Asaad Al-Jaboubi left Yemen for love.

That was more than 15 years ago, not long after he’d met his soon-to-be Canadian wife, whose father had moved to the country to run a local university.

Landing in Toronto near the end of 2006, the young couple was soon headed west, drawn to British Columbia by its dramatic landscape and eventually settling in Port Moody.

“The mountains reminded me a lot of Yemen,” he said.

Over the years, he’d try to return home during the end of Ramadan to see his mother, father and siblings as they broke their fast and came together in celebration.

“It was beautiful how the country was developing,” he said of his early visits back to Yemen. “They had built better connections, better roads.”

The 2011 Arab Spring uprising brought a renewed sense of hope. But protests against government corruption and unemployment led to a violent police backlash as the government and Houthi rebel group vied for power.

When in 2015, the rebels seized the capital, Sana’a, declaring a “glorious revolution,” everything changed. Six years ago last week, Saudi Arabia launched Operation Decisive Storm, triggering what Al-Jaboubi says has felt like an endless war.

An accountant who had once started a newspaper in a bid to promote his homeland’s fledgling democracy, Al-Jaboubi found himself on the outside looking into what the United Nations describes as the world’s worst humanitarian disaster.

Soon, he’d learn Canada, his new adopted country, was supplying weapons to the same military dropping bombs on his hometown.

BOMBS START FALLING

From the beginning, the Saudi air campaign has blazed an indiscriminate path of civilian casualties.

In October 2015, one of Al-Jaboubi’s cousins was among upwards of 150 people killed in a horrific airstrike on a funeral that left more than 500 wounded.

“He was burned alive,” said the Port Moody man. “We couldn’t even recognize his body.”

Schools, hospitals and average peoples’ homes would soon fall in the line of fire as a sustained blockade on shipping led to widespread malnourishment. In December 2020, the United Nations estimated the conflict had led to 233,000 war dead, including 131,000 from indirect causes such as lack of food, health services and infrastructure.

Still, Al-Jaboubi would return at least once a year, bringing needed supplies and cash to his family as his Port Moody neighbours supported his wife while he was away.

“It’s very risky for her,” he said, pointing to the arduous four days it would take transiting through Egypt into Oman and the long road to his parents’ home in Sana’a.

“This road is still an active war. There’s bombings all the time. Sometimes you can wait for 10 hours, 20 hours, two days,” he said.

Passing from town to city, Al-Jaboubi says he still can’t shake the sense of resignation he saw in people with nowhere to go and nothing to eat.

“It’s like a ghost city. Basic food has become a luxury for people… I see my friends, I see my neighbours in the street begging,” he said. “Imagine you’re in the Tri-Cities and the bomb lands in North Van. They keep going.”

CAUGHT BETWEEN PANDEMIC AND WAR

During the six-year war, the community at the Al-Hidayah Mosque in Port Coquitlam and the Al-Ihsan Mosque in Port Moody have raised enough money to occasionally buy a few cows and feed up to 400 families at the end of Ramadan.

But as the war rages on the need has only grown, said Al-Jaboubi. A lack of clean water has sparked deadly cholera outbreaks, which combined with rampant malnutrition, has hit children the hardest.

When the COVID-19 outbreak arrived in the country, 80% of Yemen’s 30 million people were relying on food aid, many of whom already suffered from the pre-existing conditions that would make them vulnerable to the most severe cases of COVID-19.

Last summer, Al-Jaboubi said his friend, a doctor, worked through Ramadan only to catch the virus and slip into a coma. He died two months later, never waking up.

Caught between the risks of catching COVID-19 outside and the threat of airstrikes overhead, “People are scared,” he said.

CANADA ARMING THE AGGRESSORS

As Saudi Arabia continued its bombing campaign in Yemen, Canada has ramped up military exports to the country.

In 2019, Canada exported $4-billion worth of weapons overseas, the largest sum in its recent history. Of those exports, $2.8-million in arms — 76% of the total — went to Saudi Arabia, unseating the U.S. as the number one recipient of Canadian weapons, according to the organization Project Ploughshares, which among other things, tracks weapon exports around the world.

Most of those weapons are part of a $14-billion contract supplying Canadian-built light armoured vehicles (LAVs) to the Saudi regime. In 2019, Canada also sold 635 rifles and carbines, 31 large-calibre artillery systems, and 152 heavy machine guns, according to Ploughshares.

Several reports have placed those weapons at the front of the Saudi-led war effort.

After the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018, the Canadian government announced a freeze on exports to Saudi Arabia, but that did not apply to previously approved exports, and the ban was lifted in April 2020.

At the time, Canada’s then Minister of Foreign Affairs François-Philippe Champagne and Finance Minister Bill Morneau put out a statement saying that, as a party to the United Nations Arms Trade Treaty, Canadian goods can’t be exported where there is a “substantial risk” they would be used violate international law or human rights.

After reviewing the $14-billion arms deal to Saudi Arabia, the ministers added, “we have now begun reviewing permit applications on a case-by-case basis.”

Five months later, a September 2020 United Nations report into the war in Yemen found Canadian weapons were fuelling the conflict in contravention of international law.

A HUMANITARIAN STOP-GAP

Last month, Canada said it would commit $69.9 million to help humanitarian efforts in Yemen, its biggest promise of aid to the country since the war began, though a fraction of the billions of dollars in weapons the country has exported to Saudi Arabia in recent years.

While groups like Ploughshares have been quick to call out the government’s “moral deficit,” Al-Jaboubi says local representatives have also done little to heed a call to speak up: A letter to Port Moody-Coquitlam Conservative MP Nelly Shin three months ago went unanswered, he said.

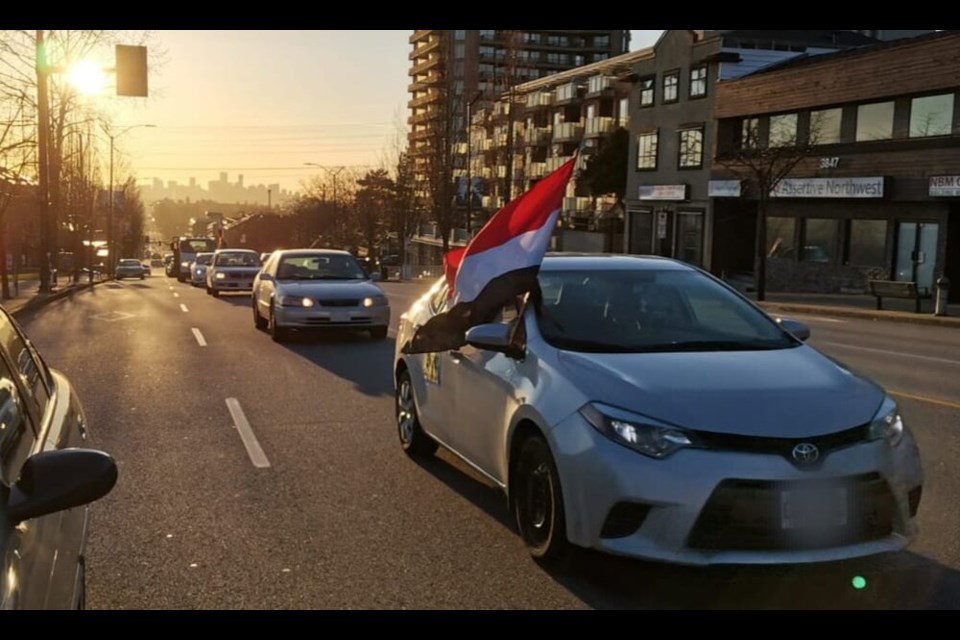

Still, Al-Jaboubi refuses to keep quiet. Every month, he leads rallies, debates and protest caravans throughout Metro Vancouver calling on Canada to stop selling weapons to Saudi Arabia.

“I’m contacting all the Imams in the mosques, contacting every Yemeni community in Canada,” he told the Tri-City News.

This week, Al-Jaboubi teamed up with Islamic Relief Canada to launch a fundraising campaign to raise $100,000 to back front line medical workers with equipment and supplies, distribute food aid and provide civilians with clean water, soap and education on how to stay safe during the pandemic.

“If Canadians knew what was happening in Yemen, they would be very angry,” said Al-Joubabi.

“Why do we have to gamble these people?”