The head chief of an Island First Nation has filed a civil claim against the province on behalf of his people for aboriginal title to about 430,000 hectares of land in the Gold River-Tahsis area.

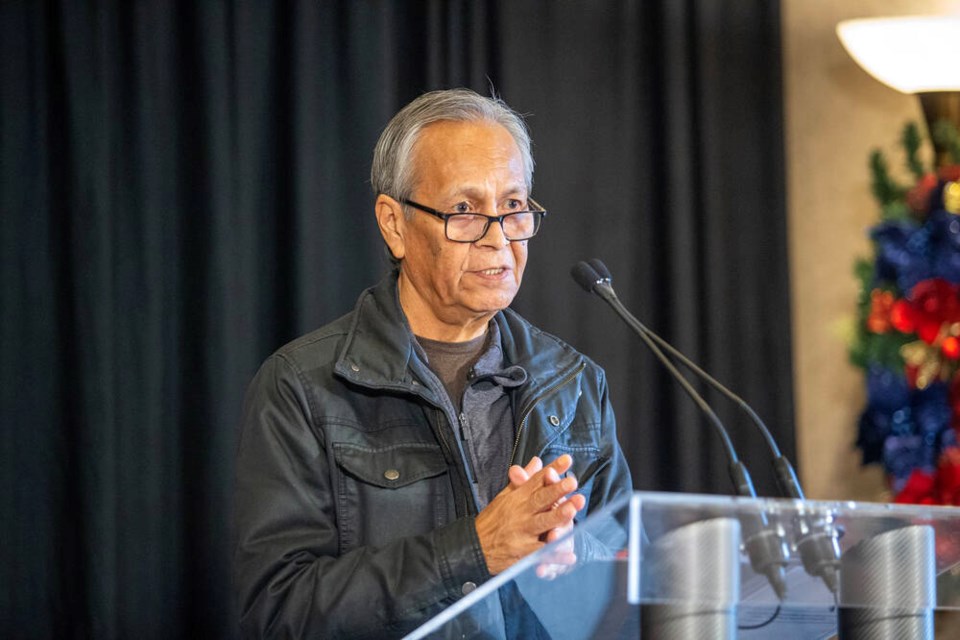

Mike Maquinna of Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation is also asking for monetary compensation for forestry operations on the nation’s traditional lands.

Maquinna said at a news conference in Victoria on Thursday that his ancestors met Capt. James Cook, the first European known to have set foot on what is now known as Vancouver Island, at Friendly Cove — known as Yuquot — in Nootka Sound in 1778.

“Our people, the Mowachaht/Muchalaht, have endured many hardships since first meeting Captain Cook,” he said. “The natural resources of our people, of our lands, have been taken.”

No one asked permission, and none was granted, and it’s time to correct some of those wrongs, he said.

Maquinna said since European contact, his people were forcibly relocated twice to different reserves. The Mowachaht and Muchalaht peoples were amalgamated into one nation in 1951 that was known as the Nootka Indian Band prior to 1994.

The claim filed by lawyers with Woodward & Co. in B.C. Supreme Court on behalf of Maquinna seeks aboriginal title over about 430,000 hectares of lands and waters between Tahsis, Yuquot and Buttle Lake, as well as monetary compensation from the revenues generated by provincially approved forestry operations and other damages.

At an unrelated news conference in Langley, Premier David Eby said the B.C. government prefers negotiated land-claims settlements to lengthy, expensive court cases, but the Mowachaht/Muchalaht have the right to take that route.

“We have no problem with them doing that,” he said. “We’d rather sit down and find a path forward.”

Maquinna, who is representing the Mowachaht/Muchalaht peoples in the suit, is also seeking to return forestry and environmental decision-making rights to First Nation hands.

Logging and other industrial activity has had “devastating” effects on the ecosystems on their lands, he said.

“We feel that we need to step in and make sure that our way of life, and those that are within our territories, are protected.”

The Gold River-Tahsis region had been a logging hub on the Island for decades, drawing workers from across Canada before the mills in the areas closed down.

The Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation estimates “millions” of cubic metres of timber have been removed from its lands since the early 1990s, with others reaping most of the profits.

Maquinna said the nation hopes to bring more sustainable and diversified jobs into the region rather than relying on a single industry.

The Ministry of Forests referred questions about logging practices in the area to the Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation, which declined to comment, saying the case is before the courts.

Western Forest Products Inc. currently holds the two major tree farm licences in the area claimed by Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation, which are set to expire in 2027.

Hereditary Chief Jerry Jack Jr. said he was shocked by how much his land had been changed by logging when he flew over with the Canadian Coast Guard a few years ago. “I couldn’t believe how much of our territory was gone. No more forest,” he said at the news conference.

Jack said the land title court case was decades in the making, noting his nation dropped out of formal treaty talks with the federal and provincial governments in the early 2000s.

“We realized that we were not going to get recognition and we were not going to get the federal rights to our territories. They were only going to give us bits and pieces like what we have now,” he said.

“We’ve been putting this together forever, and we’ve learned from other cases.”

Evidence of his nation’s long-time occupation of the area can still be seen in the trees, some of which still bear the scars of when people used to stripped off the bark and wood for creation of goods such as baskets and hats, Jack said.

Brian Thom, a University of Victoria anthropology professor who specializes in Aboriginal title rights, said neighbouring Nuchatlaht First Nation, whose territories border Mowachaht/Muchalaht on Nootka Island and Vancouver Island, made a similar argument with their recent aboriginal title claim case.

A B.C. Supreme Court ruling in April gave the Nuchatlaht title to about 11 square kilometres of land on Nootka Island, an area about the size of Oak Bay and “a far cry” from the 201 square kilometres claimed by the nation, Thom said.

The ruling is currently being appealed by the Nuchatlaht.

Thom said title cases in B.C. Supreme Court can be risky and expensive — one launched by the Tsilhqot’in Nation saw five years of court hearings and cost the nation $30 million in legal fees. “That’s just for one party. We don’t really know how much the Crown is spending on these cases,” he said. “Win or lose, the stakes are high.”

But Thom, who was involved in Hul’q’umi’num Treaty Group negotiations from 2000 to 2010, said some nations prefer to go to court over the “tortuously slow federal and provincial decision-making processes at the treaty table.”

Mowachaht/Muchalaht’s land title case does not make claims against private landowners, homeowners or recreational hunting and fishing operators.

Jack said homeowners in Tahsis and Gold River “have nothing to worry about.” “We’re only seeking relief from against the province,” he said.

Mowachaht/Muchalaht’s land claim overlaps with claims from other nations in the area. Jack said his nation is already in talks with two of its neighbours about the overlap and doesn’t foresee any problems, adding Nuu-Chah-Nulth Tribal Council president Judith Sayers has pledged her support for the claim.

— with a file from the Canadian Press