In the 2007 film Ocean’s Thirteen, a cast of characters plot an elaborate casino heist. One pretends to be a real estate tycoon to gain special access. “Look, he owns all the air south of Beijing,” his pretend assistant tells an inquisitive casino employee. “Try building something larger than three storeys in the Tianjin province and see if his name comes up in your database then.”

Though comedic, the scene alludes to a serious question: Who, if anyone, can “own” air space? As Vancouver densifies, the answer to this question is increasingly pertinent to developers and property owners.

“In general in B.C., when one owns a piece of land—and by a piece of land I mean the ground—you own the airspace above it and you own the subsurface below it,” said Allyson Baker, associate counsel with Clark Wilson LLP.

“But that is subject to various statutes in B.C., and it’s also subject to the common law. Generally, the expectation is, if you own the land, you own the airspace above it to a reasonable level to reflect what your uses of the property are.”

It quickly gets complicated. A construction crane might swivel over a property, or drones may pass overhead. There are also billboards, telecommunications equipment, SkyTrain tracks, bridges, overpasses and foliage to consider.

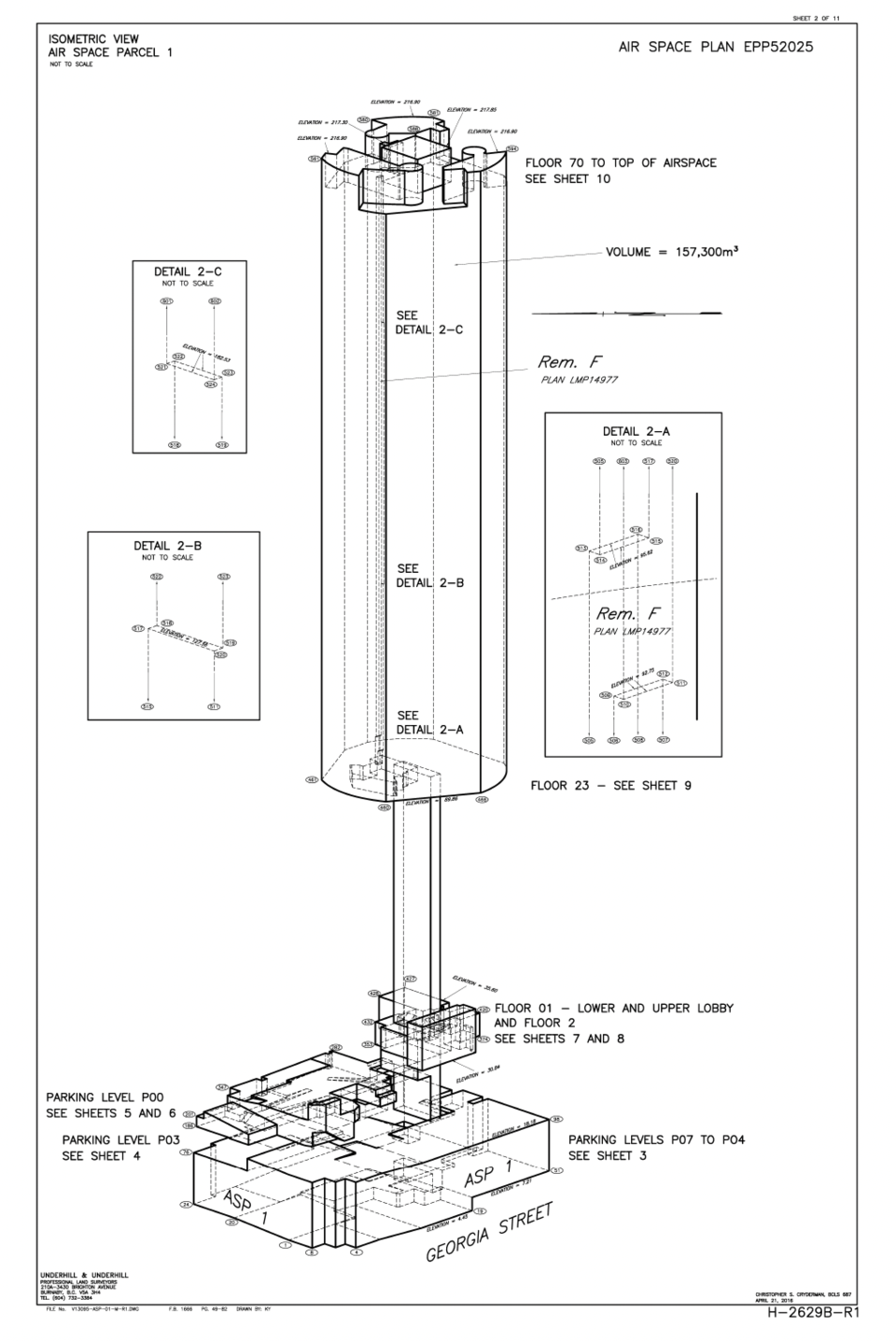

To help govern such scenarios—which may be addressed in regulations or can be resolved through negotiated agreements—B.C. allows for the creation of “airspace parcels,” which are invisible 3D columns that exist above a 2D piece of land. Parcels can then be sliced and diced into distinct pieces owned and used by different parties.

“It’s rarely as simple as just straight horizontal lines,” said Baker. “Developers can be really creative when it comes to developing an airspace parcel arrangement. The pieces sometimes end up looking like different-coloured LEGO being put together within it.”

When an airspace parcel is created, so too is a residual parcel called the “remainder.” Whoever owns the remainder owns the airspace above the development.

Baker compares this to the game Jenga.

“An airspace parcel is like taking one of those little blocks out, and what’s left behind in that tower is the remainder, although it’s often land,” she said.

Whereas strata plans create strata lots, airspace parcels are different in that they create subdivided lots, said Bradley Cronquist, partner with Kelowna-based Pushor Mitchell LLP. Each subdivided lot can be further subdivided, and can have its own strata corporation.

A single downtown development can have more than half a dozen airspace parcels and multiple strata corporations.

“When you do airspace parcels, basically you’re subdividing a cube of air, so it’s not two-dimensional, it’s three-dimensional and it creates a separate lot,” Cronquist said.

Airspace parcels increasingly popular for mixed-use developments

Airspace parcels are increasingly being created for mixed-use developments with different components, like retail on the ground floor with office, hotel and residential uses above. This enables each component to be separately owned, governed and financed, Cronquist said.

“Some people don’t like owning commercial versus residential, and vice versa,” he said. “So if you have residential in one strata corporation and commercial in a different strata corporation, you completely separate them.”

This structure also allows for multiple lenders, he added.

But what about common needs across parcels, such as heating and cooling, water, sewer, electrical, elevators, fire suppression, structural supports, loading bays and emergency access?

Agreements between all parcel owners are needed because the Land Title Act has few provisions about airspace parcel arrangements. These agreements are sometimes called “airspace parcel agreements” or “reciprocal easement agreements,” said Baker.

“Really what they are is an easement, and what they do is they set out how the whole arrangement is going to function from an access perspective, from a services perspective, and they do include other provisions such as obtaining insurance on the building.”

Such agreements can also provide for cost-sharing, such as if an emergency generator breaks down and needs to be repaired. The agreements are filed in the land title office and will show up on the title to each airspace lot.

“You’ll see covenants on title that can be 30-40 pages long that are required by the city as a condition of approving the airspace parcel subdivision,” said Cronquist.

Single-family homeowners who wish to transform their homes into fourplexes, for example, need not concern themselves with airspace. You probably wouldn’t do airspace, but instead you would register a strata plan and create four different strata lots.

Story continues below image

Airspace might still be possible above detached homes.

“That’ll be subject to zoning with the applicable municipality, whether the municipality would allow them to subdivide the land in order to create an airspace parcel,” said Baker.

A city’s considerations would likely include the neighbourhood or community plan, she said, which would give developers and their consultants an idea of what’s possible on a given site.

“If you think of the airspace parcel regime, it’s sort of a tool in the toolbox to address, fundamentally, subdivision issues and disconnects between ownership, or recognizing that different owners need to exist in the same building in different asset classes and different financing classes,” said Matthew Tolan, partner with Borden Ladner Gervais LLP.

Is airspace in Vancouver becoming more valuable and coveted as the city grows taller?

“I think the value’s driven by the city and the city zoning,” said Tolan.

“Is airspace at a height of 1,000 feet above the city going to be valuable? Not yet. I think the city’s pretty clear that it doesn’t want to build that high. But is it valuable in Dubai? It certainly is.”