A man convicted in the May 2005 Vancouver death of an Afghan pop star will plead guilty to criminal harassment.

Ahmad Seiar Froogh, 36, appeared before Vancouver provincial court Judge Reginald Harris on Nov. 22. He's charged with criminal harassment and breach of a release order.

The charges stem from a March 25 incident where the woman involved feared for her safety, court records show. The breach order relates to a non-contact order regarding the alleged victim.

Crown prosecutor Rosanne Sinclair told Harris there is a psychiatric component to the case, which has been put over to Dec. 6. The judge said the pleas would need to be taken.

Froogh’s lawyer, Rishi Gill, confirmed to Glacier Media there is a mental health component to the case.

“The justice system is not the place for mental health cases,” Gill said, noting he was not Froogh’s lawyer at the time of the conviction in pop star Nasrat Parsa’s death.

Pop singer's death

Froogh, then 22, was convicted of manslaughter in the death of the Afghan pop singer and sentenced Feb. 20, 2009 to house arrest and probation.

B.C. Supreme Court Judge Geoffrey Gaul said Froogh, who pleaded guilty to the charge, was being punished for committing a dangerous act, not for Parsa’s killing.

Gaul ordered Froogh, originally from Afghanistan, to serve two years of house arrest and three years of probation.

The court heard that Froogh and some friends followed Parsa to his Kingsway hotel to get an autograph after they had attended his concert at Vancouver's Queen Elizabeth Theatre.

Froogh approached the 35-year-old Parsa and suddenly punched him. The court heard the singer suffered facial bruising. However, Parsa fell down a flight of stairs and died four days later of a brain injury.

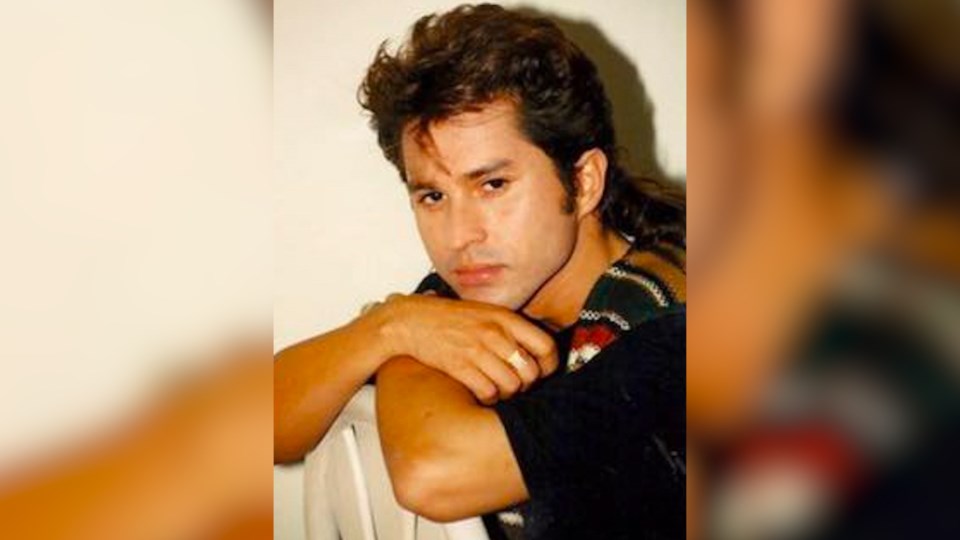

Parsa was considered one of Afghanistan’s most popular singers. He left Kabul as a 12-year-old prodigy; he went on to study music in India before settling in Germany.

Parsa had released a total of 10 albums.

Immigration matters

On Nov. 30, 2010, the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada appeal division rejected Froogh’s appeal of a Jan. 29, 2010 removal-from-Canada order.

He was then 24 and a citizen of Afghanistan.

The decision said he was a "convention refugee" and a permanent resident who landed in Canada on Nov. 29, 2001.

The federal government defines a convention refugee as someone outside their home country or the country they normally live in and unable to return due to fear of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinion.

Froogh testified about the manslaughter conviction at the immigration hearing.

“The appellant testified that he was saddened by the events but he denied any responsibility for the incident,” the decision said. “The appellant indicated he had been drinking before the incident and that they only wanted to get an autograph from the victim but it was refused. The appellant maintained that he did not see what occurred as he had been pushed to the ground and he was told to run away and that is what he did.”

Gaul said the punch to Parsa “was a dangerous act and a significant contributing factor to Mr. Parsa’s death. But for the punch, Nasrat Parsa would not have fallen, would not have struck his head and would not have suffered his fatal injuries.”

In the immigration case, Froogh did not contest the legality of the removal order. Rather, he contested the underlying criminal conviction.

“The panel is not prepared to go behind the findings of fact of the court in this matter,” board tribunal member Kashi Mattu said. “The appellant has not started on the path to rehabilitation as he does not accept any responsibility for his actions but rather denies all responsibility for the incident and the fatal consequences.”

The decision did note there had been a temporary suspension of removals to Afghanistan.