A 54-year-old Port Coquitlam woman wrapped up in B.C.’s biggest immigration fraud investigation — and who was scheduled to be deported — has had her case appealed based on humanitarian grounds.

According to a recently released ruling from the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ou Lian Li's falsified permanent residency application came to light following a Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) investigation into Xun 'Sunny' Wang and two companies he ran under the names New Can Consultants Ltd. and Wellong International Investments Ltd.

When CBSA investigators combed through New Can's offices, they turned up Li's and her husband’s names on several records relating to applications to renew their permanent residency.

The agency discovered Li’s husband, Zhao Qun Zhuo, had lied about his employment status and residence in Canada, and, later, that Li’s travel history and dates of residence in Canada were “tainted with false information,” according to the document.

Xun Wang’s fraud operation was built on helping permanent residents renew residencies or acquire Canadian citizenship by falsely representing the clients’ time in Canada, according to the board's ruling.

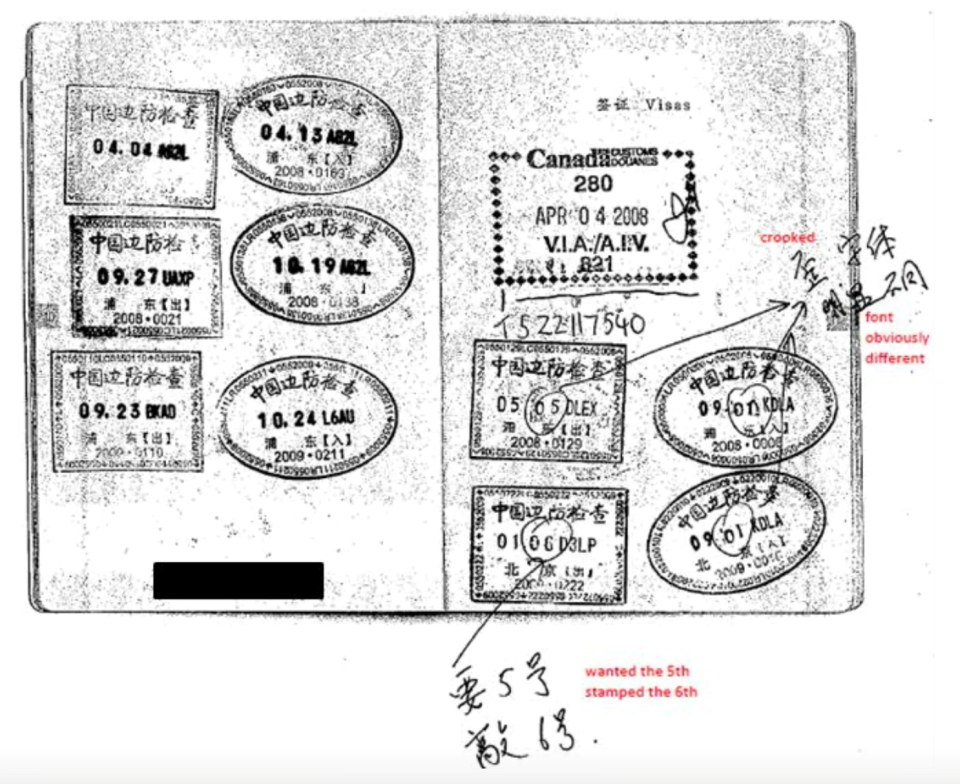

About 1,200 clients paid the company approximately $10 million for its fraudulent services, which included affixing fake stamps to clients' passports; falsely declaring time in Canada on applications; providing fabricated addresses and phone numbers; and providing trumped-up proof of employment by such means as issuing false T4 tax slips.

The ruling paints a portrait of Li's life in Canada and the challenges of getting established as a new immigrant. Li arrived in 2005 with her then 17-year-old son, Vincent. But when her husband quickly discovered he would be unable to find work as an engineer without significant re-certification and local experience, she moved back to China after a month.

Li returned to Canada in 2007 with her son after he had finished high school in China. They planned to stay indefinitely but her mother-in-law got sick and Li once again returned to care for her until her death in 2009.

All the travel meant Li hadn’t spent enough time in Canada to qualify for permanent residency, so following her husband’s suggestion, they sought the fraudulent services of New Can.

“She knew providing Canadian immigration authorities with a false Calgary address 'was not right,' but still, she did not object to her husband’s plan," wrote Leslie Belloc-Pinder on behalf of the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada in its decision. “She signed blank documents, worried about being asked difficult questions about her residence in Calgary, and felt relieved when she was simply handed her renewed PR card knowing it was gained under false pretences.”

Still, Li remained in China for another three years as she worked as an executive in the Sports Bureau to pay off her dead mother-in-law’s medical expenses. In 2013, Li moved back to Canada to be with her son, at which time she started receiving a pension.

In its ruling, the immigration board found Li and her husband’s fraudulent permanent residency applications warranted a removal order, and that the original determination was legally valid.

At the same time, the Immigration Appeals Division, which hears immigration-related appeals, weighed whether Li’s case rose to the bar of humanitarian and compassionate relief.

In the decision, Belloc-Pinder wrote “[Li] and her husband participated in a sophisticated, large-scale, long-term fraud against Canada’s immigration system,” but that Li’s circumstances were but “a tiny part of a larger scheme.”

Despite her decision to go along with her husband’s fraud with New Can — a decision that helps to cast “a cloud of suspicion over other immigrants who gained lawful entry into Canada” — Li’s husband described her participation in the scheme as “innocent.”

And while the board did not believe that Li was fully ignorant of the plan’s impropriety, it did note her role was less serious.

The ruling also found Li was sincere in her remorse. She told the board the idea of leaving China began and never left her back in 1989, a year after her first son’s birth, when she was forced to terminate her second pregnancy due to the country’s one-child policy — a birth control program designed to stem the country’s population growth rate.

Her son had his own son in 2014, a surprise that prompted a profound shift in Li’s life, wrote Belloc-Pinder in the decision. Li immediately stepped in to help care for her new grandson.

In 2019, Li and her husband bought a townhouse in Port Coquitlam, where they now live with their son and his family, which, at the time of the decision, was expecting a second child.

In the ruling, the board wrote, Li’s “transition from professional working woman to grandmother and caregiver is rooted in her family’s support,” and that, should she be removed from Canada, Li’s son and stepdaughter would have to end their studies and quit their jobs to take care of their children.

“Their future plans and economic stability would be seriously jeopardized and it is likely they would have to move from their current residence,” wrote Belloc-Pinder.

The board took special concern with the emotional and psychological effects Li’s absence would have on the grandchildren, notes that she now performs virtually all of the household chores while also holding the role of matriarch. Li’s daughter-in-law testified that their son, Ivan, has “separation anxiety” when he’s away from his grandmother, and that he obeys Li more than his mother.

“If the appellant were removed from Canada at this critical time in this young family’s life and evolution, it would create a significant hardship for them,” wrote Belloc-Pinder.

Despite her role in defrauding the Canadian immigration system, on balance, the board found there were sufficient humanitarian grounds to warrant special relief from the original removal order, and that it was critically important Li continue her role of caregiver for her grandchildren in Canada.