The First World War could have been opportunity for Canada to do right by its First Nations.

Instead, the federal government stuck with the Indian Act of 1876 that prevented Aboriginal people from attaining the full rights of citizenship unless they renounced their First Nations status.

One of those rights was the right to take up arms for their country.

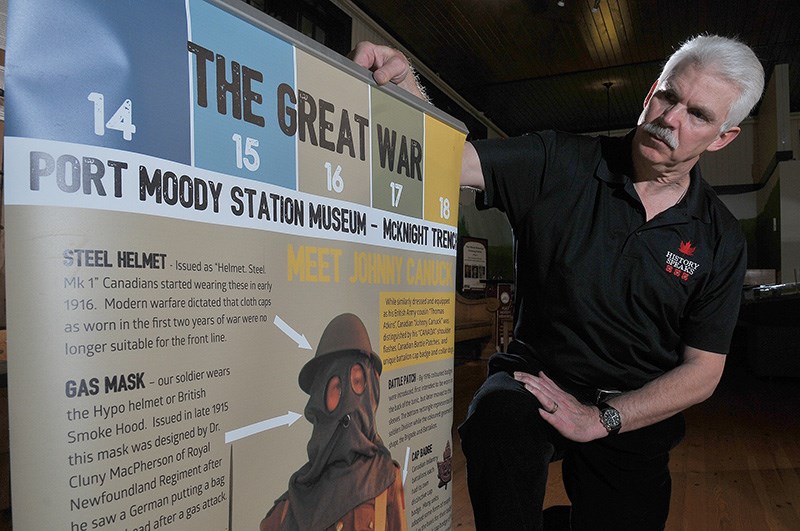

“They were seen as savages or more suited to manual labour,” said North Vancouver historian and author Tom Van Walleghem, who will be giving a talk on First Nations soldiers in the Great War on Sunday at the Port Moody Station Museum as part of its Week of Remembrance.

Nevertheless, some persevered and found a sympathetic recruiting officer who looked the other way as they signed up — or they just lied about their background.

By December 1915, Van Walleghem said, the restrictions were dropped as Canada needed more soldiers.

From 1914 to ’18, more than 4,000 soldiers from the country’s First Nations enlisted — almost a third of their eligible population. Some communities sent every man between the ages of 20 and 35 to the war.

Some of the recruits wanted jobs. Some wanted to continue a tradition of military service started by their ancestors, who fought alongside British troops in the War of 1812, the Seven Years War and the Boer War. Many hoped it would help their cause to become recognized as full-fledged Canadian citizens.

In the trenches of Europe, none of that mattered.

Despite many of them having to overcome language and cultural challenges, First Nations soldiers fought as equals to their brothers in arms. They were valued for their stealth and marksmanship, honed by years of hunting and trapping, that made them ideally suited as reconnaissance scouts and snipers.

One, Francis Pegahmagabow, an Ojibwa from Parry Sound, Ont., recorded more than 300 kills and took more than 300 prisoners. He was one of only 38 Canadian soldiers to be awarded three medals for gallantry.

In total, Indigenous soldiers earned at least 50 decorations for bravery during the First World War.

But, Van Walleghem said, that didn’t do them much good on the home front.

While caucasian soldiers returning home from the war were offered free land to establish farms or low-interest loans to buy equipment to work those farms under the Soldiers Settlement Act, their First Nations counterparts were told the Indian Act still applied and they would have to give up their status to get the benefit. Heroes like Pegahmagabow were dismissed as too wounded or even demented from their time in the trenches to be able to manage a farm.

To add insult to injury, some reserves were plundered of their best land to be turned over to repatriated white soldiers.

“This was our opportunity to bring them into our communities at the same level, and it was missed,” Van Walleghem said.

Instead, efforts to assimilate the Indigenous people continued. Land issues created by the redistribution of valuable farmland still percolate.

“They never got the recognition they deserved as citizens,” Van Walleghem said. “They were still marginalized.”

• Tom Van Walleghem's talk on First Nations soldiers in the Great War runs from 2 to 3 p.m. Nov. 12 at the Port Moody Station Museum, located at 2734 Murray St., next to Rocky Point Park.