Dennis Marchant celebrated his 40th birthday recently with three steaks and half an ice cream cake.

He earned them.

Earlier this month, the Coquitlam accountant finished 35th in the Moab 240 ultramarathon in Utah. In 86 hours, 58 minutes and 50 seconds, he covered 243 miles of road and rugged trails, traversed two mountain ranges, skirted a snowstorm and got annoyed when he kept having to run around his wife and two kids playing ping pong on one long stretch of the route.

The latter was a hallucination, one of the recreational hazards of ultramarathoning, where runners test the limits of their physical and mental endurance over hundreds of miles of trails with little or no sleep. Or, as Marchant likes to call it, his birthday present to himself.

Marchant started running in grade school, mostly 100-yard dashes. When he was in high school he trained for his first 10 km Sun Run and progressed up the distances to half and full marathons from there.

Then he got bored.

It was while training on the Grouse Grind Marchant learned of the Knee Knacker, a renowned 50 km trail race across the North Shore mountains. He signed up and regretted it almost immediately.

At the foot of Mt. Seymour, just past the last aid station yet still far from the finish at the top of the mountain, Marchant was, well, knackered. He didn’t think he could go on, but he couldn’t drop out either.

“That was the only time I ever actually cried,” he said.

Marchant finished the race just before the time cutoff, but the experience lit within him a new competitive fire for long-distance trail running.

In the 10 years since, Marchant’s completed several ultramarathons of varying distances, including the 120-mile Fat Dog in Manning Park, which is considered one of the toughest ultramarathons in the world, according to Outside Online.

Marchant said while he relishes the physical test of running such long distances, it’s the mental toil that attracts him to finding new, longer races to conquer. And few are as daunting as the Moab 240, which is part of the Destination Trail triple crown of endurance races that also includes 200-mile events in Lake Tahoe, CA., and Mount St. Helens in Washington State.

In fact, the Moab race almost broke Marchant’s spirit on its first day, he said.

The weather was warm and dry, the terrain flat, but Marchant said he was discouraged when runner after runner in the field of more than 150 registered participants from around the world kept passing him. He had to fight through growing doubts about his strategy to stick to a manageable pace of 3 mph. He had to resist the comforting temptations of the Hamburger Rock aid station that he described as an amalgam of a party and a war field hospital.

“It’s just so tempting to get sucked in,” he said of the stop, where there was food, warm beverages, medical aid, massages and cots to sleep on.

Marchant, who ran with all his gear for running at night and in cold weather packed into a backpack because he had no support team, pressed on. He said he didn’t want to disappoint his family and friends, but mostly himself.

“I knew my plan was the right one,” he said.

After a cold, lonely night running in isolation with only the light from his headlamp to guide him, Marchant started passing other runners who had bolted ahead of him in the race’s opening hours.

“I could see how my place was improving,” he said. “It’s motivating, and then things start to snowball.”

As a runner’s time for ultra-marathons is cumulative from the start, including stops for aid, fuel and sleep, Marchant slept only 2.5 hours over the course of the nearly four days. He said that kind of sleep deprivation can play with your mind,

Hence the odd hallucinations of his family’s ping pong game — he doesn’t even own a ping pong table.

“I got pissed off that I’d have to run around them,” he said.

When delirium happens, Marchant said it’s important to engage another runner in conversation to jolt back to reality — not an easy feat when participants are scattered along hundreds of square miles of rugged terrain.

Marchant’s steady pace got him to the finish almost a day ahead of his anticipated finish. Which presented another challenge — he had no place to sleep as he’d booked a cabin for the next day. Fortunately, one of the race directors had a spare sleeping bag and was able to find him a vacant tent.

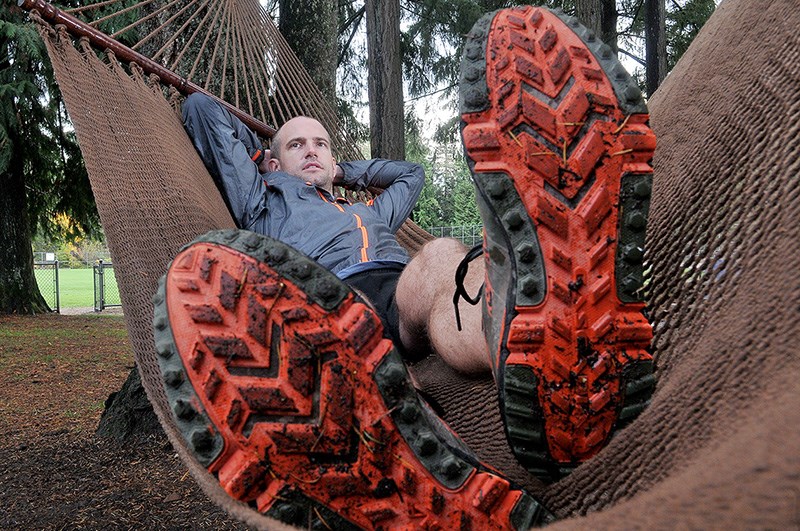

Marchant used only one pair of shoes in the race, but the event took a toll on his feet — he had to speed walk the last 40 miles because of pain and he’s not sure when he might regain feeling in the end of his toes.

But that hasn’t deterred Marchant from eyeing his next challenge. He’s heard rumours of a new 500-mile race being organized.

“The challenge of pushing yourself to the limit, that’s my idea of fun,” he said.