Canadians living in low-income households will need $42 billion in government and public utility spending over the next 25 years to help retrofit their homes and escape “energy poverty,” a new report has found.

Modelling in the study, carried out by the energy think tank Pembina Institute, suggests federal and provincial spending on building retrofits would have to ramp up significantly to $2.8 billion a year starting in 2025 before finally dropping down by 2050.

The investments would help reduce energy costs and improve living conditions in old building stock not built for a rise in extreme heat, wildfire, smoke and flooding, said Jessica McIlroy, manager of buildings at the Pembina Institute and the report's lead author.

“If you have homeowners who are struggling to pay their energy bills, how are they going to afford energy retrofits?” McIlroy said in an interview.

“The pace and scale is just not there yet.”

The report leaned on national data that found the average Canadian household spends three per cent or less of their net income on energy. Those who spent six per cent, or more than double the average, on energy bills were defined as experiencing energy poverty.

The authors then refined those numbers using household economic data gathered as part of Canada’s national census. In the end, they found half of the 20 per cent of Canadians grappling with energy poverty in 2019 also fell into the low-income bracket.

Karen Tam Wu, an independent consultant and founding board member of Zero Emission Innovation Center, described the report as a “pretty robust” argument for financing a sustained retrofit economy that first targets Canadians who need it most.

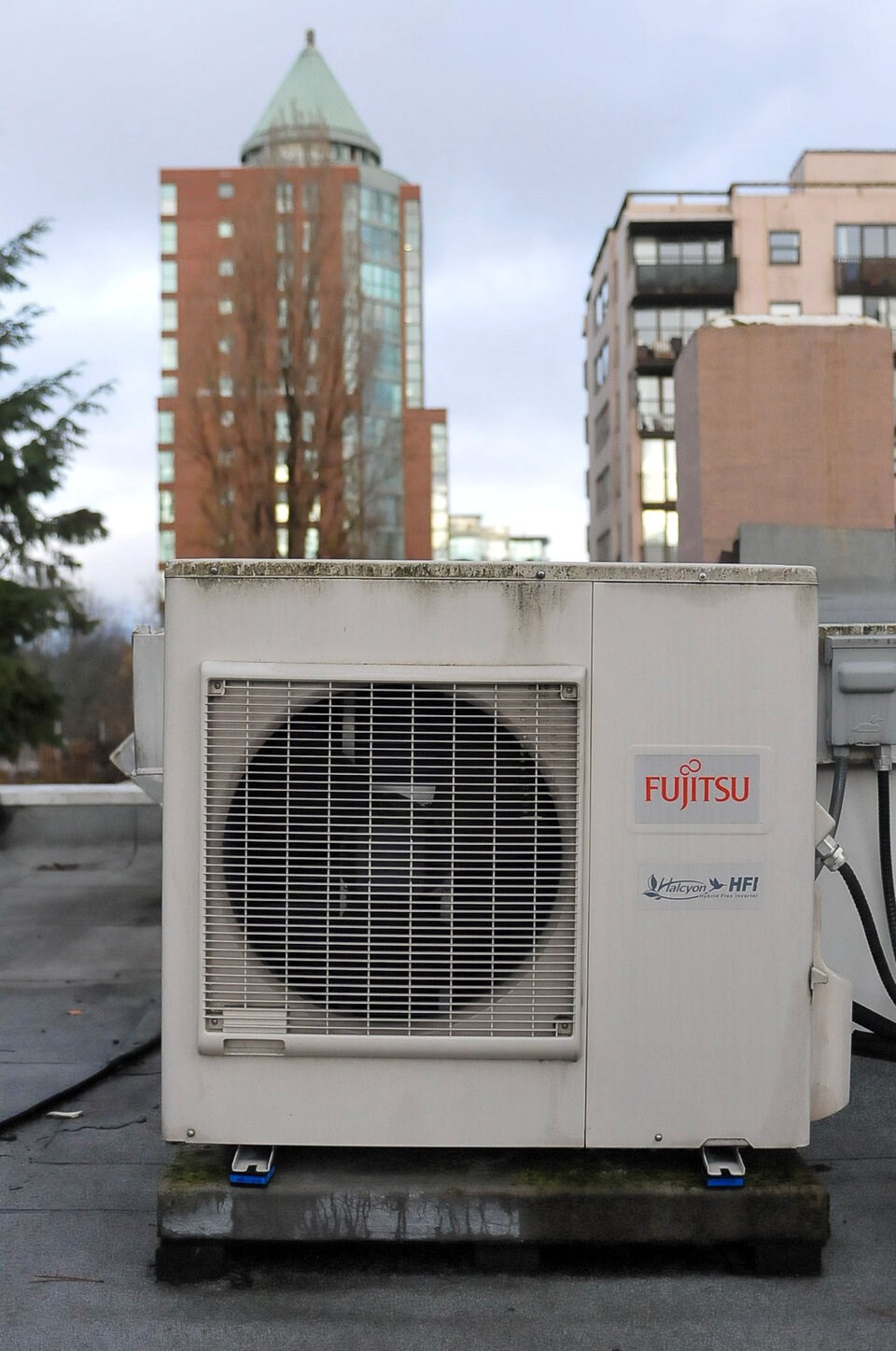

“Those are the households that are least likely to benefit from retrofits and things that higher income households can afford,” said Wu. “A heat pump provides very efficient heating, but it also provides cooling and we're seeing more and more of that being required as more Canadians are facing extreme heat events in the summer.”

“A heat pump is not as sexy as a Tesla, but certainly provides a lot of benefits.”

Kevin Lockhart, research manager at the think tank Efficiency Canada, also backed the conclusions in the report. He said reducing emissions will require retrofitting “almost every building in Canada” through retrofits and electrification.

Others, like Yasmin Abraham, co-founder and president of Kambo Energy Group, said the $42-billion retrofit price tag “does seem high” even for a relatively expensive jurisdiction like B.C.

A social enterprise that has spent 15 years targeting energy poverty across North America, Kambo helps low-income and marginalized people access green building retrofits funded by government, utilities and other organizations.

“We'll do windows and insulation and heating systems and air sealing and lighting, really with an effort to improve affordability in those homes,” said Abraham, whose organization has worked with 60 B.C. First Nations and retrofitted 7,000 low-income homes.

“I think that's really the high end of it,” Abraham added. “I am not saying that the dollar amount is too much… I just I think that we don't even need to spend that much money.”

Annual retrofit savings span $805 to $1,850 per household

In Canada, multiple levels of government have committed to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050, a point at which society absorbs as much carbon pollution as it emits. The target is meant to stave off some of the most catastrophic effects of climate change.

After oil and gas, the buildings sector is Canada's next largest source of emissions growth since 2005, a trend the Canadian Climate Institute warned last year is "undercutting" the country's progress in reaching its climate targets. And in many Canadian cities, inefficient buildings and gas-burning heating systems often account for more than half of all carbon pollution.

A previous report from Pembina found retrofitting all buildings across Canada would cost at least $10 to $15 billion a year over the next two decades.

The latest study focuses on a segment of those homes: at least 1.1 million households that are both struggling to make ends meet and don’t have the money to fix up their home and reduce their energy bills.

If carried out, the proposed building upgrades are expected to lead to hundreds of thousands of heat pump conversions and tens of thousands of retrofits per year. Together, the report says that would drop Canada’s greenhouse gases by 2.4 million tonnes, equivalent to eliminating emissions from 500,000 gas-powered vehicles.

At a household level, the average Canadian detached home would see annual savings of $1,850; an attached home $1,285; and an apartment $805, the report found.

According to Statistics Canada, that money couldn't come too soon. The national statistics agency found that by October 2023, one in seven Canadians resort to unsafe temperatures amid rising energy prices.

The survey also found more than a quarter of Canadian households reported not having an air conditioner or some other cooling equipment over the past year. That percentage spiked to more than a third for households with the lowest incomes, with those living in low-rise and high-rise apartments the most likely to be without AC.

In addition to easing the financial burden on the lowest income Canadian households, the Pembina modelling suggests the fully funded program would create 16,300 jobs and contribute $6.7 billion to the Canadian economy every year. That does not include additional returns through tax revenue and local economic growth, the authors said.

Despite the benefits, the $42 billion over 25 years would only help the most needy. Another 12.6 million more Canadian households were identified in the report as facing some level of cost burden when it came to paying their energy bills, but were not assessed to be the highest priority for government spending.

Retrofits a question of life or death

Investing in building efficiency is about more than reducing emissions and the cost of living, said McIlroy, who also serves as a city councillor for the City of North Vancouver.

By 2050, most Canadians will be living in buildings that are already built. But not all of them are thought to provide a safe refuge from extreme weather and the heat, wildfire, smoke, flooding and water damage that comes with it.

“We spend 80 to 90 per cent of our time indoors, and so we have to be able to adapt our buildings and make sure that we're still safe inside of them,” McIlroy said.

The Pembina report comes less than two months after health officials in British Columbia found Vancouver’s housing stock is contributing to a big gap in who faces the deadliest risks during extreme heat events.

The Vancouver Coastal Health Authority (VCH) analysis found that in a region housing 1.2 million people, 75 per cent of people living in homes without an air conditioner experience temperatures beyond 26 degrees Celsius — the threshold for increased risk.

Most of the 619 people who died during a record-shattering 2021 heat wave died in the Metro Vancouver region. Unlike other parts of the country where extreme heat is often a risk outdoors, in the Vancouver region, indoor air temperatures were found to be the biggest killer.

Heat-related visits to hospital emergency rooms were found to be highest in neighbourhoods where residents faced a combination of social isolation, advanced age, preexisting health conditions, substance use, a lack of green spaces, and poverty.

A scientific investigation into the 2021 extreme heat found it was made 150 times more likely due to climate change. By 2040, the rapid attribution study anticipated the region could experience similar heat waves every five to 10 years. All the more reason to prepare now, according to the Pembina report.

But Abraham warned targeting low-income homes is not always easy. Just like people who access food banks, she said it takes a lot of time to build trust within communities to the point where people let you into their home and private lives. Unlike food banks, there’s nowhere to go when you can’t pay your energy bill.

“It really is a hidden problem. And there's definitely an embarrassment and the shame,” Abraham said.

“Lots of people are like just turning off their heat entirely and maybe just heating one of their rooms, maybe their kid's room with an electric heater, which is fine, but it's you know, it can be dangerous. We see lots of really awful situations.”

Federal government should pay half, say authors

The Pembina report suggests half of the $42 billion in retrofit money should come from the federal government, one quarter from the provinces, and final quarter from utilities.

The money would support building envelope upgrades, like new insulation and windows, as well as replacing gas heaters with electric heat pumps — an often more efficient technology that heats and cools homes with a fraction of the carbon footprint. Ideally, McIlroy said retrofits would also help reduce electricity consumption and lower bills from the supply and demand side.

At the moment, however, the building expert and city councillor says the speed and scale with which Canada and B.C. are moving remains far off track their own emission reduction targets.

“We can see that because we're not meeting the CleanBC target,” McIlroy said. “I know people personally who are now moving because they're trying to get away from wildfire smoke.”

“We are losing lives, right? That is enough for me to say that this is warranted.”