Tiana Sharifi has heard the dark stories every parent dreads to hear from their child. Only a few months ago, she was the program director at Children of the Street Society, a Tri-Cities non-profit that spent a quarter century working to keep kids out of human trafficking.

But just as the organization was absorbed by PLEA Community Services as part of an ambitious plan to deliver 300 educational workshops to more than 5,300 children and teenagers, Sharifi struck out on her own, launching Sexual Exploitation Education (SEE) to fill what she sees is the weakest link in preventing sexual predators from reaching children: adults.

Now, she’s taking that message to police forces, parent groups, teachers and counsellors across the province, including SD43, where she has plans to meet with parent and teacher groups.

“Adult education has been lacking,” said Sharifi. “They’re the ones who should be spotting when kids are at risk.”

As sexual exploitation continues to evolve with technology, the line between pimp and online predator has blurred, complicating a fraught digital existence where teenagers and children are already grappling with sexting and revenge porn.

“If we don’t name what’s happening and we can’t see the signs, kids won’t know what’s happening to them. They will think it’s their fault,” she said, pointing to the fact that many young people don’t know that having on their phone naked pictures of someone else under 18 is considered possession of child pornography.

In her new role, Sharifi says she keeps her ear to the ground and regularly receives the latest victim disclosures. Out of that has come a disturbing trend, one where predators are turning to online gaming to contact and groom school-age children.

Take Fortnite, a popular online game where players are thrown into a post-apocalyptic world and tasked with building and defending structures from zombie-like creatures. Like most online games, players have the opportunity to interact with one another, chatting in real-time.

“A lot of these are predators pretending to be younger kids,” said Sharifi. “You have an avatar and you’re in an online fantasy world. It makes it really easy.”

Often, says Sharifi, the chatting moves to another platform like Facebook or Discord, a free video and text chat platform for gamers that has fostered everything from alt-right hate speech to revenge porn.

In what has become an all too common experience, a Grade 6 student from the Tri-Cities was recently targeted through Fortnite by what appears to be an online predator. But when the person on the other end tried to convince the young boy to meet him at a mall — one of many hubs where sexual predators look to meet face-to-face with young boys and girls — he went to his father, an RCMP officer who had taught his son how to spot an online predator.

Most parents aren’t cops tuned in to the latest digital threat to children, however, and it can be hard enough getting a grasp on the latest social media platform, let alone guide your child through gaming chat rooms.

“Parents aren’t aware that they can turn the chat options off,” said Sharifi.

When Sharifi has gone into schools to hear children’s stories, counsellors and teachers are often caught unaware because they don’t know how to spot a predator grooming a kid.

Part of that comes down to regular conversations with children about the kinds of interactions they have online. About 90% of all recruitment starts online and when it comes to prevention, that number is made even more significant by the fact that 75% of children who have been sexually solicited online have not told a parent.

“They don’t know how prevalent it is. Every community, every school you go to, there’s a case of sexual exploitation,” said Sharifi. “If they were to get education on the issue and what it looks like, everyone would get on board. It’s shocking.”

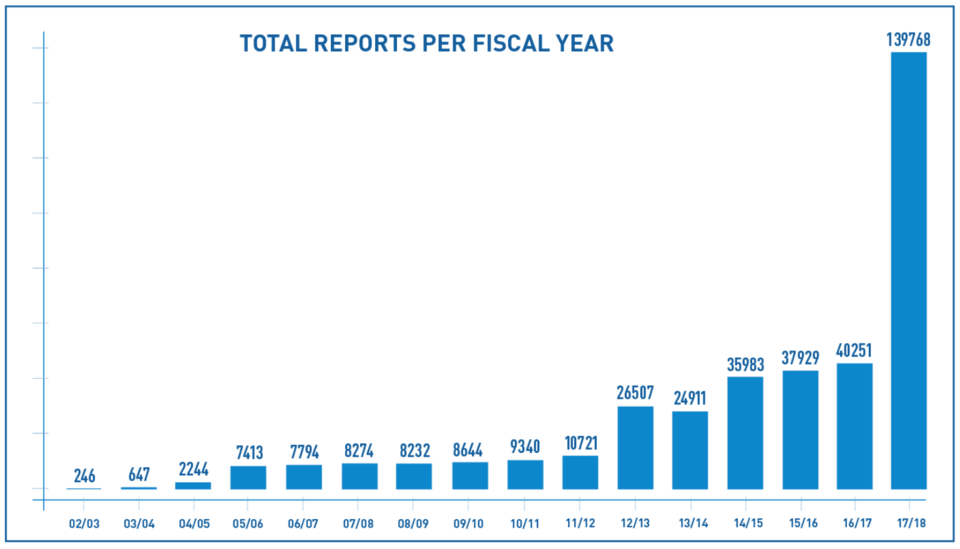

Just as reports of the online sexual exploitation of children more than tripled across Canada between 2017 and ’18, British Columbia is falling behind, says Sharifi. That’s significant in a country that hosts 15% of all websites containing child sexual abuse imagery — the third most frequent national host after the Netherlands and the United States, according to the Internet Watch Foundation.

Across Canada, efforts to fight back have had varied success, and in provinces like Ontario and cities like Edmonton, a lot more funding and resources go into the intervention of exploitation.

“That leads to more focus on communities, families and teachers,” said Sharifi. “I don’t think B.C. has caught up yet.”

Even in the Tri-Cities, where for the last 25 years the presence of a group like Children of the Street Society helped bring community awareness to child exploitation, many — including municipalities — are still coming to grips with the profile and behaviour of a modern sexual predator, Sharifi said.

“It’s not the old creepy man in a van at the park anymore.”