Rod MacVicar got the call late Thursday morning: ‘a group of killer whales is hunting up Indian Arm.’

This was no J-pod foraging for chinook salmon. These were transients, whales after red meat, and in the waters around Port Moody, that means harbour seals.

“They're like sticks of butter to them,” said Andrew Trites, local whale expert and director of the Marine Mammal Research Unit at Reed Point.

MacVicar — a former Coquitlam biology teacher, sea captain and local authority on anything ocean — digested the news the way a shepherd would upon the arrival of a pack of wolves. The four Steller Sea Lions at the research station had just become a buffet in a bottleneck for the incoming cetaceans, so MacVicar rang the alarm, calling up the trainers to get them out of the water.

“It's like the lifeguard that blows the whistle… ‘There's a shark in the area. Everybody out of the pool!’” said Trites. “We don’t want want to have our trained animals end up being lunch or dinner.”

Sea lions safe, MacVicar turned his attention to the spectacle at hand, one that had recently gathered rhythm up the Indian Arm as transient killer whales expand throughout the Salish Sea pursuig a healthy seal population. This was the third spotting of orcas in these waters in as many months, an unheard of set of appearances.

Rushing to the wharf at the Ioco Boat Club, I met MacVicar in the parking lot as he pulled up in a pickup truck.

We boarded Medusa, an aluminum hulled research skiff. Humming past the now quiet Burrard Thermal Generating Station, we rounded Racoon Island and drove deep up Indian Arm, where the cool waters of the inlet butt up against the foothills of the Coast Mountains.

Boats had already started to gather, some leaping into spots along the animals’ vector like a frog jumping from leaf to leaf. Canadian law requires boats get no closer than 200 metres when whale watching — a distance that will double to 400 metres in June — but several vessels in the area either ignored or were ignorant of that rule.

A high-speed coastguard boat flitted in and out amongst the sailboats, kayaks and motorboats — the officers lacking the authority to keep boats at bay.

A zoomed-in video of #orcas in Indian Arm. @Reynolds_JohnD @belcarradeb @DstrandbergTC pic.twitter.com/nAlMiZzx6K

— Ruth Foster (@SalmonRuth) May 23, 2019

By the time we arrived, the orcas had made their U-turn, and were headed back down the arm. With them came a Grady-White powerboat, motoring in their wake.

As they passed Buntzen Power House No 1, MacVicar took it upon himself to remind the whale stalkers of the law.

“You’re in violation of the…” MacVicar began before the captain of the other boat went on the offensive, firing back that the whales had just appeared off his bow.

The orcas kept hunting, the mother, Sydney, born in 1985 (a millennial?) with her 19-year-old son Stanley (named after Stanley Park), seven-year-old Lucky, and T-123D, whose existence was first confirmed last fall and is still without a name. Together with at least one other large male, they darted under water for long periods, sometimes producing 30-foot-wide patches of frothing bubbles from deep below, and never breaching. (Transient whales are known to remain silent when hunting to avoid tipping off their prey).

T123, as the family is known to researchers, has seen its share of tribulations; in 2011 — not long after her third offspring died — Sydney was stranded on a sand bar off Prince Rupert with her oldest son, Stanley, while chasing seals, according to Jane Cogan, a former Boeing engineer who now tracks transient orca families for the Center for Whale Research at Friday Harbor, Wa.

Cogan started by tracking southern resident orcas, but as they diminished in number, the transient, or Bigg’s killer whales, overtook her work.

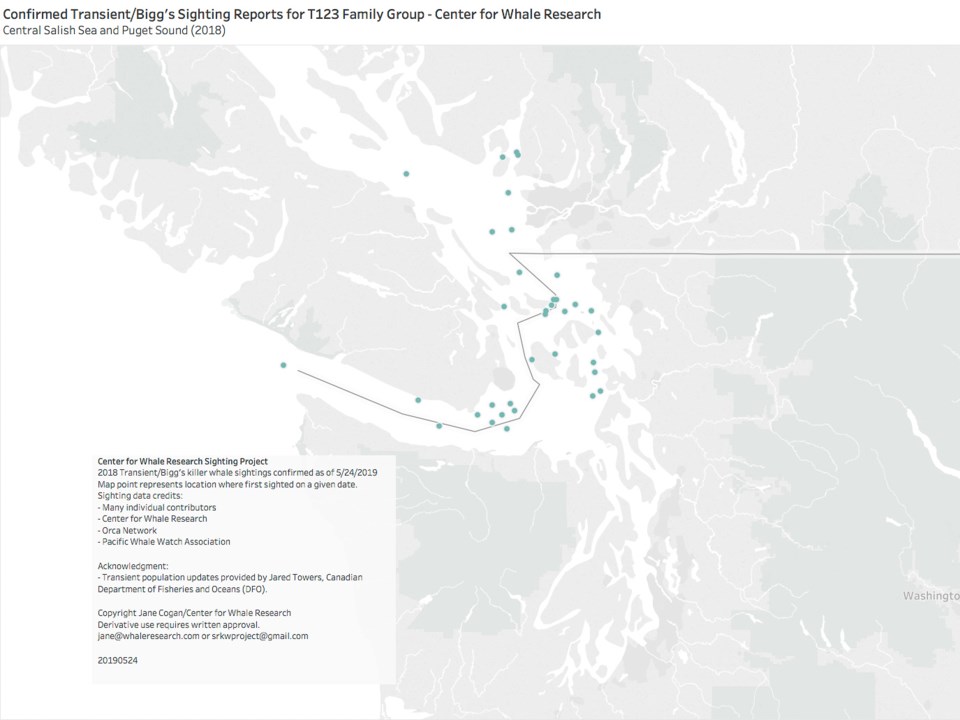

Today, she tallies and plots sightings of transient families only after they’ve been properly identified through photographs. And while that leaves the American researchers with an incomplete picture of the transients’ day-to-day habits, it also gives them a good sense of their movement.

Just last week, Sydney and her family were spotted northeast of Vancouver in Howe Sound, and a day later, off the west coast of Galiano Island.

“One day they’ll be by themselves, another day they’ll join up with a male or another group,” said Cogan.

The fact that this transient family is now plying the waters of the Indian Arm comes as no surprise to local whale researcher Andrew Trites, who noted the harbour seal population is strong and growing around Port Moody.

“It's been one of those well-kept secrets where the people of Port Moody know about it. But most of the killer whales don’t,” said Trites.

It only takes one animal to explore a fjord or inlet and light upon a large group of harbour seals, and the successive transient visits are a testament to increased natural abundance and hunter’s happenstance.

“They will remember that forever and come back, and perhaps bring other family members with them,” added Trites. “Port Moody is now on the tourist circuits of killer whales.”

Over the last 20 years, the harbour seal population has remained stable. What’s changed, according to Trites, is how they’re distributed. Where once they gathered in large groups, Trites is now finding evidence that they are scattered across the region, from Nanaimo all the way down to Puget Sound.

That’s natural behaviour for any potential prey species, said Trites. They’re simply trying to reduce the chance they’ll be found by the killer whales, and as a result, the transients are having an evening effect on the seals, causing them to pop up in places where humans, and in particular fishers, haven’t seen them for years.

That’s led some groups of sport and commercial fishers to call for a return of the cull banned on the West Coast since the 1970s.

“That would mean half of the transients will likely starve,” Trites said bluntly, confounded that people haven’t learned from their mistakes and that nature can balance itself.

It took over a century for whales to come back from the industrial slaughter that nearly extinguished several species and ‘re-wild the Salish Sea.’ Today’s numbers reflect a commitment to end the hunting of whales, but it’s also a product of a wider effort to protect the species upon which they feed — something that’s not as easily celebrated for the Bigg’s southern resident cousins who feed strictly on threatened salmon stocks.

To see Sydney and her entourage hunt in the vicinity of Canada’s third largest urban area is a sign things are going in the right direction.

“It is an urbanized wilderness,” said Trites. “We're living on the edge of the Serengeti — you can watch the real-life drama being played out as the predators are stocking the prey.”

“That's all new. And that is the re-wilding of our coastline.”