A top United States government official says there are plenty of issues to keep like-minded Arctic nations together after Russia's invasion of Ukraine forced seven of them to pause their participation in the international body that looks after the region.

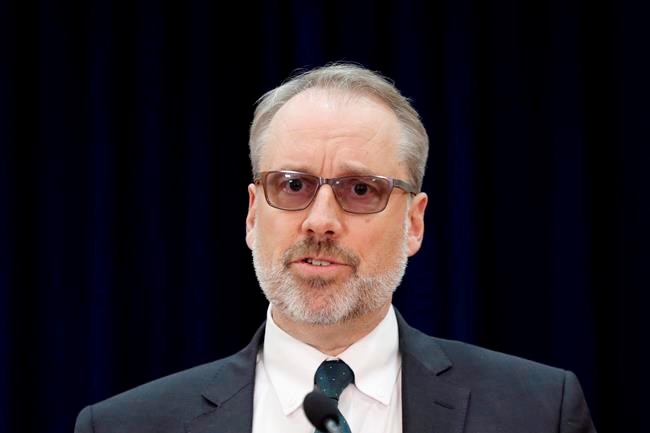

But U.S. Co-ordinator for the Arctic Region James DeHart says there's no clear path forward for the Arctic Council of old. All of its members refused last week to work with Russia.

"I don't know if I can give a compelling answer to that," DeHart said in an interview with The Canadian Press Monday. "We will use this pause to figure out how we can proceed.

"We don't know where this is going to go."

DeHart is the diplomat responsible for co-ordinating American policy in the Arctic and working with its allies there. He is making his first visit to Canada, which comes the week after the U.S., Canada, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark and Iceland all agreed to step away from the Arctic Council, currently being led by Russia.

It wasn't a hard call, DeHart said.

"It came out of everybody's revulsion at what we're seeing," he said. "Consensus was quite easy to come by."

Russian officials in London told the Reuters news agency that the decision was "regrettable" and would "inevitably lead to the accumulation of the risks and challenges to soft security in the region."

The Arctic Council, formed of the countries that ring the North Pole, is a major sponsor of scientific research and has led to important treaties on pollution prevention and maritime safety. There are still plenty of opportunities for research between council members, as climate change and the ongoing opening of the Arctic won't stop, DeHart said.

The council doesn't deal with security issues, which makes threading a path through the current war in Ukraine tricky.

"We want to avoid damage to the council," said DeHart. "We don't want to insert discussions of military issues."

DeHart sees little risk of the Ukraine conflict spreading to the Arctic, although he acknowledged Russia's military has been increasingly assertive in the area for years.

Cold War-era military bases have been reactivated and Russian military aircraft are creeping up western airspace. In one recent NATO exercise, Russians jammed GPS signals that affected civilian activity, DeHart said.

"Long before we had seen Russia's further invasion of Ukraine, we had seen Russian build up its old military infrastructure in its part of the Arctic," said DeHart.

Global Affairs Canada did not immediately respond to a request for the federal government's view of the council and its future.

In a statement, the Inuit Circumpolar Council -- one of several Indigenous groups that are permanent participants on the Arctic Council -- said it supported the seven nations stepping away from the group.

"(The council) is monitoring the situation closely and agrees with the (senior Arctic officials)," it said a statement.

Meanwhile, Canada and the U.S. have plenty non-council items on their northern plate to talk about.

Issues include updating and modernizing the early-warning system the two countries use to monitor their airspace. DeHart also wants to talk about critical minerals such as lithium — a crucial component in modern batteries found in several deposits in the Northwest Territories.

Salvaging the old idea of the Arctic as a zone of international peace and co-operation won't be easy, said DeHart. But diplomats will try.

"The fundamental goal here does remain the same — to keep the Arctic a region of peace."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published March 7, 2022.

— Follow Bob Weber on Twitter at @row1960

Bob Weber, The Canadian Press