In the past year, hundreds of people have walked through the doors of Substance, a free and confidential drug-checking service in Victoria’s North Park neighbourhood.

More than 2,500 drug samples have been tested for fentanyl, contaminants or cutting agents at the modest storefront service run by the University of Victoria.

The storefront location, which marked its one-year anniversary this week, shows it’s an open place to talk about substances, provide information and answer questions, said Bruce Wallace, a scientist with the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research and associate professor with UVic’s School of Social Work.

“I think it’s really welcoming for the really diverse communities of people who either use drugs or care for people who use drugs and want to have as much information as possible.”

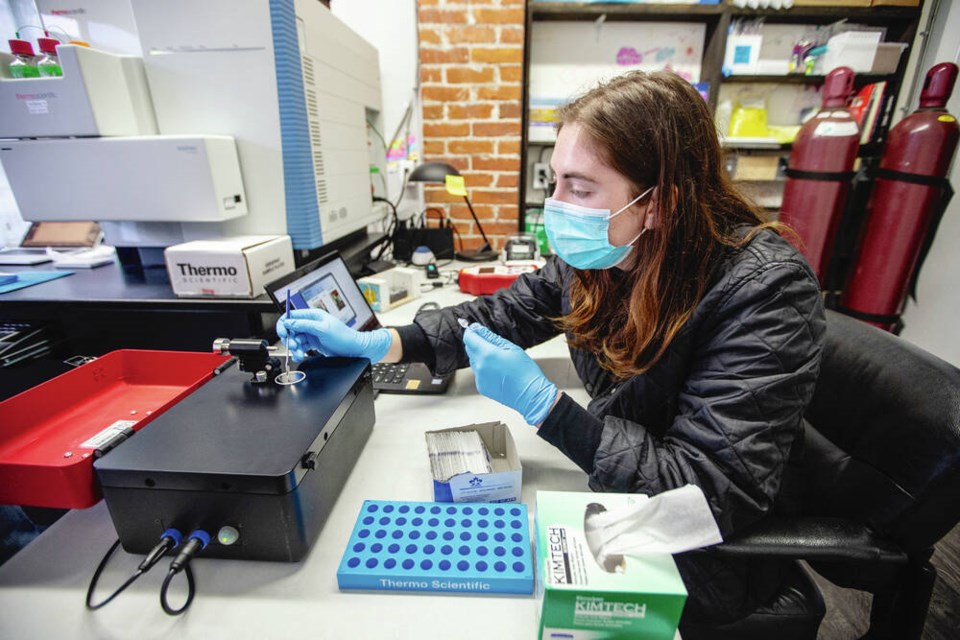

Drug samples are tested with fentanyl strips, plus four different spectrometers, which can identify the main drug and the amount of it in the sample compared to other ingredients. It can also identify contaminants or unexpected drugs, cutting agents and fentanyl or fentanyl analogues.

The goal is not to tell people if the drugs are safe or unsafe for use, said Abby Hutchison, a UVic graduate student in public health and social policy and Substance employee.

“People can make informed decisions about the substances they use. Most of the time, folks have a good idea of what works for them and what they are comfortable with, so they can take that information and it informs how they will use it,” she said.

Over the past year, she has noticed that the illicit opiate supply is very volatile and changes all the time.

“That’s where we see the most variants,” said Hutchison. “Sometimes the samples have very low concentrations. Sometimes, there can be high concentrations. Sometimes, there are other substances like benzos [benzodiazepines] in them and different cutting agents.”

Recently, Substance has found a lot of benzodiazepines — depressants often prescribed for anxiety and insomnia — in the fentanyl samples. Technician Becca Louw said the most common one they see is etizolam. “It puts people out for a really long time. It can sometimes complicate overdoses, so we try to let people know if they have it so they can make an informed decision.”

Both Hutchison and Louw were surprised to find that the whole illicit drug supply is not contaminated — methamphetamine, cocaine and MDMA are often exactly as they are sold.

“The methamphetamine and cocaine we see is actually uncut, so that was reassuring,” said Louw.

That said, last week they found three samples of cocaine that contained fentanyl, an extremely rare occurrence.

People come in before they socialize and share their drugs with friends. Sometimes, drug sellers want to check the quality of their supply. Friends and family members bring drugs in for those they care about. Outreach workers bring them in for their clients. “We’ve been really busy for the last couple of months,” said Hutchison.

The service publishes weekly and monthly reports of what it has found — for example, what percentage of opioid samples contained fentanyl, and how concentrated it was. It has an online presence for people who don’t want to reveal their substance use (substance.uvic.ca), and allows samples to be mailed in for testing.

Drug-checking helps control the market and holds everyone accountable, said Fred Cameron, program director for SOLID, a Victoria organization of current or former illicit drug users.

“We’ve made our direct community a lot safer,” said Cameron. “This on its own is not going to fix the problem, but it’s woven into the fabric of the community.”

Wallace and chemist Dennis Hore, an expert on drug-checking methods and technologies, are trying to figure out the different ways to reach people who are hiding their drug use.

“We know that hiding substance use and the stigma around substance use is a really significant part of this,” he said.

They are hoping to move the drug-checking models to other communities, including Port Alberni next month, then Campbell River. The goal is for harm-reduction workers in overdose-prevention sites to basically run a sample, which can then be analyzed in Victoria.