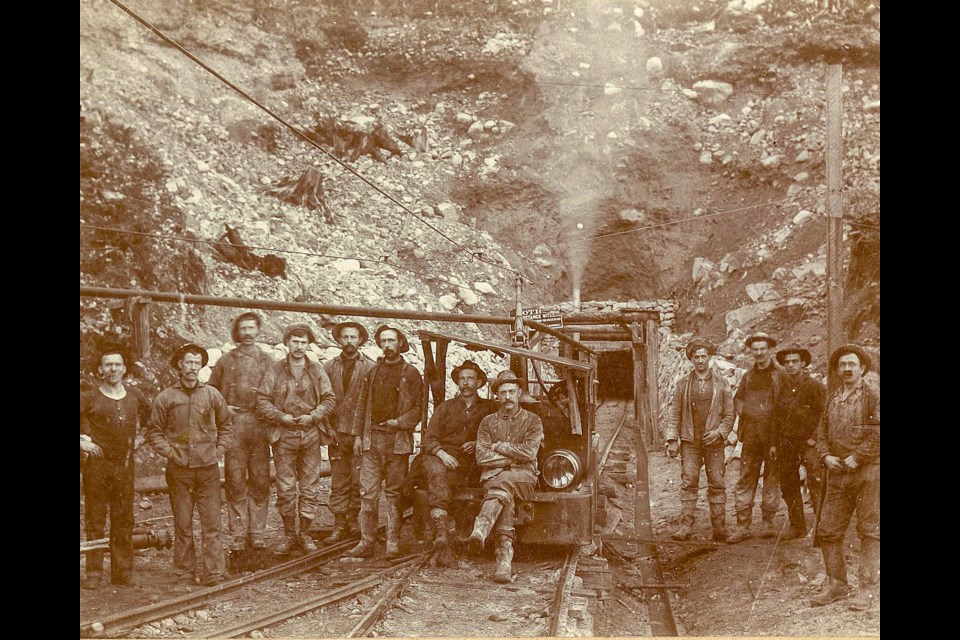

The workers attacked Eagle Mountain from the east and west, blasting through 12,776 feet of granite with steam-powered jackhammers, the shattered stone lugged along rail lines running through nine-foot wide tunnels.

At a handsome 25 cents an hour, they earned their pay, especially when the dangerous, cramped conditions were made especially treacherous by hard patches of blue granite buried up to 1.2 km under the mountain.

Men died and they died in droves, according to historical documents dug up by BC Hydro Pioneers, an organization of retired workers. When workers were killed, company foreman didn’t give them time to mourn, instead forcing them to keep working, writes Will Koop in a 1994 history for the Port Moody Ecological Society.

In all, 103 men were thought to have lost their lives — 53 during the initial construction and another 51 a few years later when it was expanded — their names never recorded, only mentioned in passing through progress reports sent back to the parent company back in England.

It would become the deadliest work project in the history of the Tri-Cities, one of thousands of such sacrifices recognized across the world yesterday, April 28.

Sparked by two Canadians in 1983 who wanted to see miners, lumberjacks and office workers honoured in the same way as fallen firefighters and police, Canada's National Day of Mourning for workers has led 100 countries around the world to follow suite, commemorating the day to workers who were killed, injured or fell ill from their work. It's also become a day to committ to protecting workers and preventing such tragedies from happening again.

By chance, 119 years ago this weekend also marked the moment workers finished the tunnel, linking the southwest shore of Coquitlam Lake to the northeast shore of Buntzen Lake (then two lakes known as Trout Lake and Lake Beautiful), setting the ground work for the first major hydro project in the province.

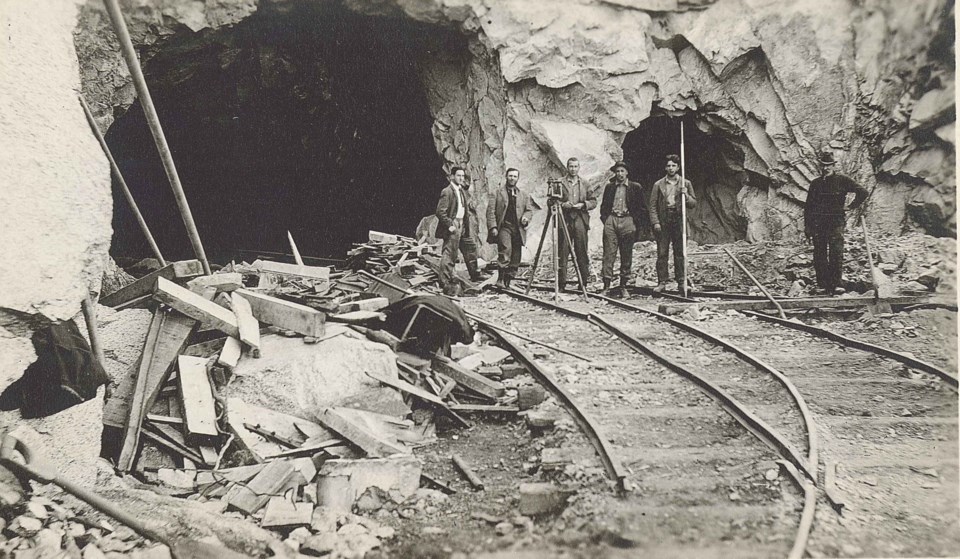

At the time, the project was an ambitious undertaking, and is thought to be the first tunnel of its kind and length constructed in North America. “It was an engineering marvel, an amazing feat,” wrote Koop, noting that when the two ends of the tunnel linked up on April 27, 1905, the error in the line was a mere 7/8 inch.

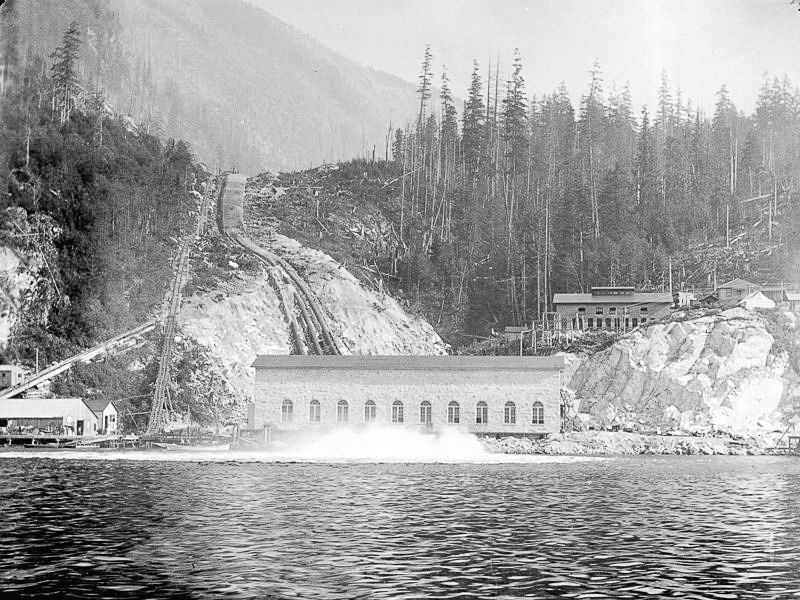

Two months later, 200 guests, including the premier, chief justice, several cabinet ministers, the mayors of three cities, and the most prominent businessmen of the time gathered to see the first rush of water to pour down the tunnel, eventually reaching the newly built 1,500 Kw Power House No. 1 on the shores of the Indian Arm.

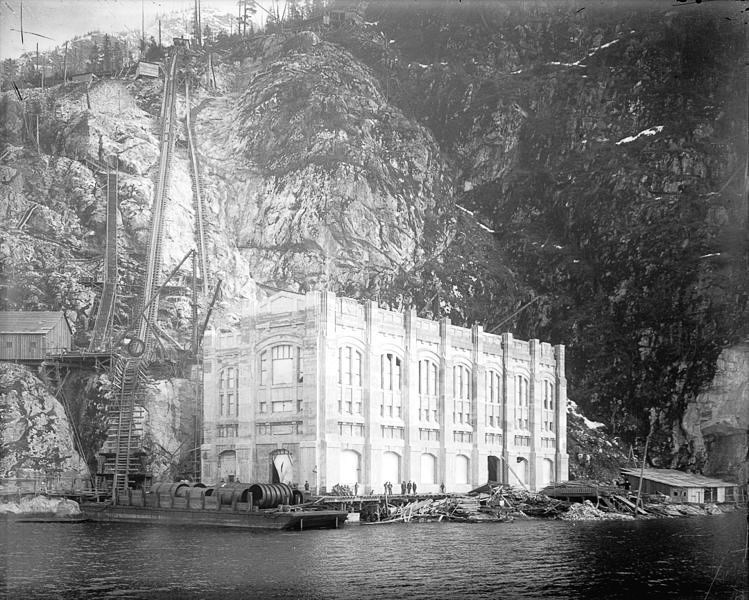

(In 1914, Power House No 2 was built delivering another 26,700 Kw to Metro Vancouver, the fortress-like building eventually playing host to the long list of creepy films, including Lake Placid, Freddy vs. Jason, The Blair Witch Project and a 1990s TV remake of Stephen King’s “It.”)

When in the summer of 1905, the Lieutenant Governor turned on the water with a golden key, it fell 432 feet through the tunnel, from Coquitlam Lake to the newly renamed Buntzen Lake and down a series of tubes to sea level where they would feed the powerhouse.

For the first time, hydro electricity would feed New Westminster’s streetcars instead of steam. Built on the back of over 100 dead workers, the moment marked a massive industrial transformation in the province, and hailed in a new era of industrial-scale hydro power that would reshape the natural environment.

As a June 17, 1905 editorial in The Week: A Provincial Review and Magazine put it a week after the water was turned on:

“The opening of the Lake Beautiful-Coquitlam tunnel last Saturday was, perhaps, a far more important event in the results which are likely to follow than most of those present at the ceremony had any idea of. It marks, we believe, the commencement of a new order of things, which will eventually go far towards revolutionizing industrial conditions in British Columbia. This Province, especially in the Coast districts, has enormous facilities for water power, needing only experience, machinery and the right men to harness them for the use of man. Mr. Buntzen and the Vancouver Power Company have made the first step in this direction on the Provincial seaboard, and made it worthily. Their example will be quickly followed.”