A memo obtained by Glacier Media that was emailed Monday to city council and staff cited challenges related to social distancing, concerns about transmission of COVID-19 and mobilizing several hundred volunteers as reasons for cancellation.

“As a result of public health orders related to the pandemic, the training and deployment of volunteers and activities related to carrying out the count this March is not possible,” said the memo from Sandra Singh, the city's general manager of arts, culture and community services.

Singh said staff will instead collect alternate sources of data “to paint a picture of homelessness” in Vancouver, which has had a homeless population that has hovered around 2,000 people for the past four years.

The city’s new approach will include:

• Collecting occupancy data from shelters, no fixed address (NFA) data from the Vancouver Police Department and health authorities in a similar manner to the homeless count methodology.

• Collecting NFA income assistance data from the Ministry of Social Development and Income Assistance. This will show how many people on income assistance are listed as currently experiencing homelessness.

• Conducting an online survey with outreach service providers for an update on “street homelessness.”

• Conducting an analysis of the 2020 Homeless Count data to create profiles to better understand the experiences of Indigenous and Black people, who are overrepresented in homeless counts.

• Synthesizing and analyzing available data that is captured by different city, provincial and community sources related to homelessness.

A homeless person in Vancouver. File photo Dan Toulgoet

A homeless person in Vancouver. File photo Dan ToulgoetCoun. Jean Swanson, whose primary focus since elected in 2018 has been to get people off the street, had mixed feelings about the count being cancelled this year.

“I’m not too disturbed about it because everybody knows homelessness has gone up [since last year’s count], everybody knows there’s a high percentage of Indigenous homeless people,” Swanson said. “I don’t think it’s going to lessen the urgency of the problem by not having a count.”

Swanson said the city can count homeless people “until hell freezes over,” but until more housing is provided and supports are in place to help people, homelessness will continue to be an issue in Vancouver and the region.

The city has led or participated in homeless counts in Vancouver and the region since 2005. In recent years, volunteers have surveyed people who have agreed to give more details about their life and how they became homeless.

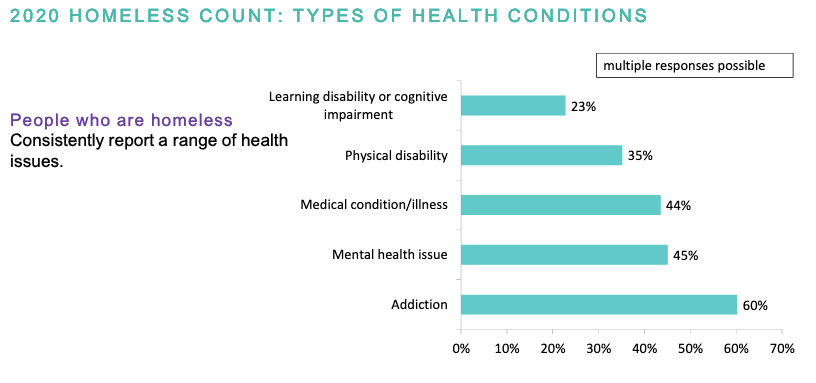

Survey results have provided the city with information where a person last paid rent, their health conditions, sources of income, whether they have mental health or addiction challenges and whether they are a Canadian veteran.

City officials have always cautioned the counts have provided only a 24-hour snapshot of homelessness in Vancouver and the exercise is likely an undercount of the true number of people in the city without a home.

Even so, data from the counts and profiles of homeless people has been used to inform city policies and the municipal government’s requests of the provincial and federal governments for funding to combat homelessness.

“Everyone’s journey into and through homelessness is unique and first-person accounts about the pandemic’s impact on people experiencing homelessness will not be directly captured in this alternative approach,” Singh said.

“Unfortunately, this is an unprecedented time and the COVID transmission safety concerns and following public health direction prevent the necessary training and deployment of 500 volunteers across Vancouver to conduct in-person interviews with over 1,000 people experiencing homelessness.”

Findings from the region's 2020 homeless count related to Vancouver. Image courtesy City of Vancouver

Findings from the region's 2020 homeless count related to Vancouver. Image courtesy City of VancouverA count conducted across the region in March 2020, which occurred prior to the pandemic being declared, showed that Vancouver saw a slight drop in the number of people living without a home — 2,095, compared to 2,223 counted in March 2019.

A report released by the B.C. Non-Profit Housing Association showed that 1,548 people lived in some form of shelter at the time of the count and 547 resided on the street. The count was conducted over 24 hours on March 3 and 4, 2020.

Vancouver made up the bulk of the homeless population counted in the region, with a total of 3,634 people spread across 11 municipalities. Volunteers counted 644 homeless people in Surrey, 209 in Langley, 124 in Burnaby and 123 in New Westminster.

Other municipalities involved in the count were North Shore (121), Ridge-Meadows (114), Tri-Cities (86), Richmond (85), Delta (17) and White Rock (16). When totaled up, the statistics show an overall increase of 29 people from the last regional count conducted in 2017.

In debate last fall at Vancouver council over homelessness, city staff estimated the number of people living on the street had increased by at least 200 people since the count in March 2020 for a total of 750 “street homeless.”

Some of the factors that contributed to the increase are outlined in Singh’s memo.

They include:

• The implementation of “no guest” policies at some single-room-occupancy hotels, supportive housing units and affordable housing buildings impacted “couch surfers” and forced many to resort to street homelessness.

• Many day respite spaces such as community centres, libraries and outreach drop-in programs had to temporarily close or significantly limit their occupancy and usage, particularly hygiene and washroom access.

• Shelter occupancy levels were lowered to comply with physical distancing requirements, as per public health mandates.

• Some low-cost housing operators temporarily suspended new tenant intakes at the beginning of the pandemic.

• Changes to the operation models of many outreach providers and meal service providers to comply with safety regulations for staff and clients. This often included limited services and an increased difficulty in accessing food for individuals in need.

• Social isolation for people living alone, in single-room-occupancy hotels, including seniors, people with disabilities and chronic health conditions.

Green Party Coun. Pete Fry. File photo Dan Toulgoet

Green Party Coun. Pete Fry. File photo Dan ToulgoetCoun. Pete Fry said he declined to participate as a volunteer in last year’s count because of concerns related to the transmission of COVID-19. Fry suggested alternate methods of data collection this year “may actually turn out to be, at the end of the day, a more accurate reflection” of the city’s homeless population.

“Perhaps we do return to this point-in-time count as one of a suite of tools that are being used, but digging into some of these other data streams is probably going to be super helpful in getting a better rounded estimate and assessment of the people who are unhoused in the city,” Fry said.

Counts in Vancouver have shown the homeless population has steadily increased in Vancouver since 2015, when 1,746 people were recorded. That population grew to 2,138 in 2017 and 2,181 in 2018.

The 2020 count data showed again that Indigenous people are overrepresented, with 33 per cent of those surveyed identifying as Indigenous. The 2016 census says Indigenous people make up 2.5 per cent of the overall population.

Last year’s regional count introduced a question in the survey to capture a person’s racial identity. The question was added to better understand how racialized groups are impacted by homelessness.

A total of 98 people identified as Black, representing six per cent of a racialized group that represents only 1.2 per cent of the general population in the region. South Asian and Latin American people both represented three per cent of the homeless people surveyed.

Caucasian people represented 79 per cent of homeless people surveyed.

That count was done when the Oppenheimer Park tent city continued to operate — until the park was cleared in April and May — and after the current encampment at Strathcona Park was set up in June 2020.

City council and the public should learn in September 2021 what the results are of the city’s new approach to tracking homeless people and their needs.

@Howellings