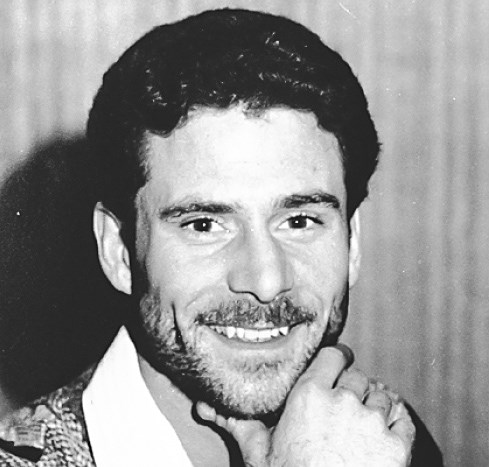

At around 1:30 a.m. on Aug. 13, 1994, Graham Niven ambled towards a Mac’s convenience store in strip mall on Ridgeway Avenue in Coquitlam.

The 31-year-old had recently returned to the Lower Mainland from Calgary and, after a playing few games of pool at the John B Neighbourhood Pub on Austin Avenue, he left, meeting 14-year-old Kevin Valin, a Quebec resident who was stuck for a ride to his father’s house in Burnaby, where he was spending the summer.

Niven offered the teenager some money to get home but because the buses had stopped running, the two of them went to the Mac’s to call a taxi.

Only neighbours and certain parents knew it, but the increasingly scruffy strip of small businesses on Ridgeway had become a way station for young people out drinking, looking to score drugs and, for some, getting pulled into prostitution.

As Niven and Valin walked out of the convenience store to wait for the taxi, they crossed paths with four teenagers on their way in to buy food. Niven and the other teens started chatting, and the topic of drugs came up.

Three years later, Valin would tell a court that when 18-year-old Stephen Stark said he did heroin, Niven warned him it would mess up his head.

That’s when Stark, who Valin would describe as “the fighter,” got angry.

“I’ll f--king cut a hole in your head,” Valin remembers Stark saying.

Just then, someone else arrived at the store. When Niven opened the door for the man, Stark warned Niven, “Go in. That’s your chance. Save yourself.”

Stark then grabbed Niven, smashed him into the store’s plate glass window and threw him on to the pavement, where he cracked his skull on the concrete.

Stark jumped on top of Niven and started punching him in the gut. Then, one of the other three teenagers Stark arrived with, 15-year-old John Biniaris — Valin described him as “the stomper” — entered the fray, repeatedly kicking Niven’s head into the ground before the two aggressors fled the scene.

When police and ambulance arrived, the 30-second attack had left Niven unconscious with an imprint of Biniaris’s running shoe still visible on his forehead. Paramedics rushed him to Royal Columbian Hospital but Niven never regained consciousness.

Roughly 10 hours later, he was pronounced dead.

SHOCK, OUTRAGE, ACTION

Coquitlam RCMP arrested Stark and Biniaris at 11 p.m. the same day and, as news of the murder spread, the outpouring of grief quickly turned to outrage.

The single act of violence was a culmination of a rising tide of crime and would transform the Tri-Cities in ways nobody could have predicted.

“How could two young men commit such a brutal murder?” many openly questioned.

Over the coming weeks, letters poured into The Tri-City News from community members trying to make sense of the murder.

“The death of Graham Niven must have some meaning,” opened an editorial in this paper the week he died.

At the time, crime was peaking across Canada and drew plenty of political heat. A number of U.S. states had just begun rolling out three-strikes laws as part of a popular campaign to “get tough” on crime.

For many people in the Tri-Cities, Niven’s murder represented the latest brutal example of a flawed justice system, a horrific spark that ignited thousands of citizens to call on government to revamp what was then known as the Young Offenders Act (YOA).

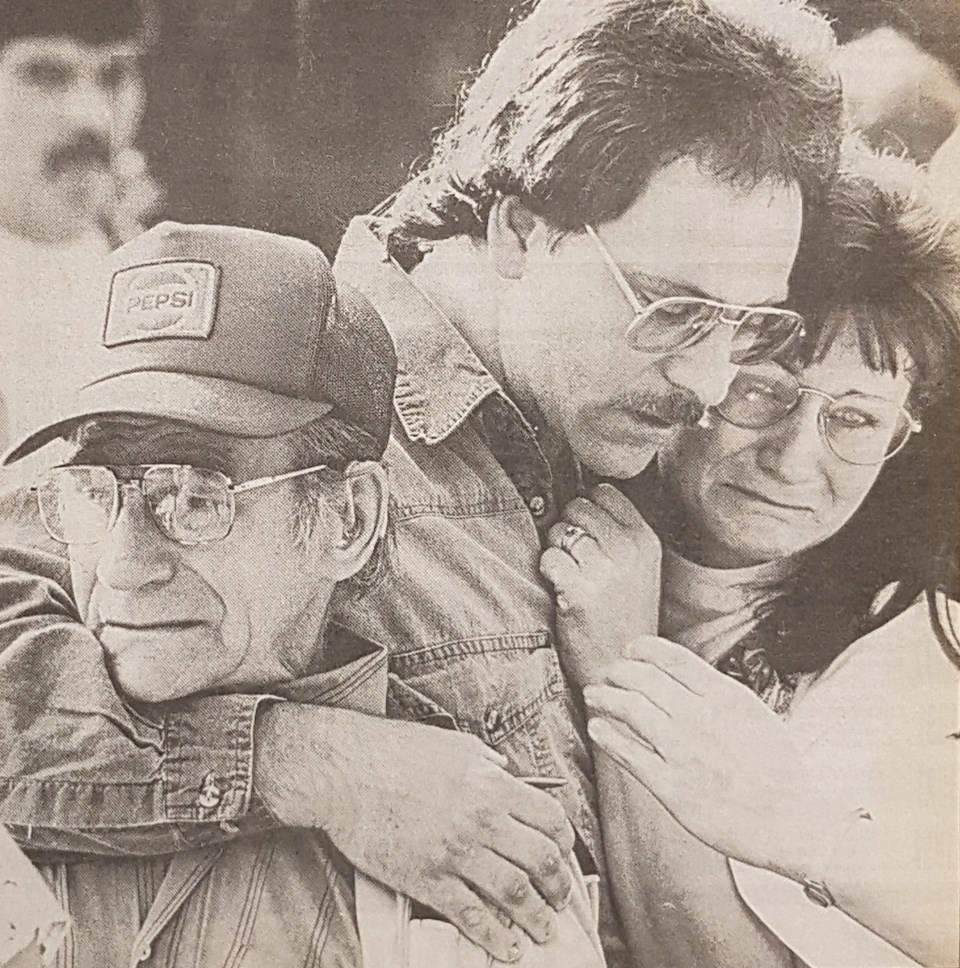

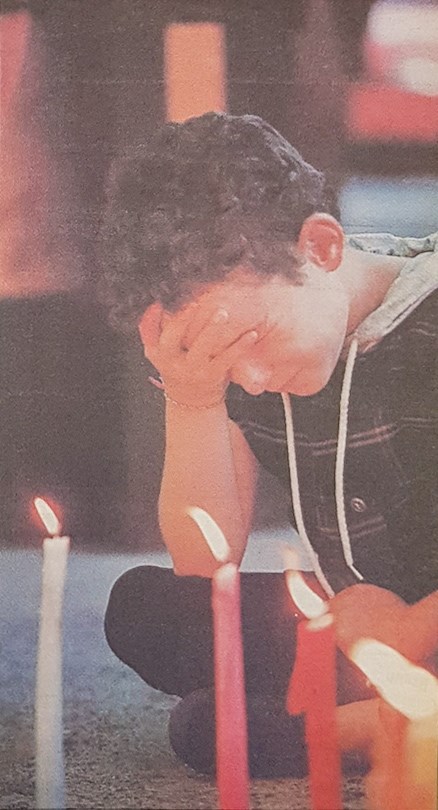

Within days, Coquitlam's mayor, Lou Sekora, started circulating a petition to reform the YOA and, on Aug. 22, 300 people stood shoulder to shoulder with then Coquitlam-Port Moody Reform MP Sharon Hayes at the Port Moody recreation centre. In a candlelight vigil, community members and family embraced in an outpouring of public grief.

By the end of the month, an ad-hoc victims' rights group came together under the name Tri-City Citizens for Justice and Youth. Hayes joined the group’s steering committee, along with Niven’s father, Robert Niven, and Chuck Cadman, another dad whose son, Jesse, had been senselessly stabbed to death by minors two years earlier.

“It was a very scary time. It really made people feel unsafe in their own community,” said Diane Sowden, who also joined the group. “There was a lot of things happening in the communities with drugs, violence and the sex trade that the average person was not aware of.”

Like Cadman, Sowden had been waging her own private campaign to change the YOA. But where Cadman was lobbying to ramp up penalties for young criminals, Sowden struggled to have a stronger hand in the life of her daughter, who was then pivoting between the streets and Willingdon Youth Detention Centre after she got hooked on crack and was sold to a pimp to repay a drug debt.

As Sowden’s daughter was slipping through her fingers, lost to a world of drugs and prostitution, the young mother struggled to get her daughter off the streets and remain in rehab.

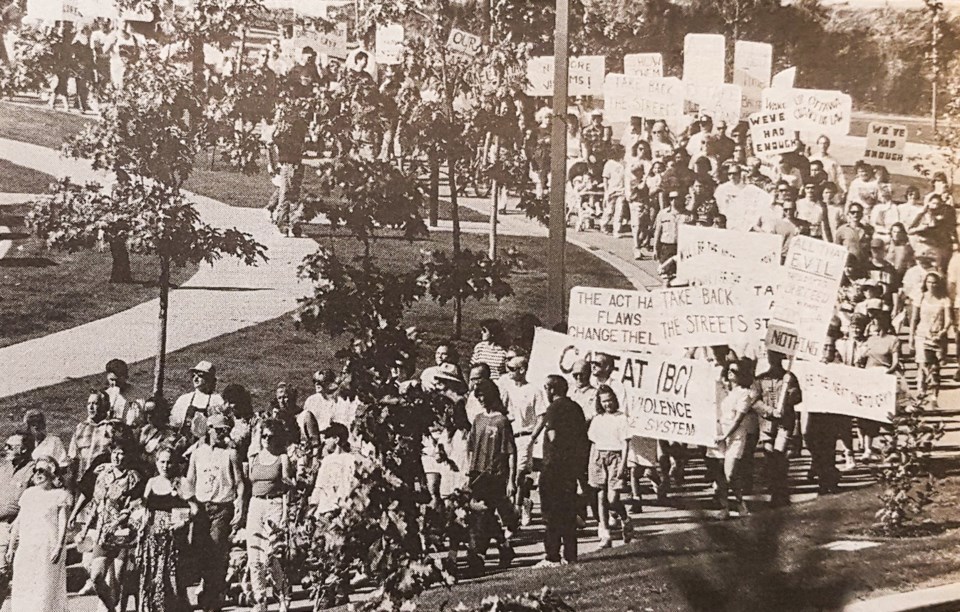

The summer turned to fall and the number of Tri-City petitioners ticked into the thousands. On Saturday, Sept. 28, more than 5,000 people marched to Coquitlam's Town Centre Stadium in what Sowden said was the largest protest rally she’s ever seen in the Tri-Cities.

“WE’VE HAD ENOUGH,” read one protest sign. “TAKE BACK THE STREETS,” read another.

In the end, nearly 20,000 people signed the petition to overhaul the Young Offenders Act.

“It was the first time I spoke publicly about my daughter's situation,” Sowden recently told The Tri-City News. “It was huge.”

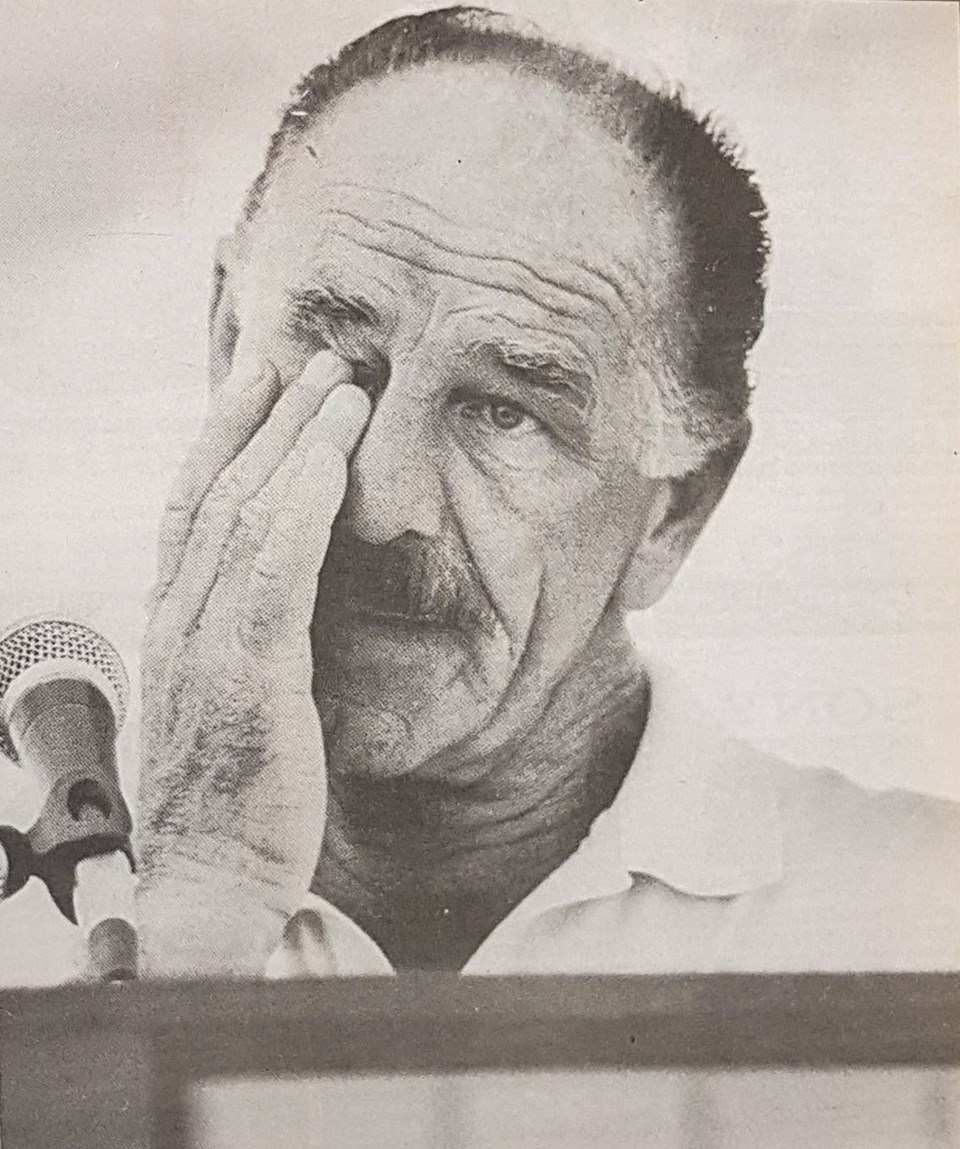

Robert Niven appeared, too, breaking down during his speech. “We want to make our streets safe for every one of us — you and me included — to walk in."

Cadman, who would later go on to champion youth justice as an MP, said, “Frankly, I’m getting a little tired of meeting grieving parents like Bob.”

Stark was convicted of second-degree murder in 1995 and, after having his case raised to adult court, Biniaris was convicted of the same crime in 1996.

In the meantime, reform at the national level was slowly marching forward — maximum youth sentences for serious crimes crept up to 10 years by the late 1990s, a knee-jerk reaction to public pressure, Sowden calls it.

“If your child has been murdered, it is very easy to have the communities rally around you. I mean, they should," she said. "But if you're on the other side, it's very scary. It’s a silent group of parents."

COMMUNITY ACTION

From parents to police and politicians, the murder of Graham Niven sparked a realization that more needed to be done for young people in the Tri-Cities, a tragic moment that formed the genesis of many of the youth social services that serve the community today.

The year Niven was killed, Sowden founded the Children of the Street Society and, until her retirement in June, the former Coquitlam school trustee continued to work as a relentless advocate for trafficked children.

Others, like Sandy Burpee, were disgusted by the widespread calls to give longer, adult sentences to teenagers and children.

“I thought at the time that there were at least two tragedies here: One, obviously, was Graham Niven being in the wrong place at the wrong time; and the other was the youth [Biniaris].

“At that rally, the theme was a very punitive response to justice. And I just felt that did not respond to underlying issues that led to this kind of incident in the first place. And that maybe it made people feel good but it would achieve nothing.”

That November, Burpee launched Together Against Violence, a month-long marathon of activities designed to bring awareness to the community. And while it lasted another five years, the big change came at the turn of the millennium, when Burpee secured funding from the three cities, plus Anmore and Belcarra, to launch one of the first restorative justice programs in the province, eventually known as Communities Embracing Restorative Action (CERA).

From the streets of Ireland following "The Troubles" to the ever-evolving peace process in Colombia, restorative justice has played out in different ways around the world. What each case has in common is to provide an alternative to the court system. Victims, perpetrator and families often sit down with a facilitator over weeks, months and even years to try and right the wrong.

“It gives the victim a chance to be heard and gives the perpetrator a chance to explain why they got involved in it in the first place,” said Stacey Robinsmith, a high school teacher and current chair of CERA’s board of directors.

Like other restorative justice organizations across Canada, CERA has carved out a space for itself following the enactment of the Youth Criminal Justice Act in 2002. While lumping violent, high-risk offenders into one category with the option of longer sentences, the law also opened up the door for police to use their discretion in less serious cases.

CERA got its first referral in January 2000 and, as the decade wore on, more came filtering in from police agencies, school districts, ICBC and Crown prosecutors. Most of those cases include offences such as theft, assault or break and enter. Last year, the group received 110 referrals — its most ever — and is on track to meet or exceed that in 2019, according Robinsmith.

Former Coquitlam RCMP officer Bryon Massie “truly embraced that philosophy,” said Robinsmith, and since his departure to become the officer-in-charge of the Chilliwack detachment, others have taken up the mantle, breeding street cops with the understanding that there’s a way to deal with youth crime that doesn't involve the courts and jail.

Police also ramped up their presence in the community following the Niven murder; Coquitlam's first community police station opened seven doors down from the Mac’s a short time later.

Just as CERA has ramped up its work in the Tri-Cities, crime rates across Canada have steadily dropped since their peak in 1991. Critics say our laws are still too soft on minors; others point to the decline in youth incarceration rates as evidence that the justice act has succeeded.

“When we look back, we can see a lot fewer young people per capita in custody than we saw 25 years ago — both adult and youth custody — and we’re not having more youth crime. We’re actually having less,” said Nick Bala, a renowned professor of children, youth and family justice at Queen’s University.

Youth custody rates are affected by more than how hard courts choose to throw the book at minors. Mental health, education policy and the state of the economy all have a massive effect on how many young people commit crimes and end up in prison.

A LEGACY OF CARING

Twenty-five years after The Tri-City News' editorial called for Niven’s murder to have meaning, the legacy of that death can be found in the work of people like Burpee, Sowden and a younger generation that has taken up their causes.

If, back then, the public conversation revolved around youth justice, today it has shifted to drug use and homelessness, and Burpee has followed. In his 11 years helming the Tri-Cities Homelessness and Housing Task Group, he was an instrumental in advocating for the homeless shelter and transition housing units that would be built at 3030 Gordon Ave. in Coquitlam.

When Burpee looks at drug use and homelessness today, he sees the same divide in public opinion that Niven’s murder provoked during the crime wave of the early ’90s — both vast challenges to public policy, both revolving around gathering enough public compassion, and support, to guide people away from cycles of abuse and towards opportunity.

“It takes a lot of time to understand the other side, and if it's not something that's affecting you and your life, people don't see the importance," Burpee said.

“The divide in public interest and perception is very much the same, whether you come from kind of a hardcore, less compassionate point of view or a point of view that recognizes that not everyone has had the same opportunities and not everyone has been exposed to the same abuses in their earlier years.”

When Sowden looks back at Niven’s murder, she also sees the divide that existed, and she’s still struck by how it brought parents from wildly different sides of the same story together to speak as one.

• A note regarding this story: The Tri-City News made attempts to reach out to relatives of Graham Niven but was unsuccessful.

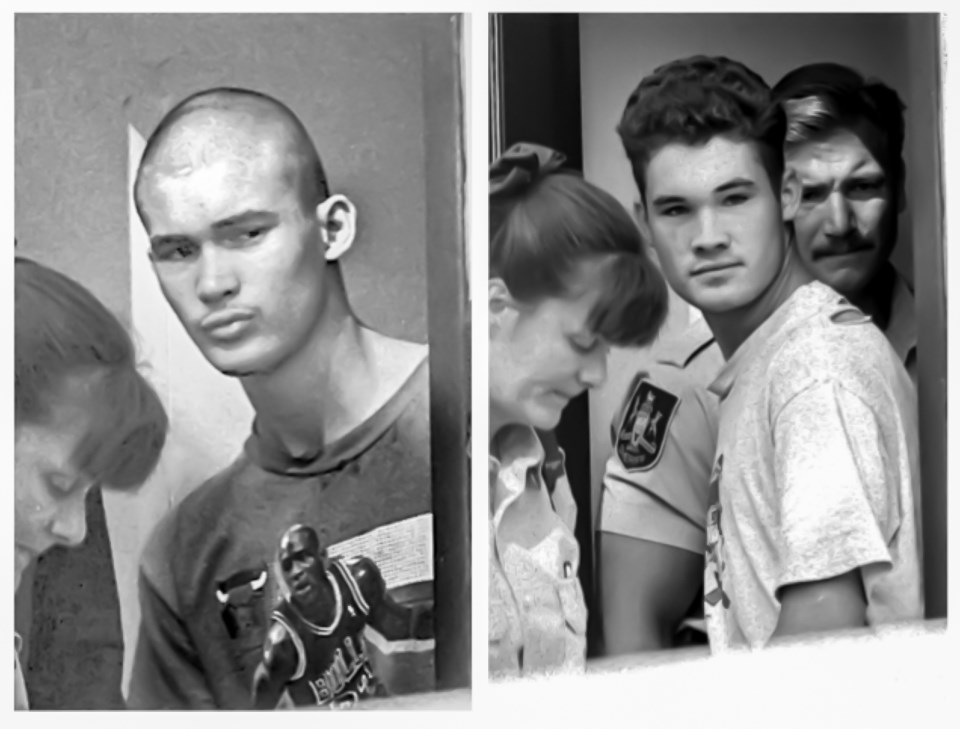

THE KILLERS: WHAT HAPPENED

• Stephen Stark was charged with second-degree murder in 1995 and has been convicted of nine additional offences while in prison, including one case of attempted murder where he cornered another inmate in a courtyard, stabbed him 24 times and kicked him in the face 19 times.

"Violence is well ingrained in your lifestyle," said a 2007 parole board decision reported by the Vancouver Sun. "Your violent acts are planned, calculated and closely related to gang wars within the institution."

In December 2018, The Tri-City News obtained the latest parole board decision, which said that Stark presented a moderate high-risk to violently reoffend. He remains behind bars.

• John Biniaris, 15 at the time of the murder, had come from a healthy family, but quickly spiralled out of control after began using cocaine and drinking alcohol in the lead-up to the night of Graham Niven's killing.

His case was raised to adult court 1996 and his second-degree murder charge was upheld after his appeal was overturned by the Supreme Court of Canada in 2000. He was released from prison on parole in 2001 and, according to Parole Board of Canada decisions obtained by The Tri-City News, refrained from intoxicants for many years, married, upgraded his education and found consistent work in the construction industry.

In a 2014 parole board decision, Biniaris was said “to demonstrate a high level of accountability and stability” and has “exceeded expectations” since being released on full parole in 2001.