Hope for the best, prepare for the worst.

That is a quote and guiding principle written in bold text on the front page of the B.C. government’s 193-page pandemic influenza preparedness plan.

But the plan, which was put together by the province’s public health and infectious disease experts, was not released this month, or this year.

It was published in 2005, with its foundations dating back to 1999.

The grim assumptions back then, when the province’s population in 2005 was estimated at 4.1 million and has since jumped to five million, are all too real today as health officials scramble to contain the global coronavirus outbreak that reached B.C. in January.

The assumption in 2005 was that more than three million people in B.C. would be infected with a virus, the strain of which was not known or predicted at the time of the plan’s publication.

As many as 1.8 million people would become “clinically ill,” up to 610,000 people would visit a health care provider and another 18,500 would need hospital care.

The grimmest estimate: Up to 6,800 people would die from influenza and related complications.

The estimates were not based on a worst-case scenario, but on the impact of the 1957 and 1968 influenza pandemics, which were relatively mild compared to the 1918 pandemic.

Authors of the plan predicted a widespread outbreak of illness would have enormous implications for every sector of society, including front-line health care workers, business and industry, social support agencies and funeral service providers.

“Most experts believe we will have between one and six months between the time an influenza pandemic strain is first identified globally and the time that outbreaks begin in B.C.,” the plan said at the time.

“Within three months from arrival in B.C., we expect that most communities in the province will be affected, and that the impact will continue for six months or more.”

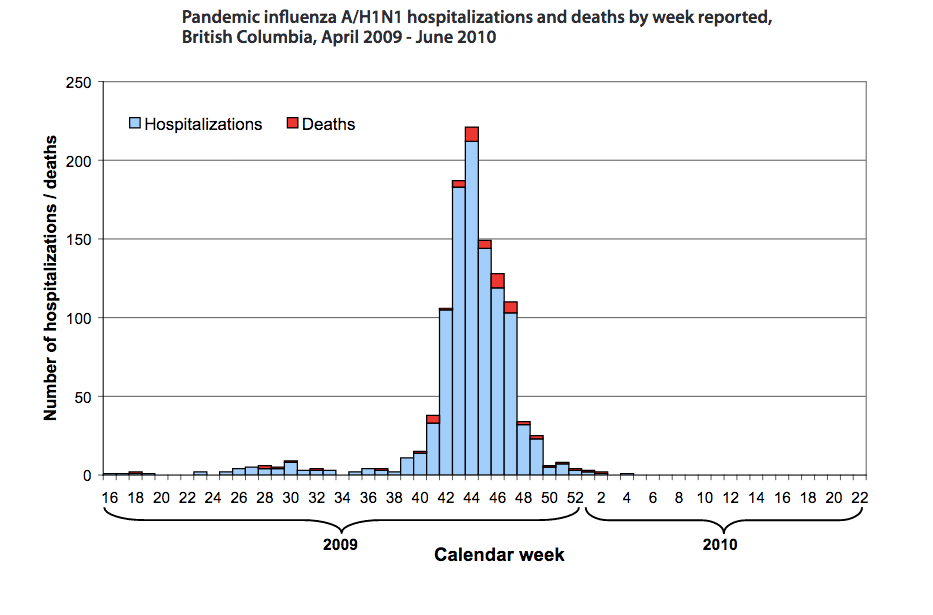

But as B.C. saw in April 2009, with the outbreak of the H1N1 virus, those dire assumptions about infection rates and the gradual shutting down of cities did not occur, although 1,050 people were hospitalized and 57 people died.

The difference?

It was the first pandemic in history where a vaccine was available for a virus while a pandemic was still underway. Effective anti-viral drugs were also distributed and B.C. health officials led a mass immunization campaign.

The coronavirus is not influenza, but a unique virus with unique characteristics, which has set back infectious disease specialists in their mission to quickly develop a vaccine.

It’s a worry for Dr. Perry Kendall, who was provincial health officer in 2005 and oversaw the influenza plan during H1N1 before retiring in 2018. Asked Monday about his greatest concern with the coronavirus outbreak, he said:

“We don’t actually have effective anti-viral drugs at the current time for the coronavirus, and we certainly don’t have a vaccine, and I don’t think we can expect a vaccine in the time it took to develop the H1N1 vaccine.”

Like a fast moving train

As of Monday, the number of people in B.C. who tested positive for the COVID-19 coronavirus reached 103, with that total expected to increase in the days and weeks ahead.

The outbreak has been connected to two seniors’ care homes on the North Shore, Lions Gate Hospital, a dental conference in Vancouver and a downtown bar and restaurant.

Travel has been the source of the majority of infection rates, with B.C. residents and some visitors having returned home from or arrived from China, Iran, Egypt, Mexico, Portugal, the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Seattle, India, Hong Kong and the Philippines.

Some cases were transmitted in the community.

So far, there’s been four deaths, all connected to the Lynn Valley Care Centre. The first death, a male resident in his 80s, was recorded earlier this month. He was, in the lexicon used by health officials, case 27.

The first known case in B.C., which was reported by health officials Jan. 27, involved a man in his 40s, who lives in the Vancouver Coastal Health region.

The man is a regular traveller to China for business and was in Wuhan city before returning home.

Health officials said the man has fully recovered, as have five others who contracted the virus.

Kendall applauded health officials and government for their response to containing the virus, yet noted the speed with which COVID-19 has travelled across the globe, with many countries in lockdown.

“That’s the real difference,” he said, referring to the slower spread of the H1N1 virus in 2009 and the challenge faced by those on the frontlines in 2020.

Though the outbreak and death toll aren’t as severe as other countries, Kendall expected there would be critics of the bold moves made by health officials and governments in recent days.

“My experience is that it doesn’t matter what the illness or condition is, you’re going to be accused of overreacting or underreacting,” Kendall said. “In this particular circumstance, look what’s happening in the U.S., in Washington State, in Italy, in Wuhan, and I would much rather be accused of overreacting than underreacting. The consequences of underreaction are much more severe.”

The rapid pace of the outbreak has been like a fast-moving train, with health officials and government gauging each hour, each day, how to stop it, how to contain it before more people die.

In B.C., health officials have prohibited gatherings of more than 50 people, requested employees work from home and to self-isolate after returning from outside of Canada and get tested if symptoms present themselves.

Their repeated directive for people to regularly wash their hands should be old news by now, as should the need for “social distancing,” a term now widely-used across the globe.

There has also been a consistent call from politicians from all levels of government for people to stop hoarding groceries at supermarkets, a sign of panic among British Columbians faced with an unprecedented and inconvenient reality.

All of it is being done to stop the spread of the disease, or flatten the curve, a term gaining popularity in recent days that is in reference to reducing the upwards curve on a graph that represents a spike in cases.

Even Canada’s Chief Public Health Officer Dr. Theresa Tam is using #FlattenTheCurve in her Twitter updates, as she did Sunday to report cases climbed to more than 300 in the country and warn Canadians “the window to flatten the curve is closing.”

On Monday, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau emerged from self-isolation — a measure he took after his wife Sophie Gregoire tested positive for COVID-19 — to tell Canadians the border would be closed.

But that closure still allows Americans to travel into Canada, a concern raised by B.C.’s Health Minister Adrian Dix, who noted at a news conference Monday the proximity of British Columbia to Washington State, the epicentre of the outbreak in the U.S.

“It’s our strong view and it’s our strong message that visitors from the United States not come to British Columbia,” Dix said. “Don’t come because, at this moment, that is the wrong thing to do. We understand that people are being asked to self-isolate, but better than self-isolate for visitors, is not to come.”

‘Perfection is the enemy of the good’

In Vancouver, Mayor Kennedy Stewart successfully urged health officials Monday to impose an order to prohibit all downtown bars and restaurants from operating on St. Patrick’s Day.

That order came the same day he and city officials announced the closure of community centres, libraries, ice rinks, pools, civic theatres and several other facilities in what was an unprecedented move.

The direction the City of Vancouver has taken follows a trend across the city, where churches have suspended services, businesses have closed, concerts have been cancelled and sports — from recreational leagues to the Vancouver Canucks — are on hold.

Rush hours have lessened, fewer people appear to be taking transit. Ferry sailings are being reduced because of lack of business. The annual 4/20 Cannabis celebration has been shelved.

Casinos have been closed. School classes have been suspended until further notice.

None of this happened during the H1N1 influenza.

In their almost daily media briefings, Provincial Health Officer Dr. Bonnie Henry and Dix have urged people to remain calm, but also warned the outbreak will get worse before it gets better.

“The challenge in the next four weeks dwarf the challenges in the last four weeks,” Dix told reporters last week.

Henry was a member of the Canadian Pandemic Coordinating Committee that responded to the H1N1 outbreak in 2009. Asked Monday what she and others learned from that experience, Henry stressed the importance of setting up an emergency structure in B.C. and across the country to respond quickly and effectively to an outbreak.

“Really, our response nationally and internationally is based on our pandemic influenza response,” she said. “There are so many things that are very similar, there are some things that are quite different. So it has to be adapted and changed. We often say a plan is a basis for change, and that’s what we’ve been doing with this plan. But a lot of what we learned from H1N1 is very applicable to what we’ve been doing in the last nine weeks and will continue to do.”

She pointed out how many young adults ended up in intensive care during the H1N1 outbreak and required ventilators. Those learnings, she said, “are all things that we dusted off and are making sure that we are prepared as we can be for any potential increase in COVID-19.”

Dix said the province has more than 1,200 ventilators and has more on order. In addition, his order Monday to have hospitals postpone all non-urgent schedule surgeries is expected to free up hundreds of hospital beds, although the minister noted only six people with COVID-19 were in hospital.

All others were recovering at home.

Dix summarized a list of “push and attack” strategies to stop the spread of the disease, including setting up a dedicated phone service for the public to call to get questions answered about COVID-19.

An online self-assessment tool is now live.

People requiring re-fills of prescriptions will no longer need a second doctor’s note. Doctors are being provided extra compensation to conduct virtual care services.

All long-term care facilities are being restricted to only essential visitors. A request has gone out to all health regulators to begin emergency registration of non-practising or retired health care professionals, including those in the military.

“Those measures taken together are significant measures both in the acute care system and the primary care system to ensure that we are ready as the situation continues to evolve and develop,” Dix said.

In his opening remarks Monday, the health minister referred to words from Dr. Michael Ryan, the executive director of the World Health Organization’s emergency program, whose speech over the weekend urged governments and health authorities not to be perfect in their approach.

“If you need to be right before you move, you will never win,” Ryan said. “Perfection is the enemy of the good when it comes to emergency management. Speed trumps perfection. And the problem in society we have at the moment is everyone is afraid to make a mistake, everyone is afraid of the consequences of error. But the greatest error is not to move, the greatest error is to be paralyzed by the fear of failure.”

To Ryan’s message, Dix said British Columbians and Canadians “are prepared to fight” and he asked again for all citizens to do the right thing: wash your hands, don’t touch your face, throw away used tissue, stay at home if you’re sick, self-isolate upon return from another country and practise social distancing.

“That is what we are doing in this system, and I think it’s very important that we find our own agency to achieve that goal [to reduce transmission],” he said. “We’re asking all British Columbians to be part of this.”

‘Plan for the worst, hope for the best’

Both Dix and Henry have said since the outbreak that the threat remains low to citizens, despite the escalation in moves by governments and the anxiety that it has triggered in many British Columbians.

“I do think it’s important to say, it’s not inevitable that we are going to get major surges over the next little while,” said Henry, who has been praised by the public for being calm and reasoned in her approach.

“I think we need to be really careful and prepared for it, and it is inevitable that we will see additional cases. But if we’re all doing what we need to do around social isolation, social distancing — making sure we’re doing everything we can in our families and in our communities to stop the transmission of this virus — we can flatten that curve and we can manage.”

As for Kendall, who wrote a report released in June 2010 that commended B.C.’s response to the H1N1 pandemic, he is worried about the speed with which the coronavirus wave continues to roll across the world.

The influenza preparedness plan of 2005 pointed out a pandemic usually has two or more waves, either in the same year or in successive influenza seasons.

The report said a second wave will occur within three to nine months of the initial outbreak and may cause more serious illnesses and deaths than the first.

Will there be a second wave with the coronavirus, if and when the first one subsides?

“I honestly don’t know,” Kendall said. “This is not influenza, this is a coronavirus. We don’t have experience with previous coronavirus pandemics, or severe epidemics to tell us what to look for. So I don’t know, I honestly don’t know.”

Does he still believe the influenza preparedness plan’s guiding principle of “hope for the best, prepare for the worst” applies today?

“I put it the other way around — plan for the worst, hope for the best.”