Upriver from where the Nahatlatch tributary falls out of the mountains and into the Fraser Canyon, empty lots sit waiting for a buyer to park an RV or put up a rustic cabin.

“If you’re lucky, you have power,” said Agassiz-based realtor Freddy Marks, who specializes in selling recreational properties from Hope up into the Cariboo.

Marks says he normally fields two to three calls a day from potential buyers looking for a haven to escape the city. But when a Port Coquitlam resident called him up two weeks ago looking for a chunk of land along the banks of the mountain river, business had already tripled.

Competition for such properties, which range from around $100,000 up to $500,000, has become fierce, with “normal, working-class people” driving out from places like Vancouver, Surrey and the Tri-Cities to put down an offer. What might have appealed to the odd family three months ago, doesn’t sound so crazy for people anymore, said Marks.

“If you’re living in a two-room condo, and you’re pretty much in jail for two weeks, you think ‘let’s get the hell out of here,’” he said.

For decades, Metro Vancouverites have increasingly moved skyward, with dense urban projects promising a new kind of lifestyle. Living a small life in a small apartment meant access to a big public life.

“This was the ‘grand bargain,’” said Andy Yan, urban planner and head of the City Program at Simon Fraser University. “But what happens in a pandemic when that condominium is not only a place where you live, but it's your workplace, it's a daycare, it's a restaurant?”

As British Columbia emerges out of the crisis phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, how the legacy of the virus will affect city life remains an open question planners, businesses and your average worker are only starting to grapple with.

The evolution of cities has long intertwined with the outbreak of disease. Take the extensive Roman waterworks or the work of English physician John Snow — considered the grandfather of modern epidemiology — who halted a severe cholera outbreak in 1854 London by knocking the handle off a poisoned well.

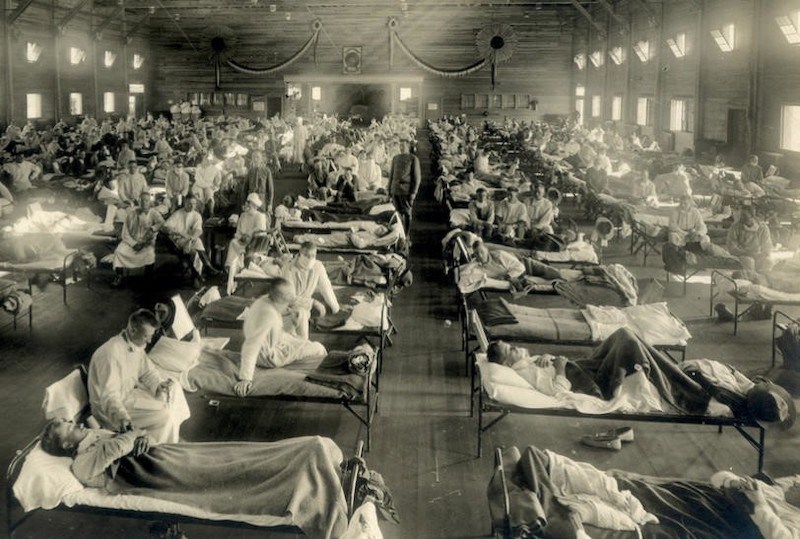

Still, infectious diseases like influenza, pneumonia and tuberculosis remained the leading cause of death throughout the early half of the 20th century.

That’s when the leading causes of morbidity began to evolve. As more cars hit the road, deadly accidents spiked, a cause of death finally overtaken by non-communicable diseases as sedentary lifestyles and bad habits caught up with the population.

“Now it's lifestyle diseases — obesity, diabetes, heart disease — that kill us,” said Yan.

It's this kind of long-count thinking that has prompted Metro Vancouver, TransLink and many of the region's municipalities to push for dense, urban neighbourhoods connected by a robust system of public transportation and greenways.

So it was no surprise when, last year, the two regional bodies came together to map out how Metro Vancouver could change over the next 30 years. The report, released last April, describes four possible futures, from steady growth to a decline in global trade, triggering a move to local production and self-sufficiency.

But while the report was careful to consider the two flip sides of automation and the shocks of climate change, the spread of a global pandemic at the scale of COVID-19 is absent from their projections. Now, many of the assumptions that underpinned the region's growth — such as constant growth in transit ridership — have been thrown into question as people look to avoid touch points and crowded public spaces.

“Will people feel comfortable going back to transit or will they stay in their cars?” questioned Yan. “We don’t know… but we might have to think about crushing the commute.”

That could bode well for cities like Coquitlam, which last year unveiled its own 25-year plan that would transform its City Centre from a suburban shopping hub to an urban downtown.

“If you look around Coquitlam Centre, it's amazing to see how fast that growth has already occurred,” said Yan. “What happens when you don't view them as suburbs of Vancouver, but rather their own kind of centres?"

Michael Hind, who leads the Tri-City Chamber of Commerce, said he expects one of the legacies of the COVID-19 crisis will, indeed, mean more people looking to work in the same community they live in.

“It augurs well for communities like the Tri-Cities,” Hind said.

Just how businesses and the people around them will bounce back is less clear. Unlike the 2008 financial crisis, where the whole economy slowed down, the current pandemic has had an outsized impact on certain sectors of the economy, like retail and restaurants.

Already stumbling against online sellers like Amazon, COVID-19 appears to have accelerated retail's decline, permanently shuttering iconic stores like Army & Navy. That along with the decimation of bars, restaurants and cafes, could present a huge challenge to people like Andrew Merrill, Coquitlam’s manager of community planning.

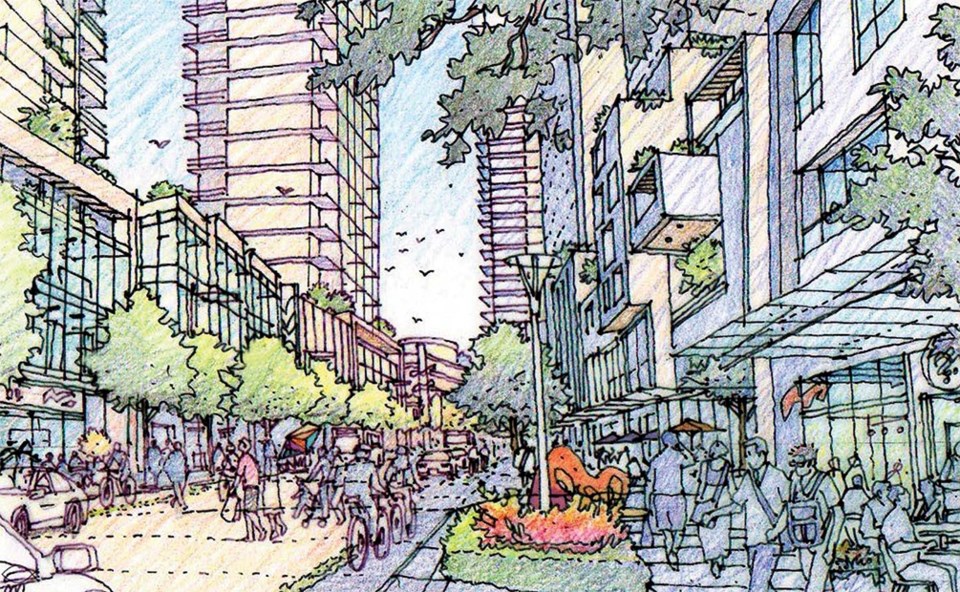

When, last year, Merrill and his team presented council with the city’s 25-year plan, it showed large swaths of concrete parking lots replaced by a variety of public amenities, all interlaced with mixed high-rise living. Key to that plan is the bustling street life made possible by ground-floor restaurants and retail spaces.

“Maybe we decide we don't want to go back to restaurants and we just want a vending machine coffee from now on because it's safe and sanitary,” said Merrill.

“If those [ground-floor businesses] are going away… we don't have a lot of good alternatives.”

It’s not just an urban form problem. If the thousands of retail and restaurant jobs stay gone — and they make up the largest share of the region’s 1.2 million-person workforce — the ripple effects could be disastrous.

“Our society as a whole was already seeing increasing income inequality causing social challenges over the last decade or even longer. You know, this is the kind of crisis that can actually amplify that,” said Merrill.

In many ways, it already has. Yan points to the workers at the Superior Poultry plant in Coquitlam, where the city’s largest outbreak hit new Canadians earning relatively low-incomes the hardest.

“Who is working in these plants? Newer immigrants, blue-collar folks who are struggling in this economy,” said Yan. “They’re not living in necessarily dense neighbourhoods... they’re overcrowded, several generations living in a single basement suite.”

And many couldn’t dream of buying even the cheapest riverfront property realtors like Freddy Marks are offering as safe havens across rural B.C.

On the cusp of a staged re-opening, most British Columbians are still in a crisis mode, trying to keep paycheques coming in and businesses going one day at a time.

As provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry recently put it, we are just reaching "the end of our beginning" phase of this pandemic. How city life will change for what some are now calling "Generation C" remains an open question.

“Will we start reopening things this weekend and that’s it? Or is this just the first of a series of waves of pandemics?” said Merrill.

“We need more data.”