirpated species may get another chance, according to a plan to annually transport up to 100 returning coho salmon adults and 40,000 juveniles upstream of the Coquitlam Dam.

“A couple hundred fish is a drop in the bucket in terms of productivity, but still significant considering we haven’t had any there for over a hundred years,” said Craig Orr, a professor at SFU’s ecological restoration program and an environmental consultant for the Kwikwetlem First Nation (KFN).

The plan comes as Metro Vancouver moves to position the Coquitlam Dam as the backbone of the region’s water infrastructure, something Orr said could one day lead to a collision between the interests of a growing human population and struggling fish.

Salmon are already under threat.

According to a devastating Department of Fisheries and Oceans report last summer, coho, chinook and sockeye numbers are declining throughout the province, all under pressure from warmer ocean temperatures, which limit the abundance of more nutritious forms of zooplankton, a key food source for salmon.

Last year was one of the worst for sockeye salmon in the Fraser River, with returns found to be the lowest since record-keeping began in 1893.

Beautiful female sockeye, just the second "red fish up the river" in 2020 in the Coquitlam River (and in the past 2 years). Silvery early return, remnant, reminder, and hope for this unique early Fraser race of sockeye. #redfishuptheriver #endangeredsockeye #defendwildfish pic.twitter.com/4slziDKuTc

— Craig Orr (@CraigOrr_) July 27, 2020

The steep decline has had a profound impact on the fishing industry, the ecosystem the fish support and First Nations like KFN. Like all Pacific salmon once plentiful in the Coquitlam River, coho formed an important part of community’s food source and identity, so much so that the name Kwikwetlem is translated from the traditional Halkomelem language as “red fish up the river.”

KFN has spent years in collaboration with community groups and conservationists like Craig Orr trying to re-introduce sockeye salmon into the Coquitlam River. But despite all that effort, so far this year, only two have returned.

“Just getting some coho back made [KFN] feel we were restoring something that was lost,” said Orr. “In a bad news situation, we’re seeing some rays of hope.”

THE PLAN

The plan to reintroduce the species was presented in a Metro Vancouver staff report last week, which backed the joint request by Fisheries and Oceans Canada and KFN.

The first round of transports is proposed for sometime after October 2020, when adult coho salmon are expected to return to the lower Coquitlam River.

In a 2019 letter to Metro Vancouver officially proposing the plan, DFO senior biologist Dave Nanson writes that the upper Coquitlam River contains some of the “most pristine salmonid habitat in this region,” making it an ideal candidate to help replenish stocks “resilient to future stressors such as climate change.” That’s because the reintroduction could improve the genetic diversity of the wild fish population, notes the report.

The DFO request suggests the Port Coquitlam and District Hunting & Fishing Club capture and transport the fish to “on-drainage release locations along the lakeshore and adjacent creeks.” The Kwikwetlem Sockeye Restoration Program, meanwhile, would be tasked with monitoring the success of the transport and find ways to improve the paths open to the fish as they migrate downstream.

The transport of 100 adults is based on the estimated carrying capacity of the watershed above the dam.

According to the report, Metro staff don’t anticipate any “impacts to water quality or water utility operations” and there are “no financial implications from this request.”

Of the nine potential risks to water quality, only the introduction of coliform flora was assessed to have a “moderate probability of occurrence with moderate confidence,” though that could be reduced to a “low probability” following water treatment.

In fact, earlier studies cited by the DFO biologist found up to 15,000 adult sockeye could be reintroduced to the Coquitlam reservoir and still cause “negligible change in the water quality.”

And with the future of Metro Vancouver’s water supply leaning heavily on the Coquitlam reservoir, that matters.

COQUITLAM DAM THE FUTURE OF VANCOUVER’S WATER

Where over 100 years ago the Coquitlam reservoir spurred the electrification of the Metro region, today planners are preparing to shift its role and position it as the backbone of the entire region’s source of freshwater.

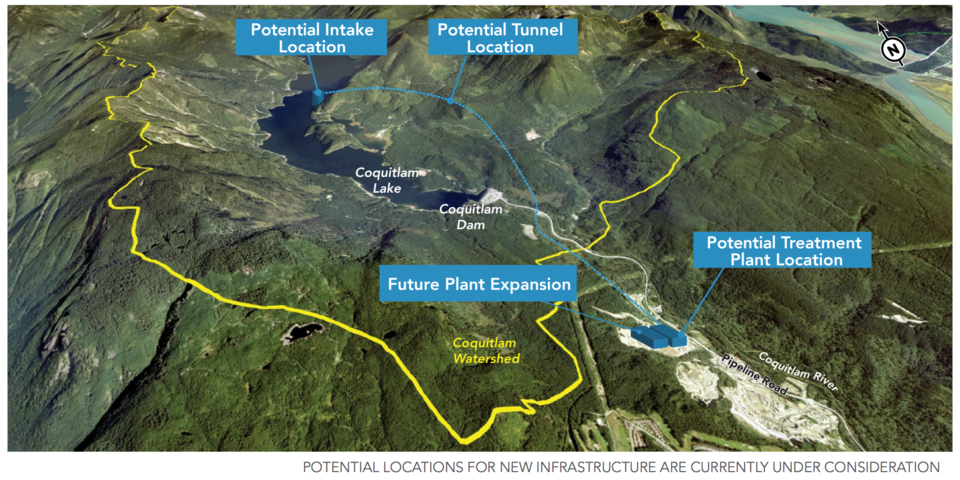

Climate change is expected to drive the shrinking of spring snowpacks by up to 60% and lead to decreases in summer rain by up to 20% by 2050. That means less water to replenish reservoirs when the region needs it most. Add that to a growing population and under the status quo, Metro Vancouver will run into shortfalls over the next 30 years, according to a recent report looking at the future of the region’s water supply.

“[By] say, the year 2050, we’re looking at another million people living in the region. That’s the key driver,” said Inder Singh, the regional body’s director of interagency projects and quality control in water services.

Singh said that as we pass 2100, the region will need up to 600 billion litres of water every year, a steep uptick from the 390 billion litres pumped from the Seymour, Capilano and Coquitlam reservoirs.

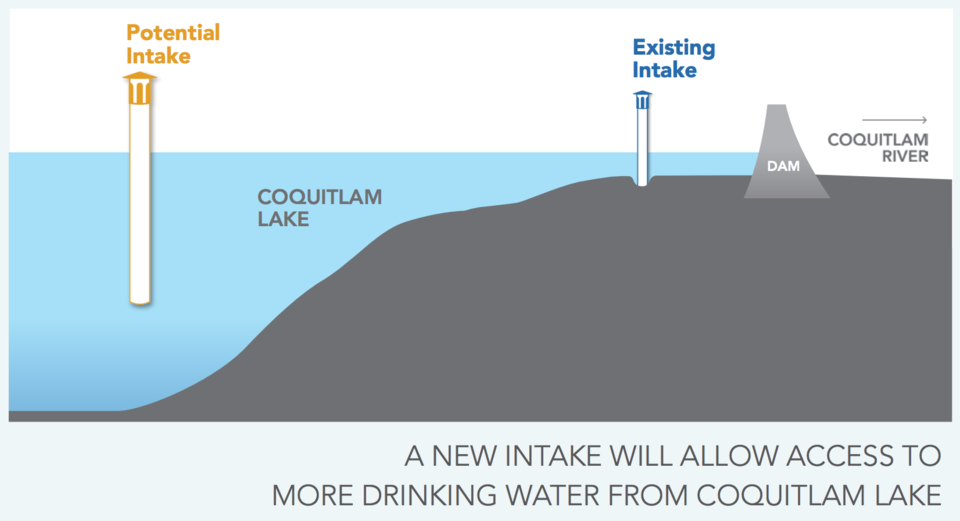

With the storage capacity of those reservoirs not getting any bigger, Metro is looking to go deeper, so it can draw water into the hottest and driest summer months. Only the Coquitlam Dam has the potential for that kind of retrofit. And so Metro planners are hard at work drawing up plans for critical infrastructure that will deepen the intake at the reservoir. Much of that water will feed the fast-growing municipalities like Surrey and Langley.

“We’ll be getting another 100 billion litres of static storage,” said Singh, enough to see the region until roughly 2070 at which point Metro will need to look further afield.

What happens next will depend on where the population goes, both fish and human.

HUMAN VS. FISH

BC Hydro recently approved funding for a small, standalone hatchery at the base of the Coquitlam Dam to be operated by KFN in an effort to temporarily boost sockeye numbers.

But long-term solutions come back to the problem of the dam, and Orr said KFN has been working with some of the leading experts in the world on how to clear a path for the fish out of the upper watershed, past the dam and towards the Pacific Ocean.

One solution could be to carve a notch out of the dam as an escape route; another piece of technology, known as “the gulper,” utilizes a sweeping boom to guide the fish into a pump — most solutions are expensive, complex fixes.

“You need to make sure you’re plans don’t impinge on the fish,” said Orr. “We don’t want to see all this work that’s put in to restore salmon populations to go for nought.”

And as more pressure is put on Coquitlam Dam to supply the region with water, Orr worries what it will mean for downstream flows.

Other salmon species, like chum and steelhead, have seen some limited success in the eddies and pools of the upper watershed. And Orr suspects that’s a result of higher discharges released from the dam since 2005, but the data is still coming in and he said they’re still “crunching the numbers.”

“It’s a heavily urbanized area. There’s only a limited amount of water,” he said. “I don’t think down the road we’re going to see enough water for people and fish.”