The number of people who died in Vancouver over the past five years with “no fixed address” totalled 225, according to data from the Vancouver Police Department.

The deaths that occurred between 2017 and 2021 were recorded by police when they attended “sudden death” calls in the city.

It’s a category that includes overdoses, suicides, workplace accidents and people dying from natural causes.

The data supplied to Vancouver Is Awesome did not include a breakdown of each “no fixed address” death or details on how the person died, where the person died or their gender or age.

Cause of death is determined by the BC Coroners Service.

The most deaths over the five-year period occurred last year, with 65 recorded. That was an increase of 19 people from the 46 who died in 2020. A total of 33 died in 2019, 47 in 2018 and 34 in 2017.

Const. Tania Visintin, a VPD media relations officer, said police attend sudden death calls to determine whether foul play was involved and to gather any other information related to how and why the person died.

“A lot of it is circumstantial,” said Visintin, when asked what types of sudden death calls police regularly attend. “Although the majority of sudden death investigations will be noncriminal in nature, officers are always mindful that a sudden death scene could later become a crime scene.”

Visintin wouldn’t speculate on causes of death for the 225 people, but acknowledged the overdose crisis in Vancouver and across the province has left many vulnerable citizens dead, including some who lived in the now-defunct Oppenheimer and Strathcona park homeless camps.

Police also attend sudden death calls in single-room-occupancy buildings, or SROs, where tenants and guests of tenants with “no fixed address” have died of an overdose.

Data collected by police between February 2017 and Sept. 5, 2021 revealed that 50 per cent of suspected overdose deaths in the city occurred in SROs and in other low-income housing.

419 overdose deaths in Vancouver

The Coroners Service’s most recent data on illicit drug deaths in B.C. showed that 1,782 people died of an overdose in the province between January and October of last year, with 419 recorded in Vancouver.

The Coroners Service last published a report on province-wide homeless deaths four years ago, with an updated version anticipated within the next month, according to Ryan Panton, manager of strategic communications and media relations for the Coroners Service.

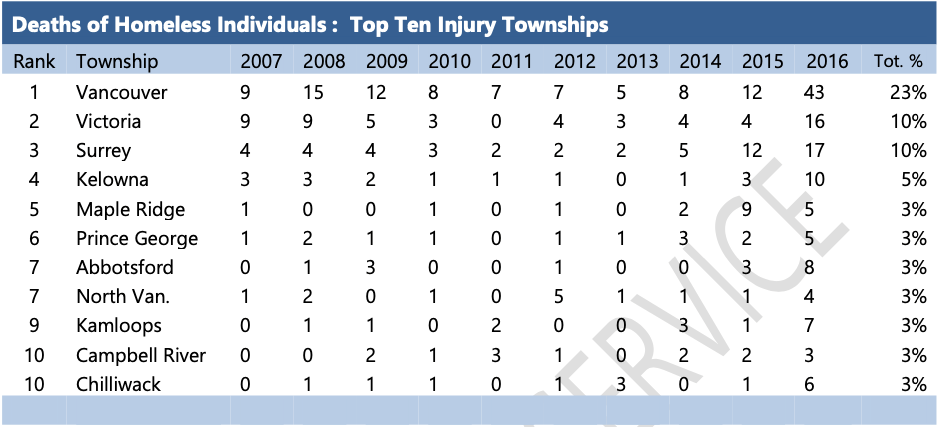

The 2019 report, which summarized deaths between 2007 and 2016, said an average of 55 homeless people per year died in B.C., with 175 deaths in 2016 being the worst year on record; there were 73 recorded in 2015.

In Vancouver, 43 homeless people died in 2016, almost tripling the nine-year high of 15 recorded in 2008, according to the agency, which concluded that 56 per cent of all homeless deaths in B.C. were deemed accidental, with 72 per cent involving drugs, alcohol, or both.

Deceased were included in the calculations if “no fixed address” was given as the home address, or if the person died at a homeless shelter, or if “the circumstances of death suggested homelessness,” according to the report, which included people found dead in parked vehicles.

The report cautioned that it is not always possible to determine a person’s housing status.

“As such, data may be under-reported,” the report said.

Public health emergency

The data in both Coroners Service reports that provides the most telling insight into the growing number of homeless and drug deaths is what was recorded in 2016.

That is when 86 per cent of accidental deaths and 53 per cent of all deaths resulted from “unintentional drug and/or alcohol poisoning.”

In the period between 2007 and 2015, the same category accounted for 63 per cent of accidental deaths and 34 per cent of all deaths on average.

It was also in 2016 when Vancouver and other cities in B.C. saw significant spikes in overdose deaths, with Vancouver increasing from 138 in 2015 to 231 in 2016. Surrey increased from 76 to 118 and Victoria went from 23 to 68.

All three cities have seen their death tolls almost double since 2016, the year that then-provincial health officer Dr. Perry Kendall declared a public health emergency — and two years previous to the Insite supervised injection site on East Hastings recording an unusually high number of overdoses.

At the time, Vancouver police rushed a sample of the drug being used in the area of Insite to a Health Canada lab and determined the presence of fentanyl, which has been linked to more than 80 per cent of overdose deaths in B.C.

'No excuse for not doing that'

COPE Coun. Jean Swanson, whose focus in her first term at city hall has been to push for more housing and services for homeless people, said Monday she wasn’t surprised by the number of citizens with no fixed address who died in Vancouver in the past five years.

Swanson pointed to pandemic-triggered public health orders related to physical distancing, strict no-guest policies in SROs and less space in shelters coupled with a toxic drug supply as likely reasons for the number of deaths.

She said the police data serves as another reminder that there’s not enough housing for low-income people, particularly those living with a mental illness, or severely addicted to substances, or both.

“We need safe supply, we need housing and governments have no excuse for not doing that,” she said.

A memo from staff at city hall to council in November suggested the rate of homelessness in Vancouver “remains the same or perhaps may have even increased” since March 2020, when volunteers counted 1,548 people living in some form of shelter and 547 on the street.

Some other findings of the Coroners Service’s 2019 homeless deaths report:

• Of the deceased, 53 per cent met the criteria for “street homelessness” and 36 per cent for sheltered homelessness. Males were more likely than females to meet criteria for street homelessness (55 per cent vs 40 per cent).

• Overall, 85 per cent of those who died were male. The percentage of females trended downwards with age. The highest proportion of females was in the 30 to 39-year-old age group (27 per cent), and the lowest in the 60-plus age group.

• A total of 54 per cent of the deceased were aged 40 to 59.

• Deaths occurred more often in the later months of the year. From August to December, the average number of deaths per month was 60. From January to July, it was 36.

• Together, Fraser Health and Vancouver Coastal Health accounted for 59 per cent of the deaths from 2007 to 2016.

@Howellings