A Port Coquitlam woman and her husband, separated from each other for months, have finally been reunited in a bittersweet visit as B.C. seniors homes begin to crack their doors to family members.

Brigitte Buermann, 80, has spent the entire pandemic in silent wait, dressing up every day and walking to her husband Bernie’s sealed window outside the Hawthorne Seniors Care Community.

Bernie has dementia, and as the pandemic wore on, Buermann feared the lack of family contact would accelerate his deteriorating memory.

“We don’t have much time left,” Beurmann told the Tri-City News at the end of May, separated from her husband by a pane of glass that can’t open.

“I’m afraid he’s going to get to the point where he doesn’t know me anymore.”

Then, like thousands of family members across the province, Buermann got the news that the province would be re-opening seniors homes to family visits.

But those visits came with a list of caveats, and each facility must follow them to a tee. As of July 16, Hawthorne was among 318 seniors homes in the province — less than half of B.C.'s 681 total — that have submitted a plan to the government.

“One has to be very careful during a pandemic with wiggle room,” said Hawthorne’s CEO Lenore Pickering.

“I appreciate how hard it is. But we’re asking our families to understand.”

Only one family member can visit, once a week in 30-minute blocks — though Buermann says she has little more than 15 minutes once you account for the time it takes to disinfect and set up for the next visit.

Pickering said the online registration system has been a real challenge, especially for older family members like Buermann, and her staff have been on the phone for weeks trying to sort out time slots.

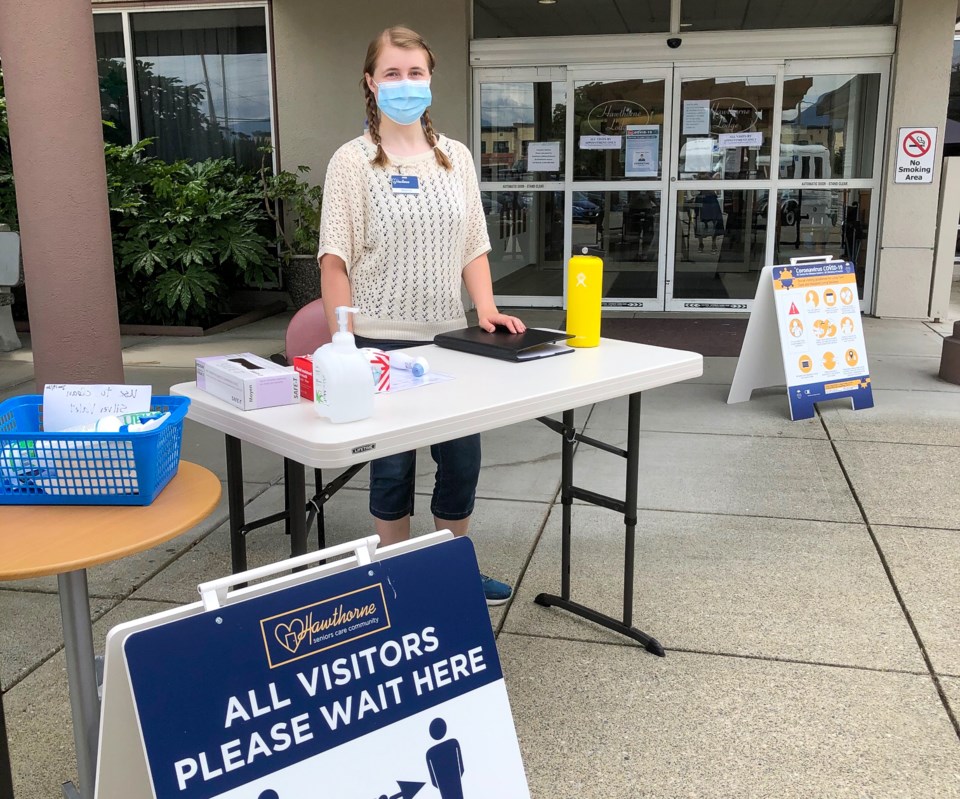

When Buermann arrived at 3:30 p.m. on Monday, a pop-up canopy had been set up near the front entrance. An on-site staff member ensured she had brought her own mask, took her temperature and asked her a battery of health questions, like whether she’d had a cough, fever, muscle aches or a headache.

Buermann was then seated at the far end of a long table and her husband was wheeled out to the other end.

“When they brought him out in a wheelchair, I felt like he was getting wheeled out like a prisoner. ‘You’ve got 15 minutes,’” she said, mimicking the voice of a prison guard.

Buermann talked about her every day, all the while trying to gauge just how much her husband’s mind had slipped away. Bernie was distracted, she said — by the waterfall over there, the blue sky above and a motorcycle buzzing by (Bernie was a motorcycle fanatic).

“It’s the first time. I’m not sure if it went well. It was very sad,” she said. “I hadn’t seen him for a long time. You can’t touch him, you can’t bring him anything.”

Their adult children have not been able to see their father in the same way as Buermann, another frustrating reality as seniors homes walk the line between keeping out the virus and reconnecting with family.

“They can’t even sit on the bench and see their dad,” she said.

The connection between family and resident can mean everything to someone suffering from dementia or Alzheimer’s, and not just at a cerebral level. Dr. Carllin Man, who works at two other seniors homes in Coquitlam, told the Tri-City News that the physical health of his patients with dementia often hinges on contact with family members.

“They’re not just a huge part of a life, they keep them alive,” he said.

Dr. Man said that on one level the slow opening of care homes makes sense.

“First, we’re willing to take a little more risk in general as a society, and now we’re seeing that in the nursing homes.”

But Buermann fears that the province is moving too slowly. Most seniors in long-term care have a life expectancy of fewer than two years. In that period, quality of life can matter as much as how long someone lives.

Before the pandemic, Buermann would regularly go into her husband’s room, bringing him some of his favourite foods, like bananas, German sausages or non-alcohol beer.

“I don’t know if he’s eating enough. I don’t know if he’s got bedsores from sitting too much,” she said. “When you go in, you can show them pictures, you can read to them.”

But now there’s little time and too much distance to read the letters which recently showed up from Bernie’s brother in Germany.

“If I was in there, I’d read to him and he’d sit there with the dog on his lap. Maybe he’d dose off,” she said.

“I miss that.”

But Buermann is also pragmatic. When she looks to the icy sidewalks and chilled air of winter, or at a bump in cases, she worries that even these fleeting visits won’t last.

“It’s scary. Look what’s going on in Kelowna right now. You never know. I’m afraid they’ll be a lockdown again.”

“If I could gown up, I would — I’d go in there.”