The death of Anne-Marie Nicol’s mother never made sense: How could she die of lung cancer?

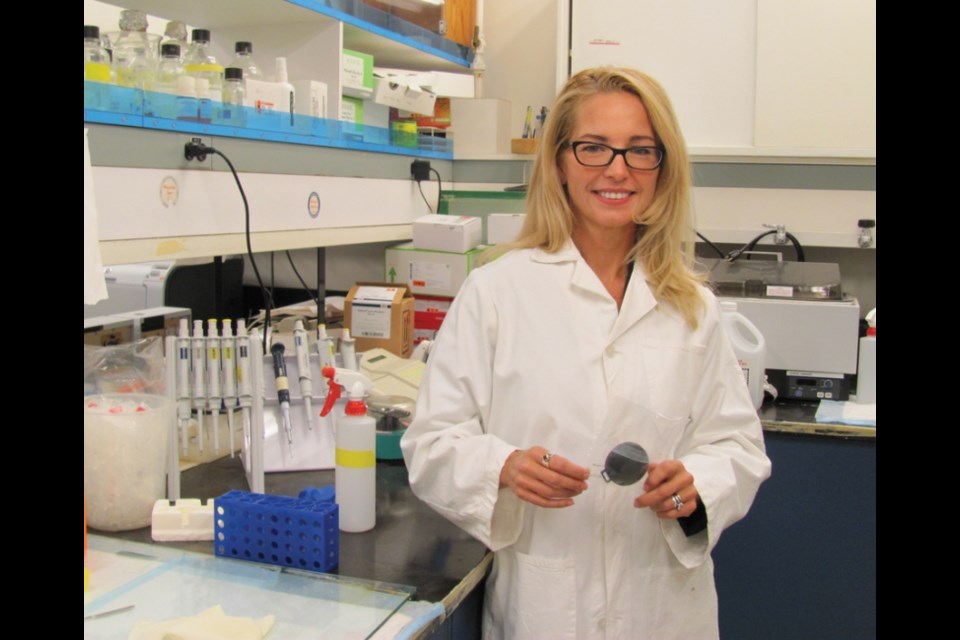

“She'd been a never smoker, a very fit person,” said Nicol, who grew up in Coquitlam and now works as a principal investigator at CareX Canada, an SFU-based group of researchers and specialists focused on reducing environmental exposures to carcinogens across the country.

After Nicol’s mother passed away in 2013, her father sold the home quickly in his grief and Nicol never got the chance to test for any environmental factors that could have triggered her lung cancer. Still, Nicol has her suspicions and her loss has helped focus her work even more.

“We're learning a lot about the other things that contribute to lung cancer besides tobacco,” she said.

One of the main suspects is an invisible, odourless and radioactive gas more than half of Canadians have never heard of: radon.

“It never ceases to amaze me how many people haven't heard about it — and it's the second leading cause of lung cancer, and the first if you don't smoke,” said Nicol.

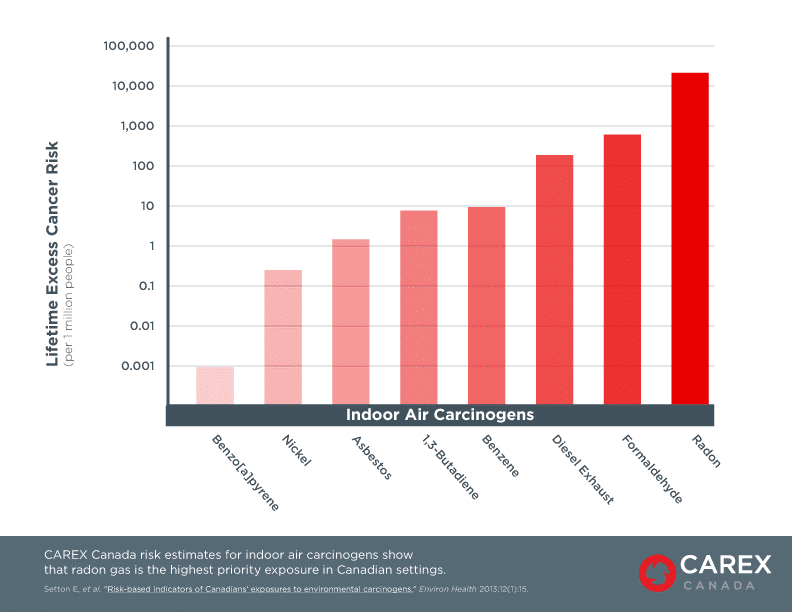

Health Canada estimates radon gas kills roughly 3,200 Canadians a year, more than any other environmental carcinogen after UV radiation, according to one Ontario study.

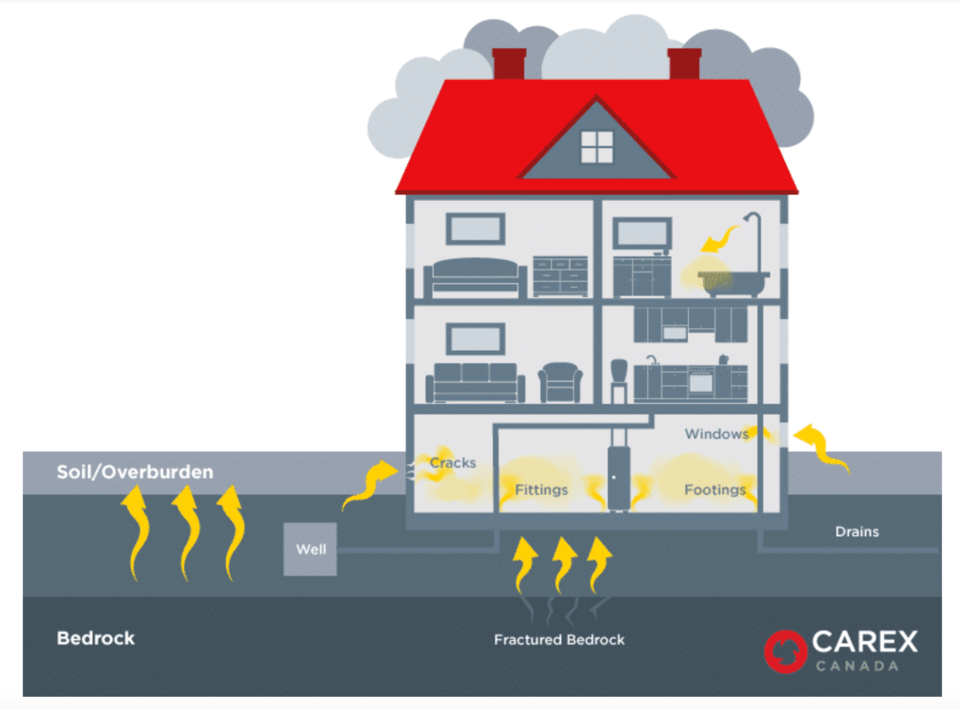

The naturally occurring gas is a product of decaying uranium in the bedrock and soil. Halfway through its lifecycle, the radioactive metal transforms into a gas, which can seep through the cracks, gaps and fissures in a building’s foundations.

Once trapped inside, it’s inhaled into the lungs where the radioactive gas bombards your cells, triggering tumour genesis — the spark that starts the development of cancer.

But predicting where high levels of radon gas are found is a challenge and can vary from province to province, neighbourhood to neighbourhood and even house to house.

TEST OFTEN AND TEST WIDELY

Like the current COVID-19 pandemic, testing for the gas is the only way to know just how widespread a problem it is.

“So when the SFU group suggested they wanted to do the testing, I was like, 'Yeah, we need to know more about Coquitlam,’” said Nicol, who came and spoke to a group of Burke Mountain residents in preparation for testing last fall.

Known as the 100 Test Kit Radon Challenge, last year, communities from across Canada volunteered to add badly needed data points from Abbotsford to Halifax. In total, households from 15 communities took part, including Burke Mountain in Coquitlam.

Of the 113 households that took part in the Coquitlam testing, 2% tested above Health Canada’s guidelines of 200 Becquerels per cubic meter — the unit scientists use to measure radioactivity — and nearly 5% tested in the 100-200 Bq/m3 range, the levels considered dangerous by the World Health Organization.

“That's a good news story for that part of the Tri-Cities,” said Nicol. “But that was only 1% of the dwellings in Coquitlam, let alone the Tri-City region. So there's a lot we still don't know.”

While the more than 100 households that took part in the testing can now breathe easy — or take steps to mitigate the gas — Nicol says, “this is just the beginning.”

The varied geology of the Tri-Cities means that concentrations of radon gas could remain low in one corner and ramp up down the road.

“Health Canada has been banging this drum of getting people to test for a while, but this kind of targeted community-level testing to catch what radon is doing is really getting the ball rolling, getting people engaged and involved,” she said.

Nicol said she hopes the latest round of tests on Burke Mountain act as a call to action, not just by individual community members, but for municipal governments she said can play a pivotal role in raising awareness of the gas.

Unlike asbestos, radon is not limited to older homes. In fact, newer, weather sealed homes may be more energy-efficient, but they can also seal gas in, exacerbating exposure.

“I have a monitor in my house in East Van, and my levels fluctuate all day long, depending on if I open a door, or turn on the oven or turn the heat on,” said Nicol.

That’s because radon gas — like all gas — tends to move away from cold spaces and towards warm ones. As people heat their homes in the winter, warm air rises, creating pockets of low pressure near the ground. In what’s known as a “stack effect,” the gas rushes from the ground to fill the space, passing through cracks and gaps in the foundation.

“Every house is different and you're not going to know until you test,” said Nicol.

BEYOND YOUR HOME

It’s not just people’s private dwellings that are at risk. Radon has been found in public buildings, hospitals and schools.

As the regional representative for the Health Canada supported campaign Take Action on Radon, Nicol has travelled widely across B.C. trying to get community members to pick up the mantle on radon testing.

In recent years, she helped schools across the Sea to Sky corridor test for the gas, leading several to take action to mitigate radon levels. But across B.C., only 8% of schools have tested for radon, a number dwarfed by schools in the Yukon, Saskatchewan and the Maritimes, where radon awareness and testing is much further along.

“In Canada, we don't have regulations to require people to test, for example, child care facilities, which are often in the basement,” said Nicol. “So I've been working with different groups [telling them] why it's important to test for children in particular.”

But like many researchers, the global pandemic has put that work on hold and Nicol has been seconded to work with the B.C. Centre for Disease Control, only like many people over the last six months, her home has become her workplace.

“My home is my gym and my office and my bedroom and my kid is online going to school. We're on Zoom calls and it's like 'Where are you?' 'Oh I'm in my basement.' I'm in my basement too,’” said Nicol.

With COVID-19 cases ramping up and new public health orders increasingly relegating British Columbians to their basements, what better time to test for an indoor radioactive gas?

As Nicol put it, We're going to be grappling with not going back to work for I can't even predict… This is not going away.

• Tests range between $40 and $60 once you factor in the costs of shipping the results off to a lab. Find out more information at here: https://takeactiononradon.ca/where-to-buy-radon-test-kits-in-british-columbia/