The world's first computer programmer, Ada Lovelace, was born in 1815 to the poet Lord Byron and his wife. A highly imaginative young woman with a mind for numbers, Lovelace was the first person to suggest that computers could be used for things beyond simple calculations. Her theories, published in a scientific journal under a pen name, arguably altered the course of the modern world.

Since 2009, the second Tuesday in October has been recognized as Ada Lovelace Day. Aside from acknowledging the countess' work, the holiday also aims to celebrate the (often overlooked) contributions women have made in math, science, technology, and engineering. And believe us when we say there are plenty of them.

Here, Stacker looks at 10 groundbreaking inventions and the women who created them. From miracle medications to home security systems, these discoveries changed the world, and the brilliant minds behind them deserve to be celebrated much more regularly than they are.

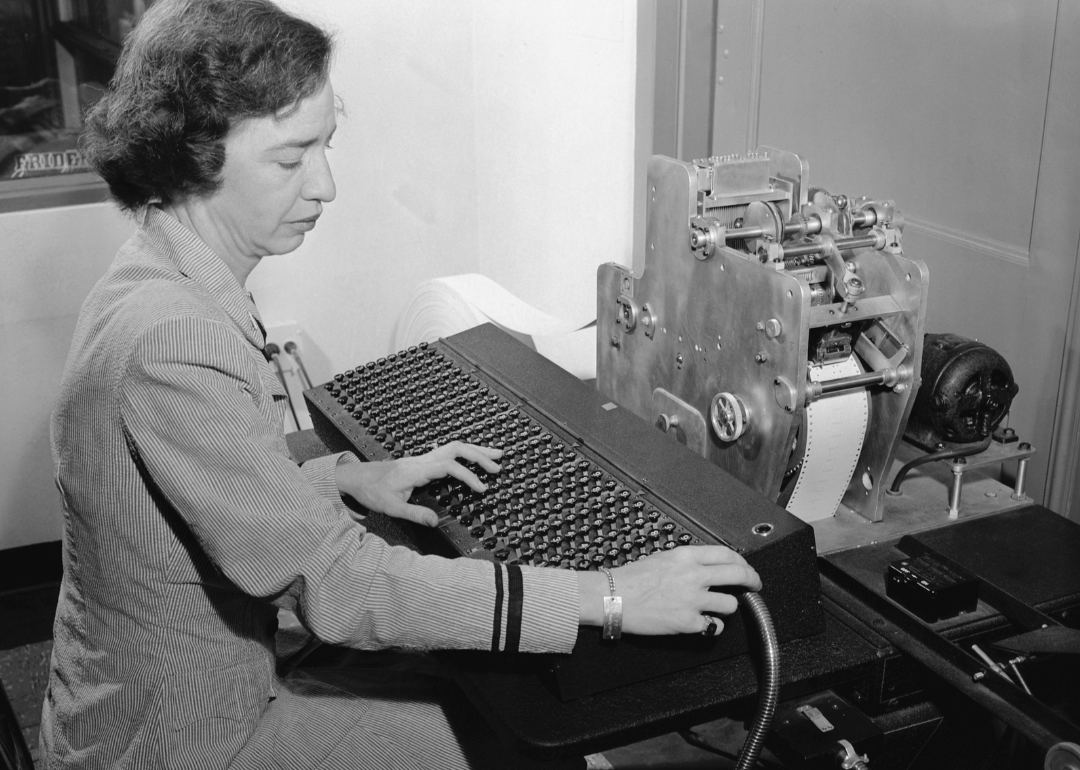

Grace Hopper

Grace Hopper was many things: a New Yorker, a naval officer, a mathematical genius, and a computer pioneer. During her time in the Navy, which began in 1943, Hopper was assigned to the team working on Mark I, the first electromechanical computer in the country. Using the knowledge she gained while a part of that project, she would go on to develop the world's first word-based computer code, FLOW-MATIC, and compiler, the A-0.

Her invention made computers more accessible to the average person, as most people were more comfortable using plain English than complex math problems to get the machines to do desired tasks. While she made her groundbreaking invention as a civilian, she would eventually re-enlist in the Navy to help develop computers and codes faster. She retired at 79 (at which point she was the oldest serving officer in the armed forces).

Marie Van Brittan Brown

The saying "necessity is the mother of all invention" could not ring more true for Marie Van Brittan Brown's creation, the modern home security system. As a nurse, she worked odd hours that often didn't align with her husband's shifts as an electrician; this meant she spent many nights alone in her Jamaica, Queens, apartment in New York. At the time, the neighbourhood had a high crime rate, and she felt unsafe sleeping there alone, so she worked with her husband to design a closed-circuit system that would allow her to see and speak to folks outside her home without ever having to open her front door.

She filed the patent for her system—which involved a series of peepholes, a moving camera, a two-way microphone, a remote lock and unlock device, and an alarm button—in 1966. The basic mechanics of her invention are the basis for every home security system or device (like the Ring doorbell) on the market today.

Evelyn Berezin

In the late '60s, Evelyn Berezin founded a tech startup on Long Island that would develop the first word processors. The computers, which allowed text to be edited as needed (versus typewriters that required you to start over every time you made a mistake) simplified work in dozens of industries and paved the way for word processing apps like Google Docs and Microsoft Word, which we all use today.

The word processor wasn't the New York native's only contribution to the tech industry. She also invented the first computerized airline reservation system in the late '50s. In her obituary, the New York Times quoted British writer Gwyn Headley, who wrote: "Without Ms. Berezin there would be no Bill Gates, no Steve Jobs, no internet, no word processors, no spreadsheets; nothing that remotely connects business with the 21st century."

Shirley Ann Jackson

A trailblazer in STEM, Shirley Ann Jackson is the first Black woman to earn a Ph.D. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. After graduation, she took her talents to AT&T Bell Laboratories, where her research in theoretical physics, solid state and quantum physics, and optical physics would lead to the development of caller ID, call waiting, fax machines, and touch-tone phones. Her discoveries have made life a little easier for all of us (in that we can now decide whether or not we want to hit answer on that phone call), but perhaps more importantly, her drive and focus on inclusion made it easier for minorities and women to enter STEM fields.

Jackson helped found the Black Student Union at MIT, as well as Project Interphase, a program that expands educational opportunities for minorities and widens the applicant pool for the university. She summed up her approach to life and science to ABC News this way: "It's about being able to walk so you can carry someone else. The more influential the positions I've had and the more powerful they've become, the more I've been able to help people develop open doors and help people step through. That is what's meaningful to me."

Ann Tsukamoto

It's not an exaggeration to say Ann Tsukamoto's work has saved the lives of millions. After graduating from the University of California, Los Angeles, the California-born scientist was part of the group that discovered human hematopoietic stem cells. She then co-patented a process to isolate these cells, which enabled scientists to use them to treat various cancers.

Until Tsukamoto's discovery and patent in the early '90s, it was widely believed that cancer in its various forms was an incurable disease, something we now know to be false. In recent decades, she's used her vast knowledge to help isolate and harness the power of liver and neural stem cells, allowing many to hope that other, equally devastating diseases may soon have a cure.

Patricia Bath

In the late '60s, after graduating from Howard University's medical program, an internship at Harlem Hospital, and a fellowship from Columbia University, Patricia Bath noticed a dramatic difference in the rates of blindness between Black and white people. Black people, she determined, were exhibiting blindness at nearly double the rate of their white counterparts. This, she was able to confirm, was due to a lack of ophthalmic care. So she proposed a new discipline, community ophthalmology, which is believed to have saved the sight of thousands of people worldwide who likely wouldn't have had access to eye care otherwise.

While inventing this entirely new type of medical care, Bath also patented the Laserphaco Probe, a surgical tool that vaporizes cataracts and allows new lenses to be inserted into a patient's eye, essentially restoring their vision. The device allows the surgery to be done quickly and more accurately without much of the risk that previous procedures would have included. The device has been used in countries worldwide since 2000.

Stephanie Kwolek

Stephanie Kwolek fell into chemistry almost by accident. Needing a steady paycheck to save up for medical school, she interviewed for—and landed—a role at the DuPont company. Initially placed on a polymer research project, her love for the work compelled her to stay.

A few years later, the talented scientist would be handed her own project: discovering and creating a selection of fibers capable of performing in extreme conditions. It was while working on this task that she developed Kevlar. Five times stronger than steel, Kevlar is used in bulletproof vests and undersea optical-fiber cables, among dozens of other things. Her invention would earn her the National Medal of Technology in 1996.

Katharine Burr Blodgett

In the early days of her career, Katharine Burr Blodgett helped develop a technique that allowed scientists to layer single, molecule-thick films on top of one another in collaboration with Irving Langmuir. It had applications in everything from solar energy panels to computer screens. It also creates 100% clear, nonreflective glass, ideal for eyeglasses, camera lenses, and telescopes.

Want an indicator of just how instrumental her discovery was? Watch "Gone with the Wind," the first film projected through a Blodgett lens, and compare it to any film that came beforehand. If her inventions don't convince you of her genius, perhaps the fact that she was the first woman to earn a Ph.D. in physics from the University of Cambridge and the first woman employed by General Electric will.

Hedy Lamarr

A woman of many talents, Hedy Lamarr was both an outstanding actress who starred in movies like "Samson and Delilah" and "The Female Animal" and a self-taught scientist who developed the technology that would eventually lead to Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and GPS.

At the start of World War II, Lamar, who had previously been married to an Austrian arms dealer, realized that new and inventive weapons and communications techniques would be needed to combat the Axis powers. Lamarr and collaborator George Antheil developed a frequency-hopping system that could be used to guide torpedoes. While her patent was taken under advisement by the Navy, they never actually used it during combat. It wasn't until much later that other scientists would use her work to develop things like Wi-Fi and Bluetooth.

Gertrude Belle Elion

The daughter of immigrants, Gertrude Belle Elion was inspired by the death of her grandfather and her fiance to pursue a career in science and medicine. A brilliant mind, she attended two New York City schools, Hunter College and New York University, before landing an assistant job at a pharmaceutical company. At this company, she worked with Dr. George Hitchings—a partnership lasting more than four decades. It was here that she developed three different drugs that would change the course of human history.

The first drug was the combination of medications given in modern-day chemotherapy for patients with leukemia (according to the American Chemical Society, this combination, along with maintenance therapy, has been responsible for curing 80% of children with leukemia). The second was an immunosuppressive drug that allowed critically ill patients to receive organ transplants without their bodies rejecting them. And the third, which would win her a Nobel Prize, was the world's first antiviral medication, often used to treat chicken pox and herpes.